“The actual shoreline is among the most uncertain contours found in nature.” This line, from an 1880 report by government hydrographer Henry Mitchell (1830–1902), expresses the elusive status of the water’s edge in the 19th-century United States. As a member of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, founded in 1807 as the nation’s first governmental scientific agency, Mitchell’s job was to help produce the most accurate charts of America’s fluctuating coasts. Unlike arbitrary boundaries imposed upon otherwise contiguous spaces, shorelines were and are easily “found in nature.” Yet mapping them meant accounting for their ever-changing shapes, fluctuating tides and weather, and less visible shoals and depressions beneath the water’s surface—features and conditions that troubled the certitude that navigational data and cartographic symbols were supposed to provide. The word contour evokes both the graphic and topographic implications of this challenge: if shorelines were fundamentally uncertain, then surveyors faced the paradoxical task of representing terrains that, by their very nature, resisted the modes of delineation necessary to translate them into two-dimensional visual form. What, then, did it mean to delineate such an “uncertain contour”? And what does such a project reveal about the historical stakes, and limits, of visual and territorial knowledge at the confluence of ocean and land?

These questions motivate my dissertation, which I am completing at the Center. Examining paintings, printed maps, drawings, technical manuals, and scientific illustrations, I investigate how the problems of observing and representing coastal terrains tested prevailing understandings of the relationship between vision and epistemology across aesthetic, scientific, and technological spheres of production whose historical interconnections challenge present-day disciplinary divisions. This project uncovers the surprisingly uncertain relationship between seeing and knowing that shaped how terraqueous spaces were mapped, pictured, and imagined in a period of imperial and colonial expansion, technological modernization, and proliferating modes of transoceanic exchange.

In the words of a period commentator, throughout the latter half of the 19th century, “the American people have had their attention directed largely to the sea coast.” Accompanying this coastward turn, the conditions precipitating the shore’s uncertainty became newly visible—and visible in unprecedented fashion—across art, science, and politics. Within the fine arts, the flux of waves and tides and the effects of coastal atmosphere and topography featured prominently in so-called “water-scapes,” “coast-scenes,” “water-views,” and “shore-scapes,” creative descriptors that anticipate today’s “seascape,” then rarely used. Among the artists who became increasingly interested in coastal subject matter, some were particularly drawn to the shore’s challenges to empirical observation and mimetic representation, which were discussed across period literature, art criticism, and natural history. My research examines how these challenges led artists such as Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), William Trost Richards (1833–1905), and Edward Moran (1829–1901) to rethink, and even subvert, the techniques and ideologies that underpinned conventions of pictorial realism and “truth to nature” in painting, drawing, and watercolor.

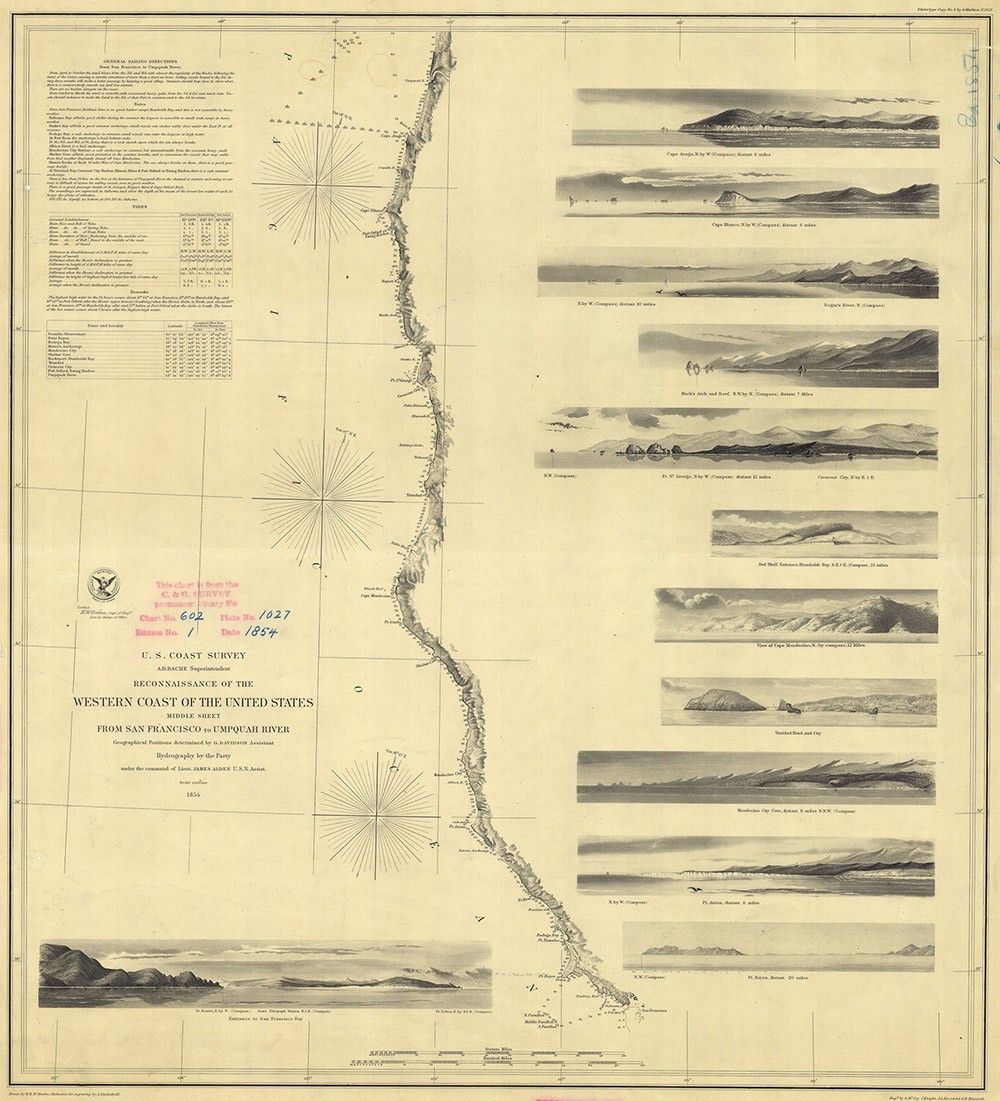

During this period, the coasts’ visibility and graphic presence also became strategically and scientifically important amid the United States’ growing colonial and imperial ambitions. Coast Survey cartographers, draftsmen, and engravers strove to incorporate a widening swath of lands and waters, including those of the newly annexed Pacific coast, into a standardized body of visual knowledge, aiding ongoing processes of settler-colonial expansion and the dispossession of Indigenous polities. Yet as I demonstrate, the coast’s persistent challenges to observation and delineation also frequently thwarted Coast Survey mapmakers’ capacity to assert either scientific accuracy or spatial authority, complicating the relations between geographic knowledge and territorial domination that typically contour historical narratives of US expansion. Meantime, a transatlantic cohort of artists, entrepreneurs, and naval scientists sought to scrutinize the deepest reaches of the ocean in order to render them accessible to new forms of incursion, such as the laying of the first transatlantic submarine telegraph cables. The visual products of such efforts to “see” underwater, I argue, reveal how the coast became both an epistemological threshold and a misleading vantage point that informed period conceptions of undersea geography, ocean science, and the subaqueous dimensions of empire on and between the edges of the Atlantic.

The coastal images, practices, and objects I examine in my dissertation offer new ways of contextualizing, and unsettling, visual histories of 19th-century landscape and geography by approaching them from a saltwater perspective that troubles deterministic and teleological definitions of “American” space and identity. Brought together, they reveal how new forms of skepticism toward vision and related concepts of truth, realism, and illusion—long considered signposts of emerging modes of visual modernity within the long 19th century—took on distinctive epistemological, pictorial, and spatial stakes alongshore.

[Princeton University]

Wyeth Fellow, 2019–2021

In spring 2021, Kimia Shahi will begin an appointment as assistant professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Southern California. Beginning in fall 2021 and continuing through spring 2023, Shahi will also hold a postdoctoral fellowship at the Harvard University Center for the Environment.