Ellen Tani

Black Conceptual Practice, 1970–1985

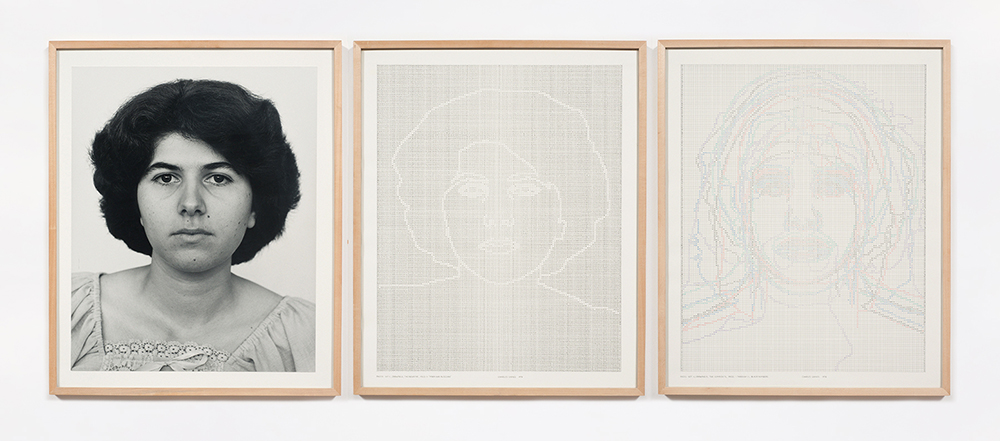

Charles Gaines, Faces: Set #11, Mary Ann Aloojian, gelatin silver print and ink on paper, 1978, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Dian Woodner in honor of Dr. Stuart W. Lewis and The Friends of Education of The Museum of Modern Art © 2021 Charles Gaines

In the mid-1970s, conceptual artist Charles Gaines (b. 1944) began making what he called “gridwork”: photographs of living objects (plants or humans) and hand-drawn grids filled with numerical translations of the photographic form. An exemplary case of systems art and photoconceptualism, Gaines enjoyed the support of major galleries in New York as well as early institutional appreciation from universities and museums. Yet, as an African American, he was called out by his Black and white peers for making “white art,” raising questions about the seeming incommensurability of avant-garde practice and identity politics that unexpectedly manifest in a range of artistic strategies found in Black conceptual practice from 1970 to 1985, the subject of my book project.

Conceptual art offered a way for Gaines and others to critique the institution of art while still participating in it, reflecting the tumultuous era from which the art world emerged in the late 1960s. In my book, I examine how Black artists deployed conceptual strategies—appropriation, language, systems—to negotiate the unique structures of constraint and opportunity that shaped artistic positionality for African American artists in the 1970s and 1980s. Gaines, Adrian Piper, Senga Nengudi, Lorraine O’Grady, and David Hammons share a historical foundation with first-generation conceptual art on the East and West Coasts. Their work offered a crucial model for a later generation of artists, such as Lorna Simpson and Glenn Ligon, who in turn advanced a conceptual critique of politics and ideology in the 1980s through photography, performance, intermedia, and installation. While Gaines and Piper successfully accessed the mainstream New York art world, Nengudi and Hammons—who shared a studio in Los Angeles for a period—exhibited on its margins at Just Above Midtown, the first gallery in New York dedicated to experimental African American art practices, founded by curator Linda Goode Bryant in 1974.

I spent the fall of 2020 completing research and writing on Nengudi, and I dedicated the winter to developing my first book chapter on Gaines’s gridwork. Gaines, an acclaimed artist and cherished professor, remains beyond the grasp of major survey texts on both 20th-century African American art and conceptual art, highlighting an aporia within art history, which has historically resisted situating conceptual practices by African American artists within contemporary art. Gaines exhibited his work toward the end of conceptual art’s flourishing and within a period where the market for African American artists, shaped by the widespread influence of the Black Arts Movement (c. 1965–1975), demanded a certain aesthetically legible “Blackness.” Though these factors contributed to Gaines’s art-historical eclipse, his gridwork laid the foundation for a commitment to systems and their interrogation that has spanned half a century. Gaines did not share with conceptual artists a strong motivation to solely redefine or explore art, either through the use of systems or otherwise. Within the artistic pluralism of the 1970s, he embraced wide-ranging influences, from tantric art to Henri Focillon to John Cage, whose common denominator was a departure from Western cultural norms of knowledge, history, and order. Able to both grasp conceptual art as a historical object and use it as a tool, Gaines offers a unique case study in how conceptual art shaped contemporary African American art practice as an adjacent mode to figural representation.

As this year draws to a close, I am awaiting the publication of Transnational Perspectives on Feminism and Art, 1960–1985, edited by Jen Kennedy, Trista E. Mallory, and Angelique Szymanek. I contributed the chapter “‘Really African, and Really Kabuki Too’: Afro-Asian Possibility in the Work of Senga Nengudi,” which explores the impact of contemporary and traditional Japanese art on Nengudi’s conceptual practice, looking in particular at the year she spent in Japan at age 20. While Black artists’ engagement with African Diasporic cultures is well-documented, their meaningful connections with other non-Western cultures—specifically those of Asia—has remained under-explored in art-historical scholarship.

With support from the Center, the Clark Art Institute, and the Getty Research Institute Library, I will spend the summer continuing my archival and secondary research on O’Grady, who directed conceptual art’s legacies in performance and its ideological critique toward the perceived complacency of a segregated and essentializing art world in the 1980s.

A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, 2020–2022

Having spent the first year of her fellowship writing about Gaines and the foundational terms of her book project, Ellen Tani will focus more exclusively on the work of O’Grady during the second year. She will also teach a course at Howard University.