Explore the Basics of Photography

Digital camera photographs

When you take a photograph with a digital camera, you press a button that briefly opens a shutter. This allows light to travel through a lens made of glass or plastic. The lens focuses the light onto a sensor inside the camera. To allow the desired amount of light to reach the sensor, you can adjust how quickly the shutter opens and closes as well as how wide it opens (the aperture size). The sensor converts the light into a digital photograph via a computer chip and then stores the photo on the device’s memory card as a digital image file. A high-definition (HD) photograph is composed of thousands of pixels that can be enlarged (by zooming in) without losing detail or becoming blurry. Cell phone cameras work in a similar way to professional digital cameras.

Digital image pixels

Gelatin silver print - silver grains

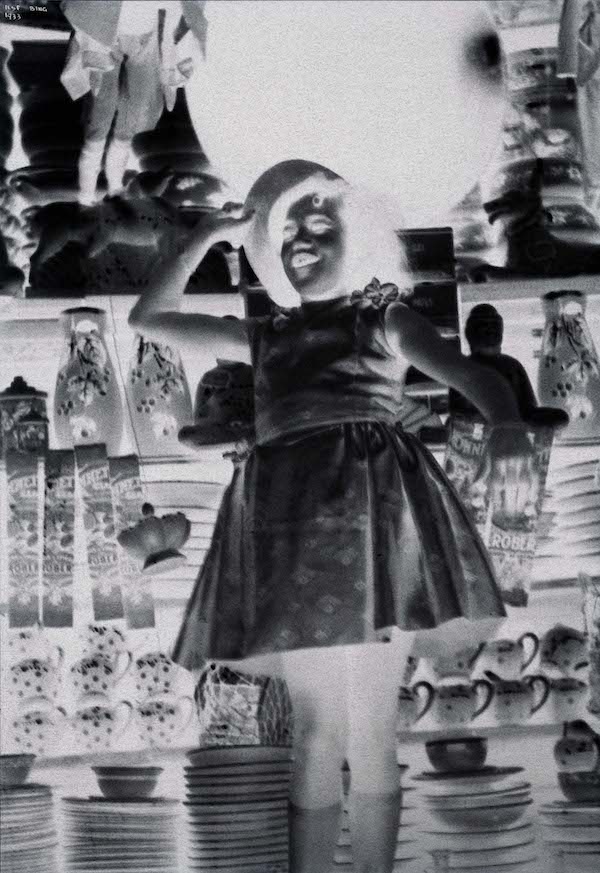

Traditional camera photographs

Traditional cameras operate much like digital cameras, using lenses, shutters, and apertures to focus the image and to control the amount of light that passes through the lens. The sensor in this type of camera, however, is a plastic strip of film coated with microscopic silver particles. Light turns the silver particles dark. Black and white tones are reversed, or “negative,” on the exposed film. (See the example of the girl.)

Before the film is placed in the back of the camera, the strip is tightly wound and stored inside a small canister to keep the film away from light. After the film is properly loaded inside the closed camera, the photographer advances the film after each photo is taken. This prevents the negative images from overlapping and creating a double exposure. Most film strips have space for 24 or 36 images. When the entire roll of film has been exposed, the photographer rewinds it and returns it to the canister.

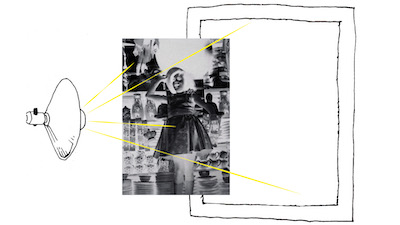

In the darkroom, the photographer unwinds the film and immerses it in a series of chemical solutions, or “baths,” to ensure the silver particles no longer react to light. The photographer uses the negative to “print” a positive photograph onto papers that have been coated with microscopic silver particles, which react to light just like the particles in the film. Shining light through a negative onto the photograph paper reverses the tones in the image, producing a positive photograph. The papers are then “developed” by immersing them in special chemical solutions, just as was done with the negative film (see illustration). The photographer can alter the image by making areas darker or lighter, or by cropping and blocking out areas.

Subject

Negative

Photographer Ilse Bing produced her gelatin silver print on paper that was specially prepared with a layer of silver particles suspended in a gelatin binder, which holds the particles onto the paper support. The silver particles react when light is directed through the film negative. Lighter areas allow more light to pass through the negative, which creates darker areas on the paper. Darker areas of the negative stop the light, resulting in lighter tones in the black-and-white print. Immersing the paper in a series of chemical baths completes the process of “fixing” a permanent photographic print.

Exposure

Developing

Diagrams courtesy of Veronica Diaz-Mendez, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow, Photograph and Preventive Conservation