The Life of Animals in Japanese Art

Unknown artist, Haniwa Horse, Kofun period, 6th century, earthenware, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of the David Bohnett Foundation, Lynda and Stewart Resnick, Camilla Chandler Frost, Victoria Jackson and William Guthy, and Laurie and Bill Benenson

Kannon is the Buddhist deity of compassion and mercy. Here, the sculpted horse on his head signifies that he is also a protector of animals and those reborn in the animal realm. With three eyes, three heads, and six arms, this Kannon is all-seeing, all-knowing, and ready to rush to the aid of any creature needing his protection. His fierce expression signifies his ability to conquer all evils. Made a thousand years ago, it is the oldest-known wooden sculpture of this deity in Japan.

Unknown Artist, Seated Horse‑Headed Kannon, Heian period, 11th century, wood, Yamakado Jichikai

Here monkeys sporting the tall hats favored by the nobility take part in a race; one monkey has apparently fallen off the runaway deer and is consoled by a rabbit and another monkey. This scene was detached at an unknown date from a set of handscrolls featuring caricatures of animals endowed with human traits. The scrolls’ purpose is a mystery, as no texts accompany the images. They may be the first use of animals to satirize contemporary society, or even the ancestor of modern Japanese manga comics. The handscrolls are preserved at Kozanji, a Buddhist temple near Kyoto, and designated a National Treasure by the Japanese government.

Unknown artist, Monkeys, from the handscroll Frolicking Animals, Heian–Kamakura periods, 12th–13th century, section mounted as a hanging scroll, ink on paper, Collection of Robin B. Martin

This sculpture commemorates the arrival of a kami on a cloud-borne deer at Kasuga Taisha, a Shinto shrine near Nara dating to the eighth century. Rising from the deer’s back is a sakaki tree, an evergreen sacred to Shinto. Engraved on the disc or mirror in its boughs are images of the five Buddhist deities worshipped at Kasuga Taisha’s five shrines, evidence of the fusion of Shinto and Buddhist beliefs. The artist rendered the deer and sakaki tree in realistic detail, even including insect-chewed leaves.

Unknown Artist, Deer Bearing Symbols of the Kasuga Deities, Nanbokuchō era, 14th century, bronze, wood with pigments, Hosomi Museum, Kyoto

Falconry (hunting with birds of prey) was a sport favored by shoguns and high-ranking samurai. This unusual screen presents hawks “off duty” in the well-appointed mews where they were housed during their molting season, identified as summer by the flowering wisteria. With birds of various ages silhouetted against a golden ground and chicks in an artificial nest, this peaceful, almost domestic scene represents powerful goshawks less as predators than as evocations of the stability of the Tokugawa regime.

Kanō School, Goshawk Mews, Edo period, c. 1675, six‑panel screen, ink, color, and gold leaf on paper, Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Douglas J. Cooper, 1978

Standing on its toes and coyly bending its paws, the shape-shifting fox portrayed in this netsuke is in the middle of a wily transformation. In folklore, foxes are tricksters who turn into attractive women to seduce unwitting men.

Unknown Artist, Dancing Fox, Edo period, 18th century, ivory with staining, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Raymond and Frances Bushell Collection

Shaka is the Japanese name for the historical Buddha, who lived and died in India in the sixth century BC. On learning of his death, all living beings gathered at his side to mourn his passing into the blessed state known as Nirvana. Here, Shaka lies on his funeral bier, already transformed into a deity of superhuman size. His mother, Maya, flies in on a cloud at upper right, while deities, disciples, and both real and imaginary animals express various stages of grief. The central image of mourning is flanked by scenes illustrating important events in the Buddha’s life. Large hanging scrolls such as this are used for the annual Buddhist rite in memory of Shaka’s passing.

Unknown Artist, Shaka Passing into Nirvana, Edo period, 1727, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Seiraiji, Aichi Prefecture

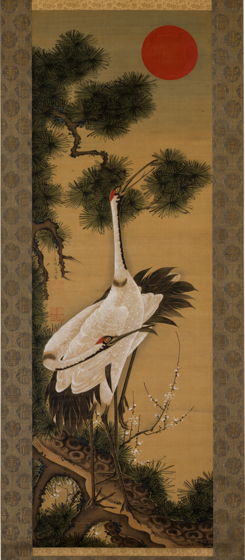

The complex poses of these two cranes, one encircling the other, are typical of Jakuchū’s unconventional approach to traditional subjects. His subtle layering of pigments captures textures ranging from stiff pine needles to soft plumage. Cranes—thought to live for a thousand years—and evergreens both symbolize longevity. Probably painted for use in New Year’s Day celebrations, the scroll depicts the cranes at dawn, greeting the first sunrise of the year.

Itō Jakuchū, Pair of Cranes and Morning Sun, Edo period, c. 1755–1756, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Tekisuiken Memorial Foundation of Culture, Chiba Prefecture

Made for the daughter of a wealthy merchant, this wedding garment features a large phoenix, mythical king of the birds, spreading its wings over peacocks, doves, pheasants, parrots, and chickens. In Japan, the number one hundred is normally used generally to signify abundance, but here it is literally true.

Unknown Artist, Uchikake with Phoenix and Birds, Meiji period, 19th century, silk crepe, paste‑resist dyed, Kyoto National Museum

The Buddhist sculptor Kōun turned to secular subjects during the Meiji period, when Buddhism was suppressed in favor of the native Shinto religion. He borrowed an actual monkey used as an attraction at a teashop to study while creating this dramatic, dynamic sculpture. It won a gold medal when exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and it has been designated an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government.

Takamura Kōun, Aged Monkey, Meiji period, 1893, wood, Tokyo National Museum

Kusama Yayoi, Shō‑chan, Heisei period, 2013, fiberglass‑reinforced plastic, paint, Private collection

Utagawa Yoshitora, Picture of the Twelve Animals to Protect the Safety of the Home, Edo period, 1858, woodblock print, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Sturgis Bigelow Collection

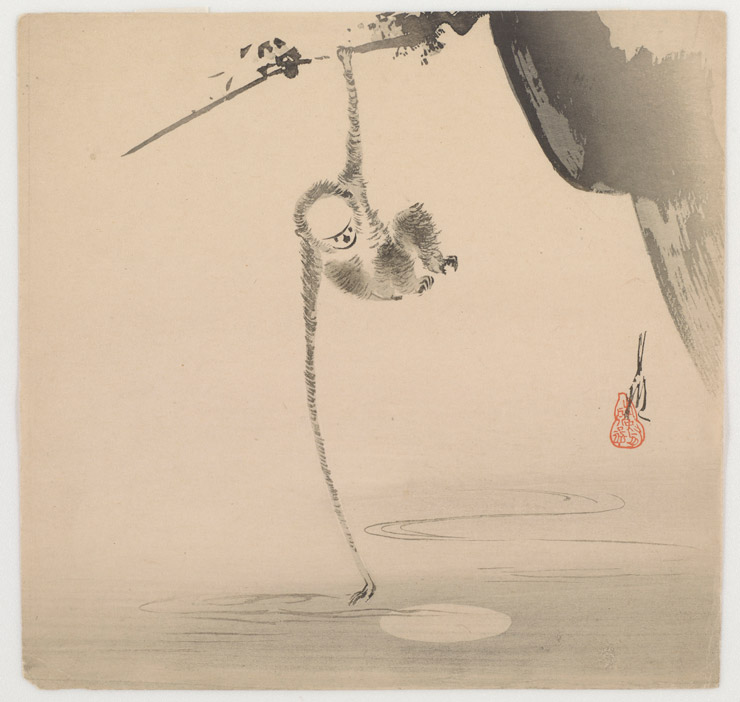

Ogata Gekkō, Monkey Reaching for the Moon, Meiji period, c. 1890 – 1910, woodblock print, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Robert O. Muller Collection, S2003.8.1669

Kōen, Monju Bosatsu Seated on a Lion with Standing Attendants, Kamakura period, 1273, set of five statues; wood with pigments, metal leaves, crystal eyes, Tokyo National Museum; Important Cultural Property

Miyagawa Kōzan I, Footed Bowl with Applied Crabs, Meiji period, 1881, stoneware with brown glaze, Tokyo National Museum; Important Cultural Property

Issey Miyake, Swallow Pleats, Heisei period, 1999, polyester, Miyake Design Studio

Unknown artist, Sacred Foxes, Kamakura period – Nanbokuchō era, 14th century, wood with pigments, Kiyama Jinja, Okayama Prefecture

Unknown artist, Kyōgen Monkey Mask, Edo period, 17th – 18th century, wood, gesso, pigments, Tokyo National Museum

Unknown artist, Charger with Carp Ascending Waterfall, Edo period, 19th century, Arita ware, porcelain with celadon glaze and underglaze blue, Segawa Takeo

Unknown artist, Yogi with Crane and Turtle, Edo period, 19th century, silk crepe, paste-resist dyed, Matsuzakaya Collection

Kaigyokusai Masatsugu, Wild Boar, Edo – Meiji periods, mid-to-late 19th century, netsuke; ivory with ink, inlays, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Raymond and Frances Bushell Collection

Nawa Kohei, PixCell-Bambi #14, Heisei period, 2015, mixed media, Collection of Ms. Stefany Wang

Unknown artist, Helmet Shaped like a Turbo Shell and Half Mask, Edo period, 17th century, iron, gold, silver, wood, paper, lacquer, silk, hemp, horse hair, Tokyo National Museum