George de Forest Brush: The Indian Paintings

Overview

For more than a year, starting in 1882, George de Forest Brush (1854/1855–1941) lived among the Arapahoe and Shoshone in Wyoming and the Crow in Montana. He began to compose and exhibit studio paintings based on his experiences, declaring, however, that he did not wish to be an ethnographer or historian of Indian people. Painting during a period bracketed by the Battle of the Little Big Horn (1876) and the massacre at Wounded Knee (1890), the artists created stylized images of Indians far removed from the reality of contemporary Indian life. Instead, Brush’s “Indian” paintings are unmistakably personal. Increasingly disturbed by the rapid industrialization and mechanization of American society, Brush offered, in his art, the perfect foil–a seductively beautiful, pre-industrial world where idealized Indians live in a timeless environment undisturbed by the advent of the modern.

Born in Tennessee, raised in Brooklyn and in Darien, Connecticut, Brush began his academic training at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1870. Three years later he journeyed to Paris to continue his training under the tutelage of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most admired academic painters of the day. Following six years of travel and study, Brush returned to New York determined to find an American subject that would set him apart from his contemporaries. In the spring of 1882, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains and among America’s native people, he found his subject.

Brush initially expressed a desire to explore in his paintings experiences common to all, such as the grief of the woman in Mourning Her Brave, his first major success. The artist’s agenda was, in fact, more complicated. For Brush, the figure of the Indian became a metaphor through which he could address his concern that a nation racing toward modernism was losing its regard for art born of craft and tradition. The artist’s technically exquisite and contextually rich Indian paintings have been brought together for the first time in this exhibition.

Self-Portrait, before 1890, oil on canvas, National Academy Museum, New York

Mourning Her Brave, 1883, oil on panel, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

The Revenge, 1882, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Alex Simpson, Jr., Collection, 1944

An Arapahoe Boy, c. 1882, oil on canvas (grisaille), Gift of Jane Wyeth, in memory of her parents, Gertrude Ketover Gleklen and Leo Gleklen, 2007.138.1

A Young Shoshone, 1882, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Old Washakie, 1884, oil on panel, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie

The Picture Writer's Story, 1884, oil on canvas, The Anschutz Collection

The White Swan, 1885, oil on panel, Russell and Michelle Ball Collection

Studio Paintings

In the fall of 1883, after his experiences in Wyoming and Montana, Brush returned to New York, where he began teaching the “Antique Class” at the Art Students League. For generations, aspiring art students had honed their drawing skills by copying plaster casts of classical sculpture. Once the reached a certain level of proficiency, they were permitted to sketch from life models.

While teaching young art students how to draw the human figure from casts and models, Brush created a series of Indian paintings that reflected both his own academic training and his reverence for artistic tradition. In their physical perfection, the Indian figures in Brush’s paintings display an ideal of beauty defined centuries earlier in ancient Greece and later perpetuated in art academies in both Europe and America.

Many of the figures in Brush’s paintings are shown in poses common in studio classrooms – for example in Before the Battle, a warrior’s lance replaces the balance pole that allowed models to hold poses for extended periods. The artist’s Indian figures also echo masterpieces of Renaissance sculpture, including Michelangelo’s monumental David – the inspiration for the central figure in Before the Battle.

The dazzling surface layer of Brush’s paintings, accomplished through a painstaking technique learned in Paris, presents and illusory sense of reality. Beneath the apparent fidelity to nature lies a picture fabricated in the artist’s imagination.

Before the Battle, 1886, oil on canvas, Private Collection, Wyoming

The Silence Broken, 1886, oil on canvas, Collection of David H. Koch

Indian Hunting Cranes, 1887, oil on canvas, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold F. Wendel

The Indian and the Lily, 1887, oil on canvas, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Portrait of an Indian, c. 1887, oil on panel, Private Collection

Indian Hunter, 1890, oil on panel, Private Collection

Indian as Metaphor

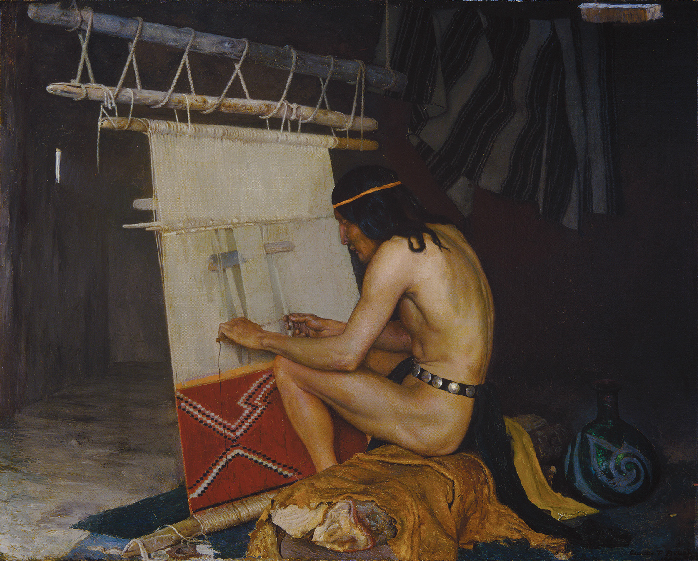

As the decade of the 1880s drew to a close, Brush increasingly focused on compositions in which a single Indian figure is shown engaged in the creation of art. Whether weaving a rug or carving a stone wall, isolated individuals appear completely absorbed in the creative process. Among the finest of these works are his so-called Aztec paintings, which may have been inspired by the “Aztec Fair,” a popular commercial road show that opened in New York in the fall of 1886. In addition to a “large collection of Aztec antiquities,” the fair boasted more than fifty Mexican artisans demonstrating such skills as weaving and onyx carving.

Shortly after the fair closed, Brush exhibited An Aztec Sculptor, the first of his Aztec series, which also includes The Sculptor and the King and The Crane Ornament. In these works, confined interior spaces replace the landscape settings of Brush’s earlier paintings. Artists, rather than warriors or hunters, become the focus. Capitalizing on renewed interest in Central American generated by the Aztec Fair, Brush created images celebrating an American tradition of craftsmanship ancient in origin that he, like his contemporaries, viewed as a parallel to the Greco-Roman tradition claimed by Europeans.

Implicitly autobiographical, these paintings reflect Brush’s growing concern that artisanship–the craft of making art–was losing its value as mechanization led to the replacement of the handmade object with the mass-produced. In a surprising way, these spare, late Indian paintings emerge as works of protest–Brush’s visual response to a society eager to embrace the modernism he resisted.

An Aztec Sculptor, 1887, oil on wood, Gift (Partial and Promised) of the Ann and Tom Barwick Family Collection, 2005.107.1

The Sculptor and the King, 1888, oil on panel, Portland Art Museum, Oregon, Bequest of Miss Mary Forbush Failing

The Weaver, 1889, oil on canvas, Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Daniel J. Terra Collection

The Crane Ornament, 1889, oil on panel, Private Collection

The Head Dress, 1890, oil on canvas, Property of the Westervelt Company and displayed in the Westervelt-Warner Museum of American Art, Tuscaloosa Alabama