American Masters from Bingham to Eakins: The John Wilmerding Collection

Introduction

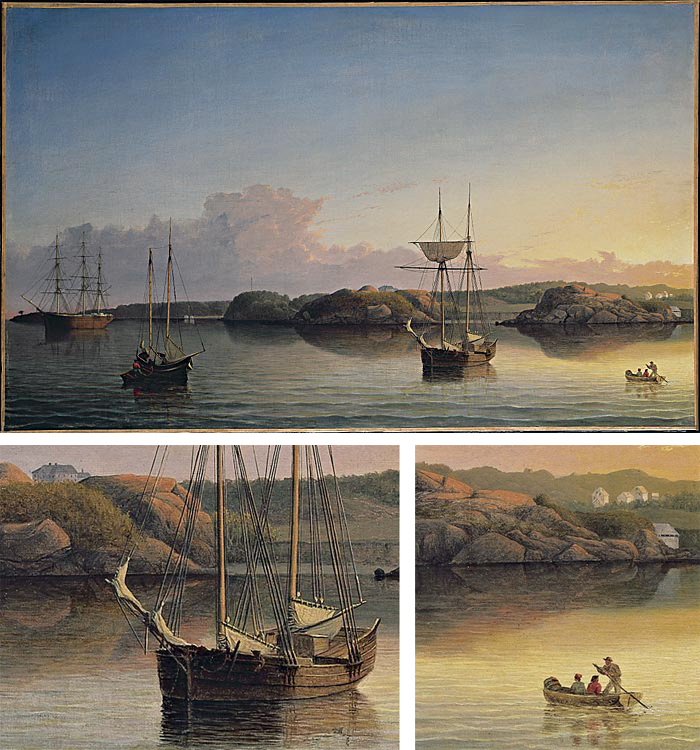

Over the course of his career as a professor and museum professional, John Wilmerding has become one of the most widely known and respected authorities on American art. Since the 1960s, his many books and articles have helped define the scholarly nature of the field and also have documented the work of such key figures as Fitz Henry Lane, Winslow Homer, and Thomas Eakins. Although Wilmerding's scholarship is well known, his art collection is less familiar. Since the acquisition of his first painting (Lane's harbor scene, above) in 1960, Wilmerding has sought out works that parallel his own scholarly interests in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American art: tranquil landscapes and seascapes by Martin Johnson Heade and Fitz Henry Lane, still lifes by John F. Peto and Joseph Decker, figure paintings by Homer and Eakins, and paintings and drawings by artists who visited Maine's Mount Desert Island. His collection also includes important works by Frederic Edwin Church, George Caleb Bingham, and John F. Kensett.

At the opening of this exhibition, Wilmerding announced that all of the paintings and drawings in the much-anticipated show would remain at the National Gallery of Art--a gift to the nation. Since his association with the Gallery began, Wilmerding carefully considered how his personal acquisitions might one day both fill gaps and build on strengths in the Gallery's existing collection. Through his generosity, the Gallery will now have its first work by George Caleb Bingham, its first oil painting from Winslow Homer's Cullercoats period, its first marsh scene by Martin Johnson Heade, its first watercolor by Thomas Eakins, its first European landscape by John Frederick Kensett, its first oil study by Frederic Edwin Church, its first drawings by Ralph Albert Blakelock and Fitz Henry Lane, and its first works in any medium by Alfred Thompson Bricher, Adelheid Dietrich, Thomas Charles Ferrer, Alvan Fisher, Jervis McEntee, and Edward Seager.

For some forty years, John Wilmerding has introduced thousands of students and museum visitors to the wonders and complexities of our national art. With this remarkable gift to the National Gallery of Art, his superb collection of American masters will now educate and inspire millions.

Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Stage Rocks and Western Shore of Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1857, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

George Caleb Bingham's most admired paintings depict the often rowdy lives of men who transported cargo on the Mississippi and other frontier rivers. After rowing shallow draft flatboats to trading posts and packing them with furs, foodstuffs, and other goods, they would float downriver to junctions where the freight would be loaded onto steamboats or railroads for transport to eastern markets. While waiting in riverside towns for the arrival of the larger vessels, the boatmen often passed their time gambling, drinking, and carousing.

In Mississippi Boatman, a grizzled veteran of the river sits guarding cargo and eyeing us warily; behind him a moored flatboat awaits the next journey upriver. He seems older than the usual characters that populate Bingham's genre scenes, and his shabby shirt, worn trousers, and scuffed boots suggest his down-and-out circumstances. The man's world-weary expression also conveys a sense of resignation. River life was changing drastically at mid-century. Steamboats carried more of the cargo, and cities and towns were replacing the more rambunctious trading posts. Although eastern audiences still viewed Bingham's characters as archetypes of the frontier--rugged individuals willing to make their living on the fringes of civilized society--in reality, by mid-century the golden era of the flatboatmen was drawing to a close.

George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879), Mississippi Boatman, 1850, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

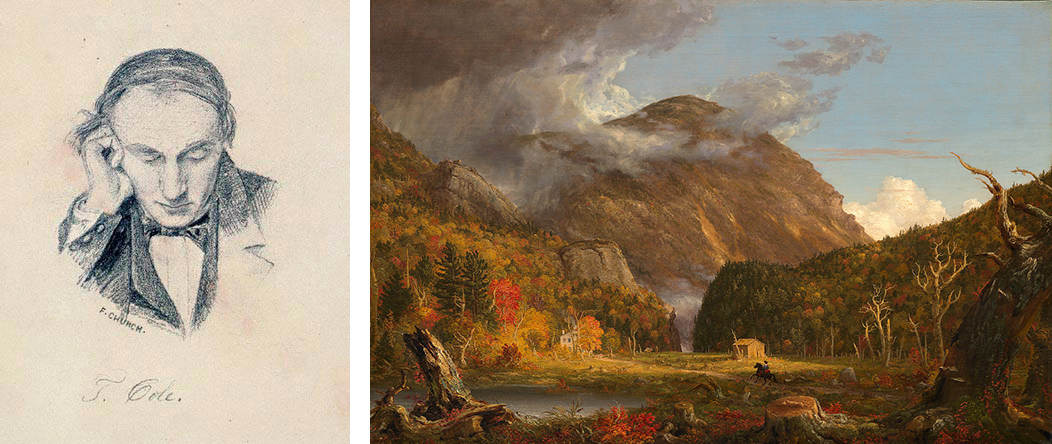

Frederic Edwin Church began his career apprenticed to the famed Hudson River landscape painter Thomas Cole (1801-1848). In addition to practical art instruction, the deeper lessons Cole conveyed about the purposes of landscape painting and the role of the artist in society would have greater and lasting importance.

Church never forgot his debt to his teacher. Late in life he wrote, "Thomas Cole was an artist for whom I had and have the profoundest admiration." This small, surely drawn portrait of Cole is evidence of Church's fondness for his teacher. Cole believed the intellect was paramount in creating great works of art. He wrote, "If the imagination is shackled, and nothing is described but what we see, seldom will anything truly great be produced in either Painting or Poetry."

(left) Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Portrait of Thomas Cole, c. 1845, pencil on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

(right) Thomas Cole (1801–1848), A View of the Mountain Pass Called the Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch), 1839, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1967.8.1

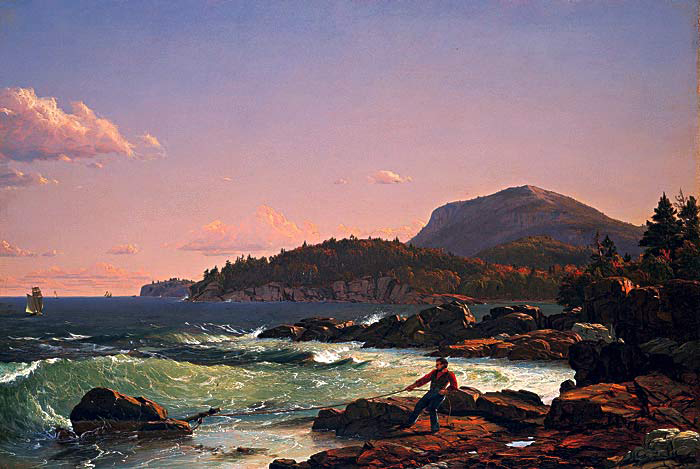

In the summer of 1850 Church traveled to Mount Desert, the first of many visits he would make to Maine over the course of his life. As he described in a letter: "It was a stirring sight to see the immense rollers come toppling in, changing their forms and gathering in bulk, then dashing into sparkling foam....We tried painting them, and drawing and taking notes of them, but cannot suppress a doubt that we shall neither be able to give the actual motion nor roar to any we may place upon canvas." Despite his words, Church must have felt he succeeded, for in 1851 he sent this work to a public exhibition in New York.

Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), Fog off Mount Desert, 1850, oil on academy board, John Wilmerding Collection

This painting is based on several pencil sketches Church had made in August and September 1850. The view moves from a rocky foreground with breaking waves, similar to those seen in Fog off Mount Desert, to the distinctive rocky profile of Newport Mountain (now know as Champlain Mountain), rising over 1,000 feet above the sea and the highest point on the eastern shore of the island. The prominence given to the figure in the foreground, who hauls the remnants of a sailboat's mast in by means of a rope, is unusual in Church's work. Perhaps this bit of wreckage was meant to remind viewers of the dangers of the sea--dangers that the several vessels in the distance might also face one day.

Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), Newport Mountain, Mount Desert, 1851, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

During his thirty-year career, Decker created landscapes, genre scenes, and a few portraits, but his most numerous subjects (more than half his total works) and those for which he is now best known are still lifes. Still Life with Crab Apples and Grapes comes from the first half of Decker’s career, when his style was crisp and hard-edged and his colors were forceful. Each spherical shape of apple or grape shines, spotlighted against a dark background. While the grapes he depicts are robust, virtually perfect specimens of cultivated fruit, the crab apples are varicolored, poked, and pockmarked, and one is even roughly cut open. Together these objects are arrayed across an indeterminate reflective surface, creating a composition of syncopated rhythm.

(top) Joseph Decker (1853–1924), Still Life with Crab Apples and Grapes, 1888, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

Born in Wittenberg, Germany, Adelheid Dietrich was the daughter and pupil of the painter Eduard Dietrich (1803–1877). Some fifty works by Dietrich are known. Nearly all are flower paintings characterized by a crystalline intensity and painted in the finest detail and with extraordinary technical facility. These botanical subjects are much in the manner of seventeenth-century Dutch still-life painters, particularly as filtered through the eyes of nineteenth-century northern European artists.

Still Life with Flowers includes about a dozen varieties of grasses and blooms of varied colors and textures. In its baroque profusion this work is typical of the sense of abundance that characterizes much still life in the second half of the nineteenth century, but Dietrich’s images also have an exquisite grace and delicacy. She often painted complex works, some with flower-strewn rocks seen against blue skies, but her most effective still lifes seem to be her smaller, more compact compositions, placed in quiet interiors. The present example, and others of around this date, often utilize a wonderfully illusionistic glass vase at the center of the arrangement and a single source of light illuminating the blossoms against a dark background.

Adelheid Dietrich (1827-1891), Still Life of Flowers, 1868, oil on wood, John Wilmerding Collection

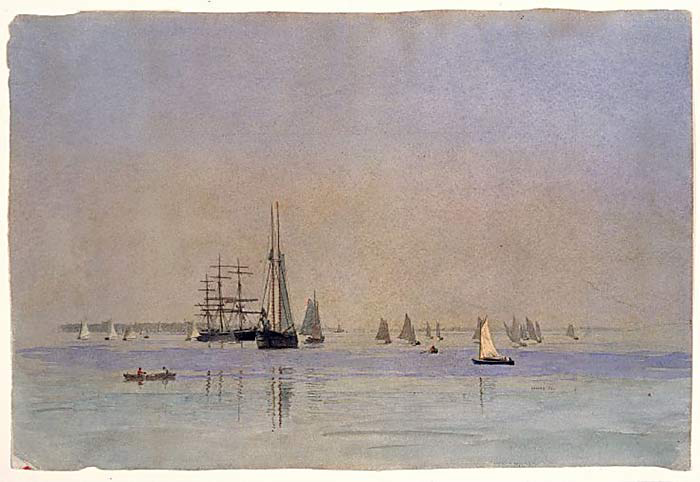

Watercolors such as Drifting were not conceived as independent works or studies for paintings, but rather as works done after paintings. The artist may have been creating watercolor copies of his oils to take advantage of the new vogue for the medium. While they mirror the meticulous detail of the paintings, their luminescent quality is very different from the oils they often follow. The watercolors are suffused with light supplied by the white ground of the paper and feature subtle atmospheric effects--qualities that frequently eluded Thomas Eakins in his great subject paintings, whose dark tonalities troubled the artist and were often the target of contemporary criticism.

Drifting simply and directly captures the play of light across the water and on the sails of the boats. Eakins reduced the scene to a few basic elements: the shoreline; a tall, dark sail silhouetted against the sky with the hull of another boat positioned at an oblique angle behind it; and a small boat with a white sail in the right foreground. Although Drifting would not have required the complex calculations needed to depict the foreshortening of the racing shells seen in his well-known rowing images, the artist may have used perspective sketches to calibrate the wave patterns and the recession in space toward the horizon line. The extraordinary detail in this work may also owe something to Eakins’ experiments with photography.

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), Drifting, 1875, watercolor on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

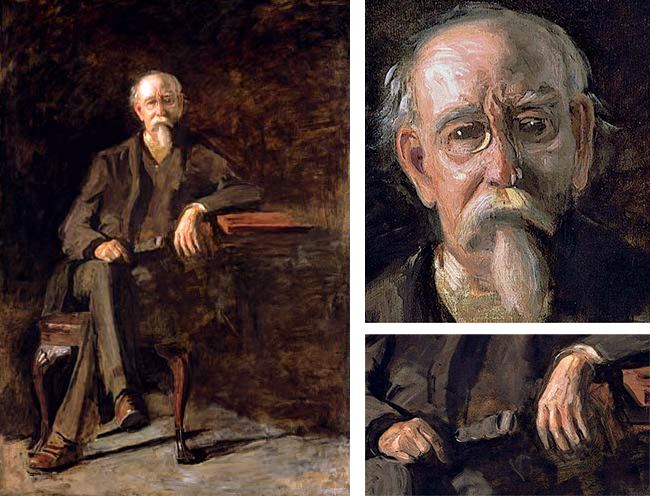

Dr. William Thomson (1833-1907), a pioneer in the treatment of eye diseases, was the subject of Thomas Eakins’ last full-length portrait. With this oil study for the finished painting (now at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia), Eakins captured his sitter’s likeness in one of the most empathetic portraits of his career. By the time Eakins asked Thomson to sit for him in 1906, the two men were well acquainted: Eakins had been one of Thomson’s patients for more than a decade, and the two had long shared a fascination with optics and the complexities of vision. Dr. Thomson was one of Eakins’ few contemporaries who knew that the artist was losing his sight. In this full-scale study, Thomson looks directly at the artist. He holds, appropriately, an ophthalmoscope, an instrument used to examine the interior of the eye. This portrait remained in Eakins’ studio until his death in 1916.

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), Portrait of Dr. William Thomson, 1906, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

In 1877 Thomas Eakins painted a canvas showing the early Philadelphia ship carver and sculptor William Rush (1756–1853), working from a nude female model in sculpting a life-size allegorical figure. The only other figure present in the painting is an elderly woman knitting. Although there is no evidence the sculptor had worked from a nude model, Eakins believed study from the nude was essential and he stressed this in his teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The 1877 painting may have been intended to suggest that working from the nude was not unprecedented in Philadelphia. The inclusion of the elderly woman chaperone legitimized the activity of posing nude, making it clear that this model was a virtuous young woman from a good family.

Even so, for many Philadelphians of Eakins’ time the idea of such a person posing nude would still have carried an unmistakable implication of scandal. In 1886 Eakins was forced to resign his position at the Pennsylvania Academy, in part because his unrelenting emphasis on working from the nude had become a controversial topic in staid Philadelphia. Rumors circulated that Eakins had indulged in improper, even immoral behavior. The dismissal affected him deeply and he increasingly withdrew from Philadelphia art circles to pursue his art independently. By the early 1900s he was all but forgotten.

In 1908 Eakins returned to the subject of William Rush in several paintings. The most complete version, for which The Chaperone is a study, retains the principal elements from the 1877 oil, but with significant changes. The figure of Rush is presented as an artisan or a workman and the chaperone is no longer a finely dressed, elderly white woman in an elegant chair, but rather a black woman wearing a bandanna. Eakins presumably made this oil sketch from life, but we do not know the sitter's identity. Eakins gave her a quiet dignity that differs markedly from the less sympathetic images of African Americans found in all too many works by his contemporaries.

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), The Chaperone, c. 1908, oil on canvas, Gift of John Wilmerding, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1991.34.1

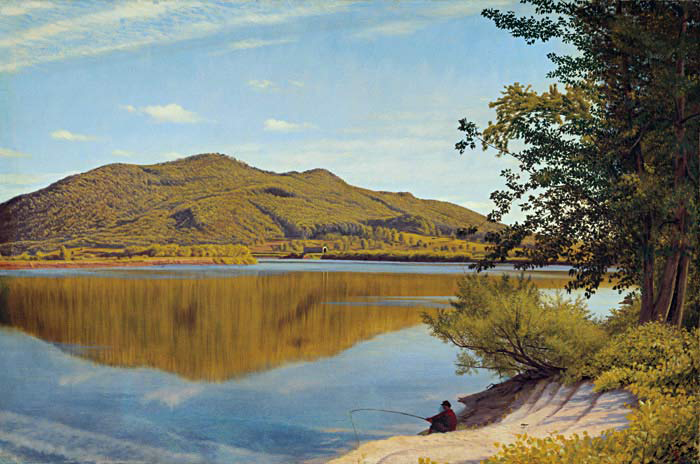

British-born Thomas Charles Farrer produced painstaking, minutely observed images, reflecting the writings of John Ruskin, the influential critic who valued "truth to nature" above all other aesthetic qualities. Mount Tom was painted in the summer of 1865 when Farrer and his wife visited the Connecticut River Valley near Northampton, Massachusetts, a popular destination for nineteenth-century travelers in search of picturesque landscape.

Thomas Charles Farrer (1839-1891), Mount Tom, 1865, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

This is the earliest known still life and flower subject by Martin Johnson Heade. The four floral still lifes in the Wilmerding collection (nos. 11-14) all date from the 1860s--a period during which Heade perfected his style and emerged as one of the first important flower painters in American art.

Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Still Life with Wine Glass, 1860, oil on board, John Wilmerding Collection

A soft light from the left defines the pristine ovoid of the tinted Parianware vase and casts a shadow behind it. The curtain on the left is pulled back to reveal the vibrant violet blossoms of the heliotrope and the rich creamy pinks and yellows of the rose petals. This gesture adds a note of both drama and decorum and provides a subtle visual threshhold for the painting. The logically ordered foreground deftly draws attention toward the flower arrangement.

Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Roses and Heliotrope in a Vase on a Marble Tabletop, 1862, oil on board, John Wilmerding Collection

Heade presents his bouquets theatrically. The Victorian vases wtih their sensuous shapes and distinctive styles evoke female forms, and the floral arrangements burst forth expressively, almost like soloists on a bare stage. This anthropomorphic quality becomes even more pronounced in Heade's paintings of orchids and magnolias of the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s. The art historian John I.H. Baur once observed that works like Heade's Giant Magnolias on a Blue Velvet Cloth, with their "fleshy whiteness," resemble "odalisques on a couch."

Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Apple Blossoms in a Vase, 1867, oil on board, John Wilmerding Collection

The dramatic composition of the white lilies against the dark background creates an ominous, almost surreal mood, not unlike that found in Heade’s pictures of thunderstorms from the same period. In addition, the palpable vitality of the flowers suggests they are moving, foreshadowing the animated qualities of the artist's tropical orchid subjects of the early 1870s.

Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Still Life with Roses, Lilies, and Forget-Me-Nots in a Glass Vase, 1869, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

Newbury is at the mouth of the Parker River in Massachusetts and just south of Newburyport, the site of Heade's first paintings of marshlands made around 1859. Heade executed well over one hundred marsh subjects during his career, exploring numerous arrangements of his theme's basic elements of pasture, haystacks, and sky. His paintings offer nuanced descriptions of the tides, meteorological phenomena, and other natural forces that shaped the appearance of the swamp, but he also shows how men hunted, fished, and hayed the marshes and used them as pasture for their cattle. With its lurid pink thunderheads looming ominously over a peaceful landscape, Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes unites the aesthetic categories of the sublime and the beautiful.

Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes, c. 1871-1875, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection, 2010.74.1

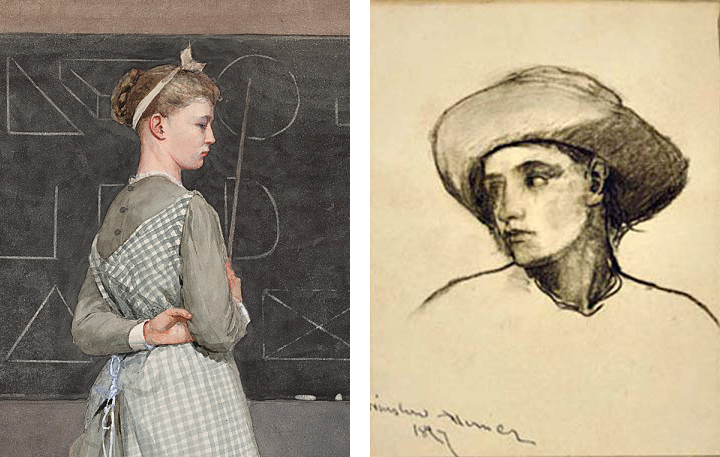

As is so often the case with Winslow Homer's images, the subject seems to be contemplating something beyond the pictorial space, yet we are given no clue what may have drawn it. The artist's reluctance to set up narratives with clear resolution, coupled with his bold handling of line, give Head of a Boy its considerable strength.

(left) Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Blackboard (detail), 1877, watercolor on wove paper, Gift of Jo Ann and Julian Ganz, Jr., in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.60.1

(right) Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Head of a Boy, 1877, pencil on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

In March of 1881 the artist sailed from New York to London. He settled in the village of Cullercoats on the North Sea, just below the Scottish border. The tightly knit community consisted mainly of fishermen and their families. In this painting, several women are knitting or darning near the entrance to a seventeenth-century cottage called Sparrow Hall; on the steps, a girl protectively steadies a younger child who dangles a bit of blue yarn in front of a calico cat.

Such hearty, industrious women were a constant source of inspiration to Homer. During the year and a half he remained in Cullercoats, the artist produced some of his most lyrically beautiful work. Sparrow Hall, wonderfully conceived, brightly colored, and superbly painted, stands very high among those works, and indeed among Homer's images from any period. This is one of the few finished oils produced in Cullercoats; most of his work abroad was done in watercolor. Homer's stay in Cullercoats marked a critical turning point in the artist's career; upon his return to the United States, his painting took on a newfound sense of gravity and monumentality that would characterize his mature style.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Sparrow Hall, c. 1881-1882, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

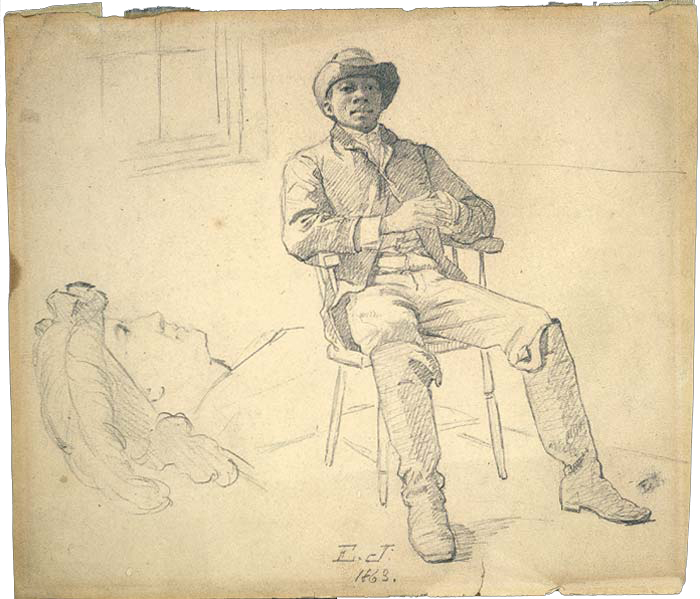

Skillfully drawn and expertly shaded, the figure shares the page with a brief outline of a window casement and a sketch of a woman wearing a feathered hat and a snood (hairnet). Seated in what may be a captain's chair, the young man engages the viewer directly. His boots, jacket, and high-buttoned shirt suggest a livery costume. It is possible that the youth (likely a freedman) was employed to assist with military horses, coaches, or wagons. Although drawn with great care, as if intended to serve as a preparatory sketch for a studio painting, no larger work incoporating this figure has been identified. Eastman Johnson was one of America's most acomplished genre painters. His willingness to produce images that touched on the most hotly debated issue of the day--the abolition of slavery--thrust Johnson to the forefront of those willing to address African American subjects on the eve of the Civil War.

Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), Seated Man, 1863, pencil on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

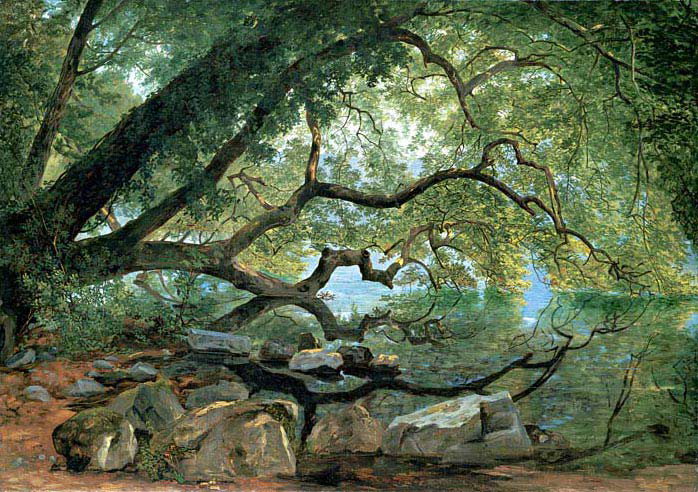

Although Kensett is best known for his American landscapes, he also created a number of important works while residing in Europe from 1840 to 1847. This painting is one of a series of plein-air or outdoor oil sketches Kensett made during a tour of sites south and west of Rome during the summer of 1846. Such works were never intended for exhibition, but later in the century were made more widely available at memorial exhibitions like the one held for Kensett in 1873 at the National Academy of Design in New York, where An Ilex Tree on Lake Albano, Italy, was shown publicly for the first time.

John Frederick Kensett (1816-1872), An Ilex Tree on Lake Albano, Italy, 1846, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

Fitz Henry Lane, known as a marine painter, based this painting on drawings he made from the center of his hometown Gloucester's harbor. The western shore was believed to be the place where the French explorer Samuel de Champlain landed early in the seventeenth century. In a letter Lane noted that he had been given "an order for a picture from this point of view, to be treated as a sunset. I shall try to make something out of it, but it will require some management, as there is no foreground but water and vessels." Lane "managed" the painting beautifully, animating the foreground expanse of water with various large and small vessels arranged in a zigzag pattern that is mirrored by the contours of the shore.

Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Stage Rocks and Western Shore of Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1857, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

Lane's last dated works were several small oils of Brace's Rock, which is situated at the end of a ledge that forms one side of Brace's Cove. The name is believed to have come from the Middle English word for arm; now obsolete, it meant in nautical terms an arm of the sea, or cove. The cove was frequently mistaken for the entrance to Gloucester's harbor, which actually lies a mile further on, and shipwrecks there were common. Painted when the artist was in failing health and the nation was embroiled in the Civil War, this quiet and still image of an abandoned boat on a lonely stretch of rocky coast attains a poignancy that is unsurpassed in Lane's work.

Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Brace's Rock, Eastern Point, Gloucester, c. 1864, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

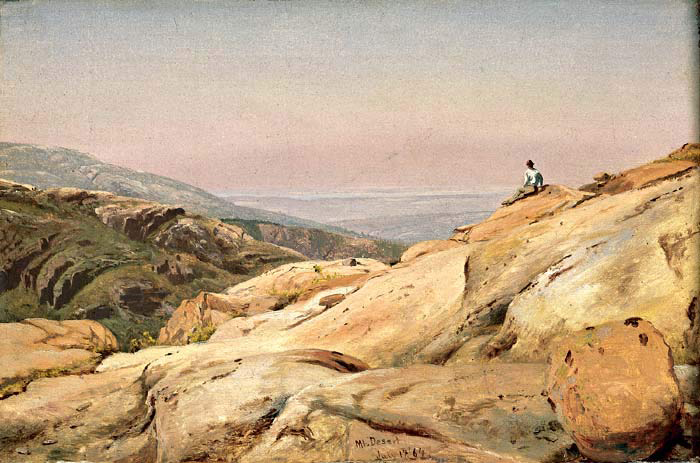

Jervis McEntee first studied landscape painting with Frederic Church. He worked alongside Church, Sanford R. Gifford, and Worthington Whittredge in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York, and was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1861. McEntee and Gifford were close friends, and they often went on sketching expeditions together to "enjoy the wild beauty of the lovely lakes and mountains...." This optimistic and celebratory painting, filled with naturalistic effects of light and atmosphere, shows an artist and adventurer actively taming nature. It can be debated whether the essentially anonymous figure with its back turned to the viewer in this work is Gifford or McEntee, but regardless of the identification, the painting was clearly inspired by the experience of one artist seeing the other alone at work in the landscape. Inevitably, Mount Cadillac became accessible to tourists; by the 1880s, in the wake of the building of a railway to the summit, the once remote location was drawing thousands of summer visitors.

Jervis McEntee (1828-1891), Mount Desert Island, Maine, 1864, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

Today, John Frederick Peto is recognized as one of America's most important still-life painters. The mystery and solemnity of his library compositions result not only from the rich palettes and the somber, suggestive lighting of these works, but also from the implied histories of the worn and torn objects that are presented. While the battered volumes reflect human struggle, they also suggest the triumph of creativity. As John Wilmerding has written, "Peto's books stand as embodiments of culture as diverse as the shapes and colors of the volumes themselves. For him books were more than inert things lying around tables or shelves; they were unexpected but accessible incarnations of art."

John Frederick Peto (1854-1907), Take Your Choice, 1885, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

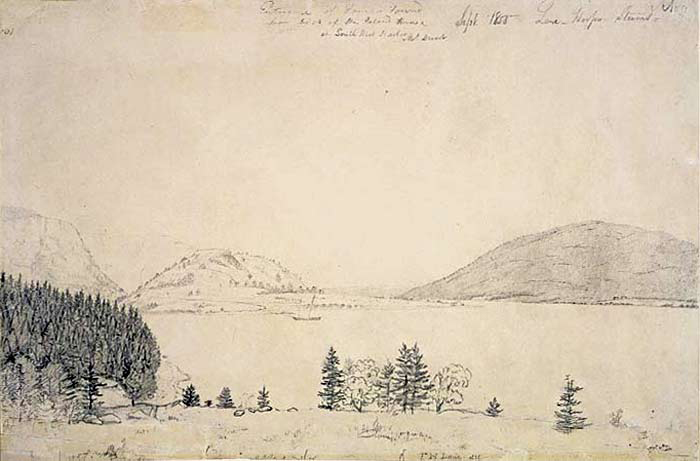

The drama of Maine's rocky coast has long attracted American artists. One of the grandest sites in an indisputably scenic area is Mount Desert, an island approximately 108 miles square, located about two-thirds the way up the Maine coast. Named "Isle de Mont-Deserts" by the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, for its thirteen barren peaks, the island was settled by descendants of English fishermen, farmers, boat builders, and lumbermen.

Map by Wendy Schleicher Smith

Beginning in the 1830s and 1840s with Thomas Doughty, Alvan Fisher, and, most importantly, the renowned Thomas Cole, who went there to sketch in 1844, artists succumbed to Mount Desert's splendid views. Despite its remoteness, or perhaps because of it, well-known figures such as Frederic Church and Fitz Hugh Lane visited several times in the 1850s to record the island's wild and rugged beauty. The 1851 exhibition of Church's images at the National Academy of Design in New York City popularized the site for both professional and amateur artists.

With a boom in tourism at the end of the Civil War, Mount Desert became a common vacation destination, and its novelty faded somewhat among artists. Their depictions were less concerned with geologic correctness and detailed naturalism, emphasizing instead the island's evanescent qualities of light and atmosphere. Mount Desert eventually attracted affluent recreation-seekers, several of whom purchased and then presented to the government some of the island's most beautiful land, which later became the core of Acadia National Park.

Fitz Hugh Lane, Entrance of Somes Sound, Mount Desert, Maine, 1855, pencil on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

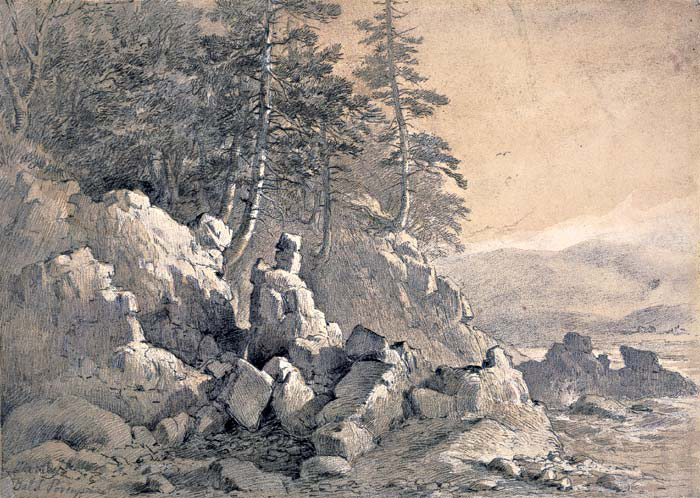

While his name may not be familiar today, Felix Octavius Carr Darley was a premier nineteenth-century American illustrator. He is thought to have produced some four thousand drawings, the majority of which were used as the basis for engraved magazine and book illustrations and banknote designs. Rocks near the Landing at Bald Porcupine Island, Bar Harbor, with its high degree of finish, is not a simple preparatory sketch but a drawing that was intended for exhibition and sale.

Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1822-1888), Rocks near the Landing at Bald Porcupine Island, Bar Harbor, 1872, pencil and wash on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

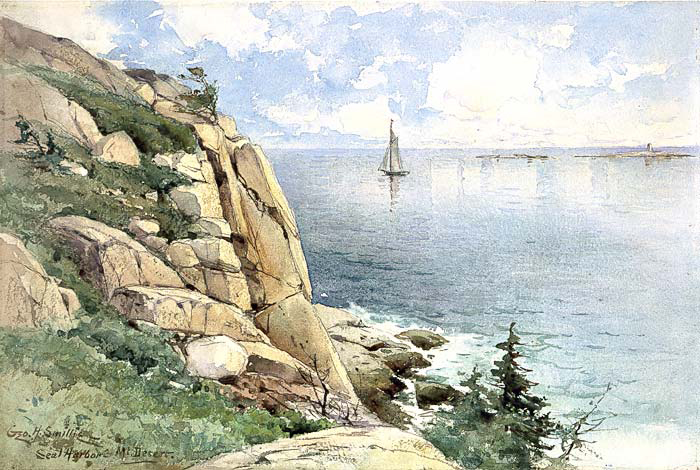

Although this watercolor conveys impressionistic effects of color and light, the work is based on careful draftsmanship. George Henry Smillie was less interested in objectively rendering optical effects than in conveying feelings and moods through his strikingly simplified compositions. He marveled at the fact that while landscape painting could be defined as a horizon crossed by a diagonal, it was a formula capable of expressing an endless variety of emotions. Late in his career he wrote, "The longer man lives the simpler grows the composition."

George Henry Smillie (1840–1921), Seal Harbor, Mount Desert, c. 1893, watercolor on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

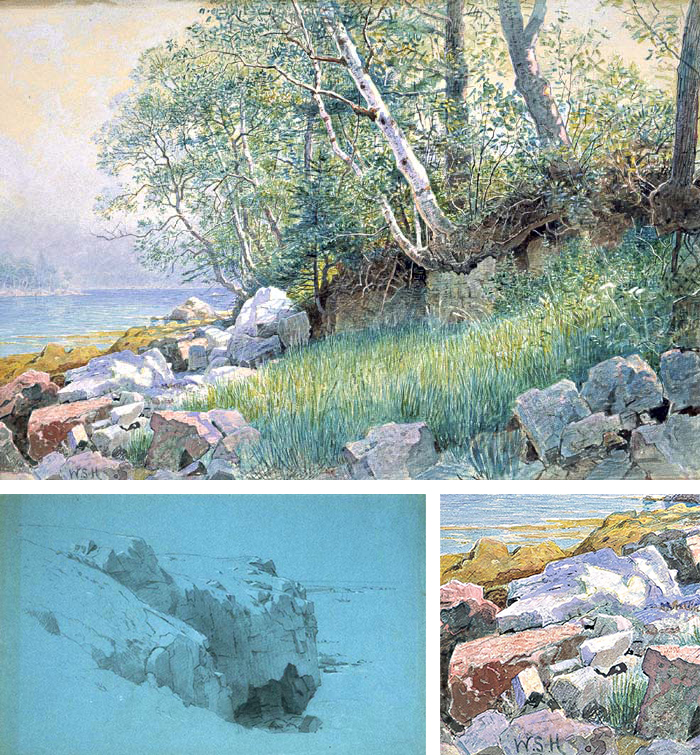

This exquisite, highly finished watercolor dates from 1895, when William Stanley Haseltine spent the summer with friends in Northeast Harbor on Mount Desert. Although the island had become one of the most fashionable resorts on the East Coast, dotted with palatial "cottages" built by the Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Morgans, and Astors, the landscape depicted here remains pristine. The Ruskinian attention to geological detail that characterized Haseltine's early work has given way to a more fluid presentation, delicate in color and imbued with a softly filtered light. Haseltine's daughter later wrote of the change in her father's work, acknowledging his debt to French impressionism by calling him a "Pre-Monet Impressionist."

(top) William Stanley Haseltine (1835–1900), Northeast Harbor, Maine, 1895, watercolor and Chinese white on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

(bottom left) William Stanley Haseltine (1835–1900), Otter Cliffs, Mount Desert (Looking toward Sandy Beach and Great Head), c. 1859, pencil and white chalkon blue paper, John Wilmerding Collection

(bottom right) William Stanley Haseltine (1835–1900), Northeast Harbor, Maine (detail), 1895, watercolor and Chinese white on paper, John Wilmerding Collection

History

While at the National Gallery of Art, John Wilmerding served as curator of American art and senior curator from 1977 to 1983 and as deputy director from 1983 to 1988. A number of remarkable paintings entered the National Gallery's collection during his tenure, including the Peale, Lane, and Heade canvases seen below. Wilmerding has also served as a member of the advisory board of the Gallery's Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts and, more recently, as a member of the Trustees' Council. He donated Eakins' oil sketch The Chaperone, which is included in this exhibition, in honor of the Gallery's fiftieth anniversary in 1991.

(left) Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860), Rubens Peale with a Geranium, 1801, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Patrons' Permanent Fund,

1985.59.1

(top right) Fitz Hugh Lane (1804-1865), Lumber Schooners at Evening on Penobscot Bay, 1863, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Francis W. Hatch, Sr., 1980.29.1

(bottom right) Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Cattleya Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds, 1871, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Gift of The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, 1982.73.1

Wilmerding's exhibitions--ranging from monographic shows on artists such as Fitz Hugh Lane and John F. Peto, to installations of important private collections and thematic exhibitions like the majestic American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850–1875--helped establish the American art department at the National Gallery and introduced literally thousands to our nation's artistic treasures.

John Wilmerding, 1980, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives

As an important collector of American art Wilmerding has assembled over the years a superb group of paintings and drawings from the mid-to-late 19th century. Other than friends and family members, relatively few have had the pleasure of seeing these works, because he has been characteristically modest about his activities as a collector. That he has now generously agreed to share his collection with a wider audience is indeed a cause for celebration.

John Wilmerding comes from a family with a rich history of collecting art. Wilmerding's great-grandparents, Henry Osborne Havemeyer and his second wife, Louisine Waldron Havemeyer, amassed an extraordinary group of European and oriental works of art that was eventually bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Renowned in its own day, as it still is today, for its old master and impressionist paintings and for its Chinese and Japanese precious objects, prints, and textiles, the Havemeyer Collection is among the most magnificent gifts the Metropolitan has ever received. One of the Havemeyers' daughters, Electra Havemeyer Webb (Wilmerding's grandmother), was an eclectic acquirer of American fine and folk paintings and sculptures, decorative arts, quilts, tools, vernacular objects, toys, buildings, and transportation vehicles. Her remarkable and vast collection was the genesis of the Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

Installation view of American Sampler: Folk Art from the Shelburne Museum, National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives

John Wilmerding is currently the Christopher Binyon Sarofim Professor of American Art at Princeton University and visiting curator in the department of American art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He is trustee emeritus of the Shelburne Museum in Vermont and a member of the boards of trustees of the Guggenheim Museum in New York and the College of the Atlantic in Maine. He serves on advisory boards or committees for Smithsonian Studies in American Art, the Archives of American Art, Harvard University Art Museums, and the Terra Foundation for American Art. He also holds a presidential appointment to the Committee for the Preservation of the White House.

Wilmerding is the author of many books and catalogues on American art, including American Marine Painting (1987); American Views (1991); monographic studies of Robert Salmon, Fitz H. Lane, John F. Peto, Winslow Homer, and Thomas Eakins; The Artist's Mount Desert: American Painters on the Maine Coast (1994); and Compass and Clock (1999). His most recent book, Signs of the Artist: Signatures and Self-Expression in American Painting (2003), is a study of autobiographical embodiments of artists in their works expressed through their signatures.

John Wilmerding, photograph by D. Applewhite

Credits

This Web feature was designed and produced by Donna Mann and edited by Ulrike Mills. Texts are based on the exhibition catalogue written by Franklin Kelly, Nancy K. Anderson, Charles M. Brock, Deborah Chotner, and Abbie N. Sprague. Thanks to Frank Kelly, Nancy Anderson, Wendy Schleicher Smith, Kristen Quinlan, Dwayne Franklin, Barbara Moore and, especially, John Wilmerding.

William Trost Richards, Sunrise over Schoodic, early 1870s, gouache on paper, John Wilmerding Collection