Pierrot le fou (1965) presents the adventures of countercultural heroes Ferdinand Griffon (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and Marianne Renoir (Anna Karina). Jean-Luc Godard’s film possesses many characteristics common to pop art, especially the work of three of its greatest North American practitioners: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg. Most pop artworks employed the mediums of painting, print, or sculpture; Pierrot le fou is pop in celluloid. It critiques cinematic conventions, consumer society, and cultural and military imperialism with images in Techniscope and the brilliant hues of Eastmancolor. By sampling and remixing various sources, Godard (b. 1930) brought quotidian, commercial, and political subject matter into the realm of film. The director engaged with the world through the camera lens, omnivorously consuming all manner of subjects and weaving them into a common audiovisual fabric, confounding clear bounds between reality and fiction, acting and action. Revealing his own experimental spirit and an expansion of the definition of cinema, the director stated, "Pierrot le fou is not a film, but an attempt at cinema" that "reminds us one must attempt to live."

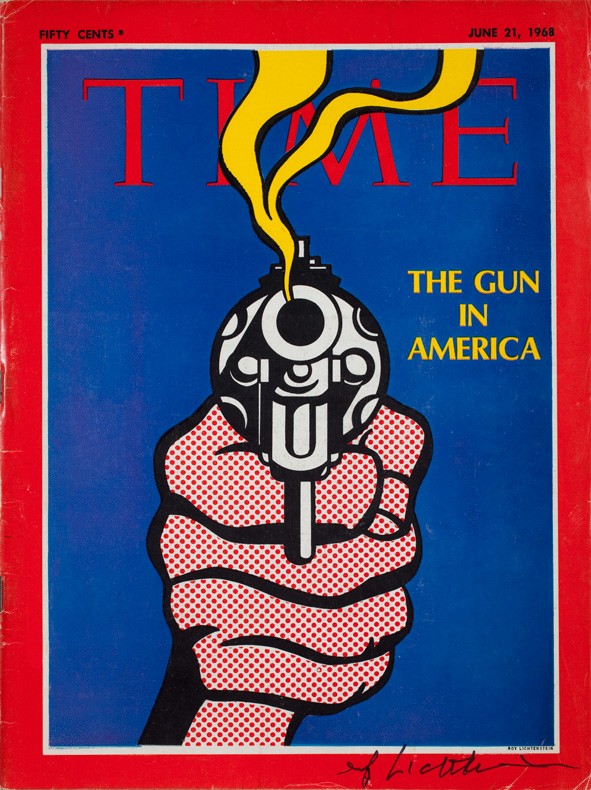

One of pop art’s primary roles, arguably, was to attack the divide between distinct categories of culture. Highbrow and lowbrow intermingle in the oeuvres of many pop artists. Warhol (1928–1987), for instance, mined advertising, newspaper headlines, celebrities, and inexpensive consumer products. He turned these already mediated, popular subjects—which are normally consumed quickly and then often thrown away—into more timeless works of art. Warhol printed on colored canvases. Silkscreen (a commercial technique) collides with painting (a fine art) in his works. We know that Warhol was on Godard's radar, at the very least for his films. In May 1967, Cahiers du cinéma profiled Godard, Alfred Hitchcock, and Warhol, revealing how different pop artists based in the United States worked in similar ways. Oldenburg (b. 1929) asks spectators to reassess consumption by shifting everyday objects—from lipstick to typewriter erasers—into large-scale sculptures. Throughout his career Lichtenstein (1923–1997) also provocatively mixed high and low brows of culture, a basic recipe he marvelously reinvented many times over. Early paintings like

Pierrot le fou is loosely based on Obsession, a 1962 crime novel by the American author Lionel White. For his version, Godard rejects traditional narrative and bends and blurs genres. Although Ferdinand's voiceovers allude to chapter numbers, this literary structure is ultimately subverted as the numerical order of the chapters becomes increasingly hypertrophied and chaotic throughout the movie. The madcap journey Godard represents evokes the conventions of road movies, action thrillers, spy films, and even musicals with dance numbers; he apparently saw Pierrot le fou as an amalgamation and continuation of his prior projects.

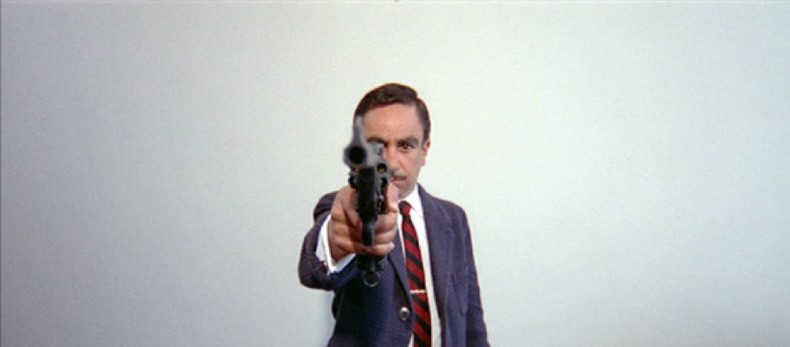

Ferdinand and Marianne's story begins with a chance meeting: Marianne Renoir, Ferdinand's ex-lover, is posing as the niece of his friend Frank (with whom she carrying on an affair); she is enlisted to babysit Ferdinand's daughter while he accompanies his wife, Maria, and friends to a cocktail party at the home of his wealthy in-laws, Madame and Monsieur Espresso. Ferdinand had worked in television, but recently lost his job. His wife hopes that her father can introduce him to a Standard Oil executive at the party who might want to hire him. The reencounter with bohemian Marianne prompts Ferdinand to reject his bourgeois life and its associated rituals, and run away with—or back to—her. But tuning in and dropping out proves to be complicated: Marianne is involved in more dangerous activities than Ferdinand expects. His search for adventure and excitement takes him on a path toward gun-running and deadly intrigue. His transformation from upright citizen to secret agent or revolutionary begins to concretize when, early in the film, Marianne baptizes him with the moniker "Pierrot" as he drives her home. She insists on referring to him by this name, despite his protests. Pierrot is one of the stock characters from the Commedia dell'arte, the tragic and naive clown dressed in white and smitten with the female character Columbine. Marianne’s interpolation seems to work: rather than drop her off, Ferdinand stays the night. From this moment, he veers further and further away from staid Ferdinand and toward the "crazy"(fou) Pierrot.