From the moment photography was first announced in 1839, people were entranced by its ability to stop time and motion. Yet initially slow film and shutter speeds, from a half-second to several seconds, meant that a moving person or object appeared in pictures as a blur, if at all. In the 1870s,

Movement

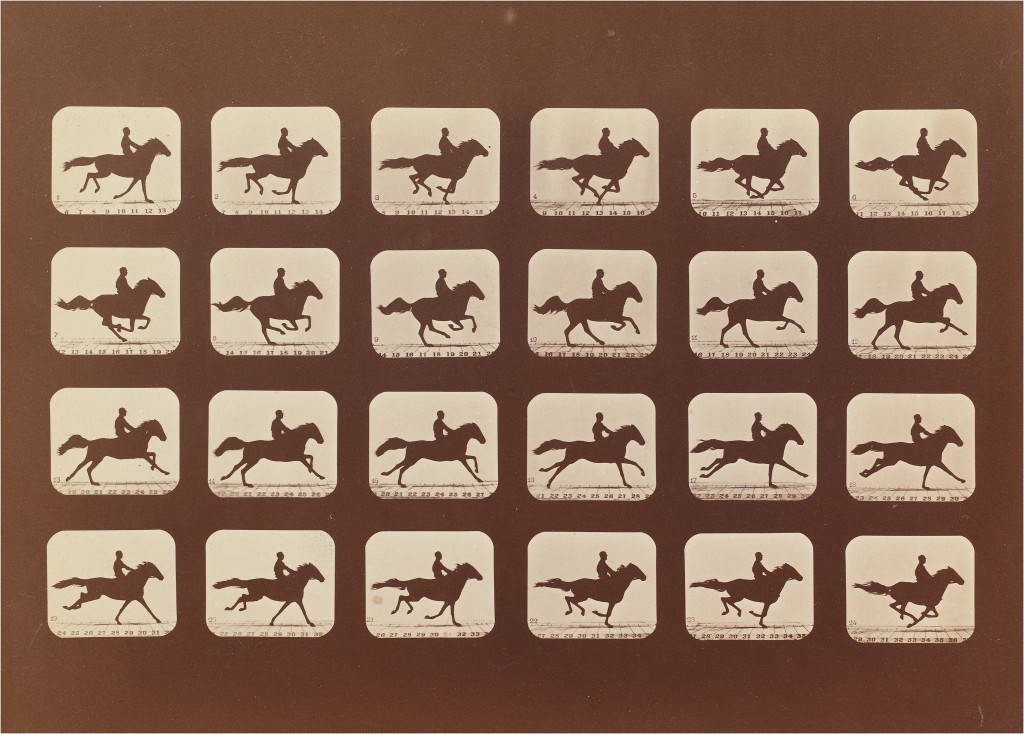

Eadweard Muybridge, Horses. Running. Phryne L. No. 40, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, 1879, albumen print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon 2006.131.7

Harold Eugene Edgerton, Squash Stroke, 1938, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation 1996.146.4

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, other photographers sought to arrest motion for scientific investigations into how and why things move the way they do. Working in France at approximately the same time as Muybridge, the physiologist

Alexey Brodovitch, Untitled, from “Ballet” series, 1938, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Diana and Mallory Walker Fund 2006.71.1

Many other photographers have instead used movement as an important aesthetic tool, recognizing that speed, motion, and new concepts of time are central conditions of modern life. Some arrested motion to infuse their pictures with a sense of a specific time and place. The 1860s British photographer