Overview

Searching for evidence of art ownership can be a challenge that often requires a great deal of sleuthing. Explore some of the documents, records, and stories behind works in the National Gallery’s collection.

Collectors

Beyond the captivating eyes of a Rembrandt van Rijn portrait or the frivolity of a scene by Jean-Honoré Fragonard lie stories of ownership that rival the art itself. Works of art can pass through many hands after leaving the artist’s studio, building a history of ownership referred to as provenance. This often includes a transfer of the artwork between the artist, dealers, collectors, and institutions, acquired through purchase, inheritance, gift, or exchange. But art can move from one owner to another without documentation, creating a gap in provenance. These gaps can represent merely a lack of recordkeeping, but they can also indicate something more nefarious, such as a theft or hidden property.

The search for evidence of art ownership can be challenging. The process requires a bit of good, old-fashioned sleuthing. Sometimes the art lacks a trail of documents that reveal the owner, date and price of purchase, or deed of gift. Fortunately, however, traces of ownership can be found in a multitude of sources, including inventories, sales records, correspondence, labels, collectors’ marks, and notations, as well as in photographs, prints, and albums.

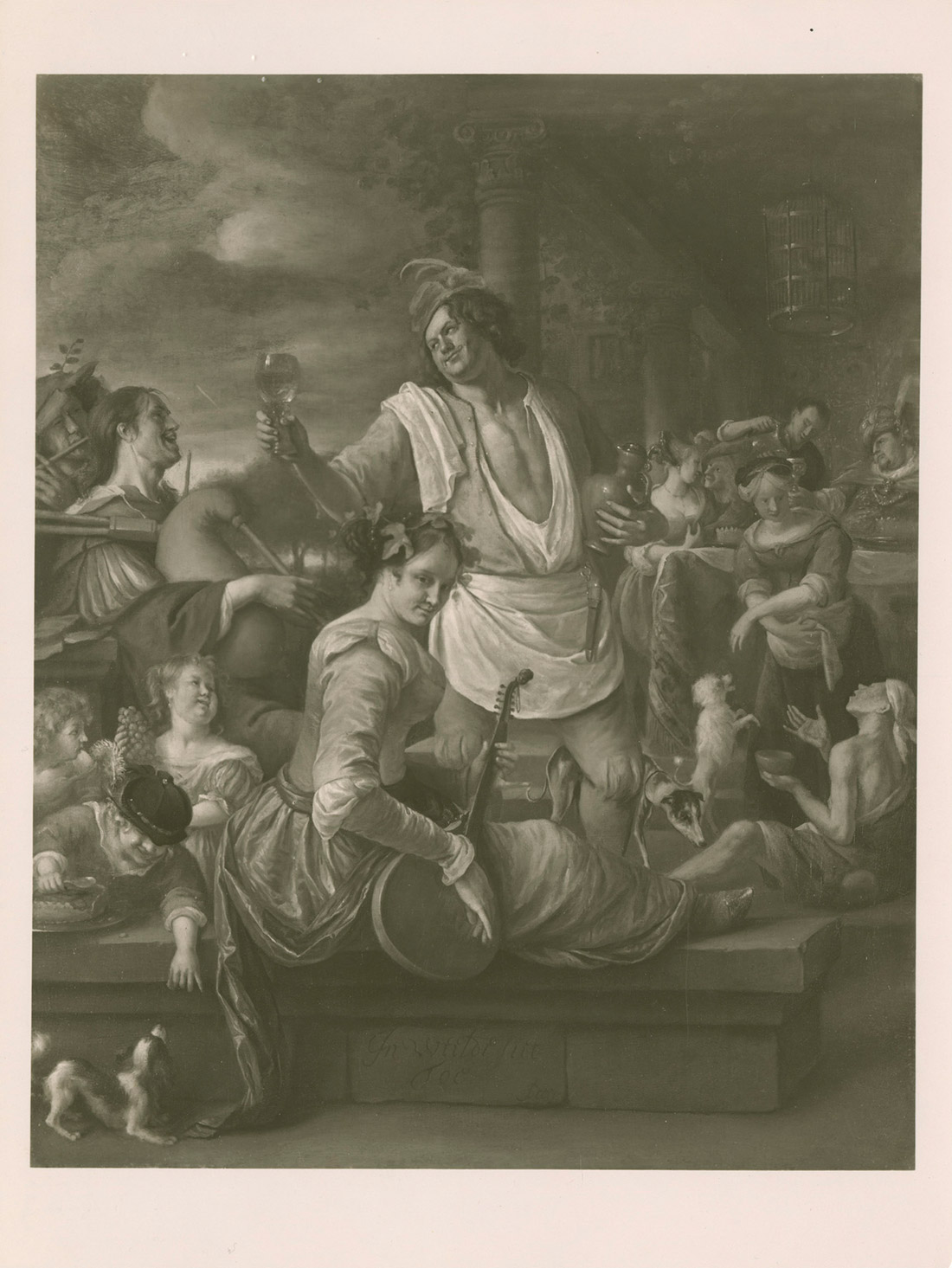

Jan Steen’s Rich Man and Lazarus

With its rich and complex history of ownership, Rich Man and Lazarus or In Luxury Beware, by the Dutch artist Jan Steen (1626–1679), demonstrates how a variety of sources can confirm origin. The composition prominently depicts a reveler in the foreground and the parable of Lazarus and the rich man (Luke 16:19–31) in the background. After leaving Jan Steen’s possession, the painting is next recorded in Amsterdam by 1899 and then with the preeminent Dutch dealer and collector Jacques Goudstikker by 1920. It moves among various Dutch private collectors, and by 1937 it goes from the Dutch dealership D. Katz to the Schaeffer Galleries in New York, and back to D. Katz.

During World War II the firm D. Katz sold art to the Nazis, in some cases in exchange for exit visas for their family members who were desperate to leave the German-occupied Netherlands. These sales are today viewed by many as having been made under duress. In this case, the Steen painting goes from the D. Katz firm to the Goudstikker Gallery on August 14, 1940. However, by this time Goudstikker’s property has been looted by the Nazis, and his gallery is now operated by German banker Alois Miedel. In turn, Miedel sells the Steen painting to the Nazis. By October 17, 1940, the painting is in Adolph Hitler’s personal collection, slated to be hung in the Führermuseum in Linz, a museum that was planned to showcase looted art from across the continent but was never realized.

Unknown photographer, Munich Central Collecting Point Photo of Jan Steen’s Rich Man and Lazarus brought to the National Gallery of Art by Ardelia Hall, Cultural Affairs Office at the US Department of State, specializing in the restitution of Nazi-looted art (1946–1964) and Monuments Woman (MFAA Officer) in Europe (1945), Department of Image Collections

Photographs and documents provide evidence of the processing and redistribution of the Steen painting that occurred at the Munich Central Collecting Point after the war. This includes the Munich inventory number (Munich 4414); the Aussee inventory number given to the painting when the Allies discovered it stored in the Altaussee salt mine toward the end of the war (Aussee 3063); the country of origin and the last owner noted (Holland, Katz); and the date the painting was processed (December 4, 1945).

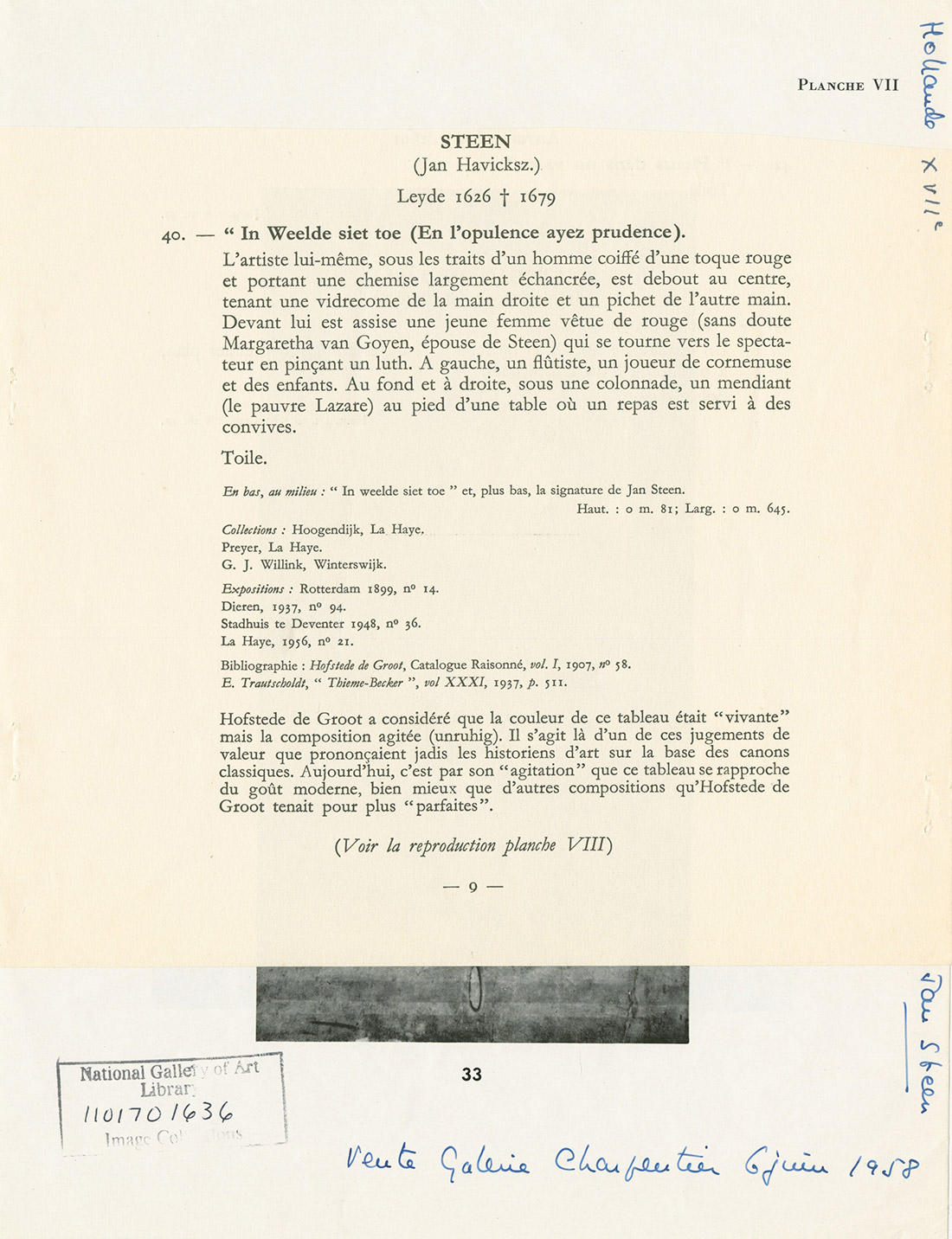

Clipping from Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 1958, with notations by Louvre curator René Huyghe, Department of Image Collections

The painting is restituted to Katz on December 11, 1947. Katz later sells it to a private collector and from there it goes on the art market. By June 6, 1958, it is in the possession of Galerie Charpentier, Paris, documented in these auction catalog clippings bearing notations from Louvre curator René Huyghe. Huyghe’s handwritten notations identify both the dealer and date of sale.

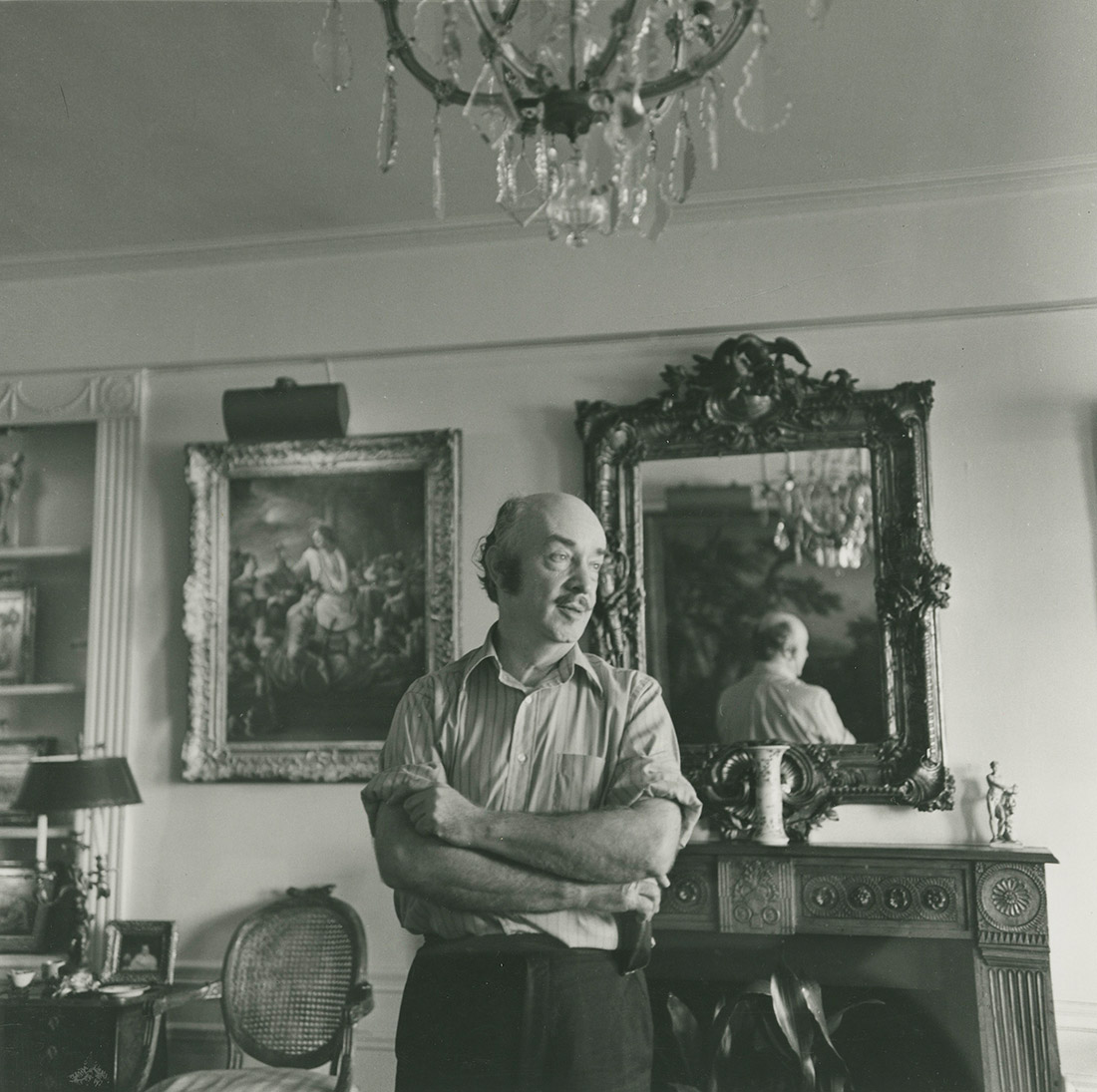

Lida Moser (1920–2014), John Koch with His Painting, Dora at Setauket, and Jan Steen’s Painting, Rich Man and Lazarus, November 22, 1969 (printed 1986), gelatin silver print © Lida Moser Archive, Department of Image Collections

Photographs also can provide evidence of ownership. This photo of the artist and collector John Koch captures him in his living room in New York City on November 22, 1969, surrounded by his art collection. Upon further investigation, the painting hanging to his right is Jan Steen’s Rich Man and Lazarus. This photo was key in determining the ownership of the Steen between 1963 and 1980 and assisting in matters of restitution.

Before the painting was identified in this photo, Koch’s ownership was unknown and the painting’s whereabouts were a mystery for 45 years. The painting eventually became part of the art collection of New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg. Today it is in The Leiden Collection in New York.

Lida Moser (1920–2014), John Koch Seated in His Living Room, 1962 (printed 1986), gelatin silver print © Lida Moser Archive, Department of Image Collections

Antonius Triest, Bishop of Ghent, with His Brother Eugenio

Much like photographs, prints document collecting practices, depicting a collector with their possessions. This print reproduces David Teniers’s painted portrait of Antonius Triest, Bishop of Ghent, pictured in his library with his brother, Eugenio.

Paulus Pontius (1603–1658), after David Teniers the Younger, Antonius Triest, Bishop of Ghent, with His Brother Eugenio, 1653, engraving, Department of Image Collections

Triest commissioned Teniers to paint his portrait in 1652. A year later Paulus Pontius reproduced it as an engraving, making famous Teniers’s original painting of the bishop. Two prominently displayed sculptures, one of Christ Bound and the other of a Penitent Jerome, sit atop the bookcase behind Triest.

Teniers’s inclusion of the sculptures may have emphasized the bishop’s role as an influential art patron and collector. Triest was one of Teniers’s most important patrons, as well as a close family friend. Similarly, Triest was connected to sculptor François Duquesnoy and his brother Jerôme, having commissioned works by both artists.

The sculpture of Christ in Triest’s study, although not identical to the National Gallery of Art’s Christ Bound by François Duquesnoy (2007.67.1), invokes Duquesnoy’s statuettes of the same subject in both form and posture and leads one to question whether these works were in Triest’s collection.

Also of import is the notation on the back of this print. It reads “Charing X Rd 3-6.” This address probably indicates the print’s previous owner on Charing Cross Road in London, most likely one of the many antiquarians in the district.

The print was a gift to the National Gallery of Art from dealer Daniel Katz around 2007 to commemorate his sale, also to the National Gallery, of Duquesnoy’s ivory statuette Christ Bound.

Anna Maria van Schurman

Cornelis van Dalen the Younger (1638–1664), after Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, Anna Maria van Schurman [recto], after 1657, engraving, Department of Image Collections

This portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman, a venerated Dutch savant and women’s education pioneer, was engraved in 1657, reproducing a painting by Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen. Interestingly, the painting, an oil sketch, was intended to serve as a model for the print, the final product, probably produced to commemorate van Schurman’s 50th birthday. There are inscriptions on the front that pay tribute to van Schurman and identify both the painter of the original composition and the print’s engraver.

Cornelis van Dalen the Younger (1638–1664), after Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, Anna Maria van Schurman [detail, verso], after 1657, engraving, Department of Image Collections

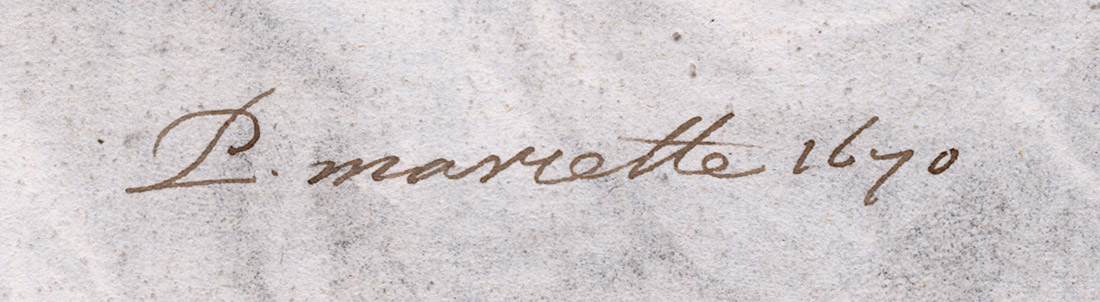

However, if you turn the print over, significant marks on the back provide a compelling piece of the print’s history. A clearly executed signature and date in brown ink in the lower quadrant of the sheet read “P. Mariette 1670,” announcing the owner, Pierre Mariette II. It was common practice for Mariette, collector, engraver, and considered the greatest publisher of the century, to add his monogram.

The signature provides physical evidence, by the hand of the owner, that the print belonged to Mariette and was in his collection by 1670, and later possibly in the collection of his famous Parisian print-collecting and publishing family.

The Mill

Reproductive prints—prints that reproduce another artist’s composition—often bear inscriptions and other marks that convey ownership or a dealer’s connection to the artwork. In some cases, the inscriptions offer insight into the owner’s greater collection.

Alfred-Louis Brunet-Desbaines (1845–1939), after Rembrandt van Rijn, The Mill, P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., 1880, etching, Department of Image Collections

This large print is an etching by Brunet-Debaines after Rembrandt’s The Mill, a painting now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art (1942.9.62). It was commissioned by P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. in 1880, the leading producer of prints after 16th- and 17th-century European paintings and the world’s oldest commercial art gallery. At the time the print was commissioned, the painting was in the collection of Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, the 5th Marquess of Landsdowne, which is clearly inscribed at the bottom of the print.

Producing and disseminating such a high-quality print after the painting may have brought further cachet to the marquess’s collection. Whether the marquess considered selling the painting at the time the print was made is unclear, but it does provide proof of his ownership in 1880.

Dealers

Dealers are important intermediaries in the transfer of art from one owner to another, and in some cases, dealers add the artworks to their personal collections. The records of their trade are an essential piece of the provenance puzzle, revealing sellers, buyers, sales prices, and sometimes the condition of the works of art or historical circumstances at the time of sale.

Existing records from the late 19th century provide a glimpse into one of the strongest art markets in US history, when robber barons and entrepreneurs built significant art collections. Wealthy Americans, in concert with leading dealers, purchased notable art that increasingly came from European collections.

Art Collection Formed by the Late Mrs. Mary J. Morgan

At the end of the 19th century Mrs. Mary Jane Morgan (1823–1885) was one of the most prominent art collectors in the United States and one of New York’s wealthiest women. She began collecting in earnest in the seven years after the death in 1878 of her husband Charles Morgan, a shipping, railroad, and iron tycoon and cousin of J. Pierpont Morgan. She was well-educated, fluent in French, and astute in assembling her collection of European and American paintings, prints, antiquities, porcelain, and decorative arts from a myriad of well-known dealers.

Her collection, containing masterpieces as well as works from up-and-coming artists, was referred to as a “dealer’s collection,” one that rivaled some of the best collections in Europe. She turned part of her New York brownstone into a popular picture gallery where she had private and public showings, causing speculation that she intended to start her own museum. But Mary died unexpectedly on July 3, 1885, without a will, resulting in the sale of her collection for the benefit of her sisters.

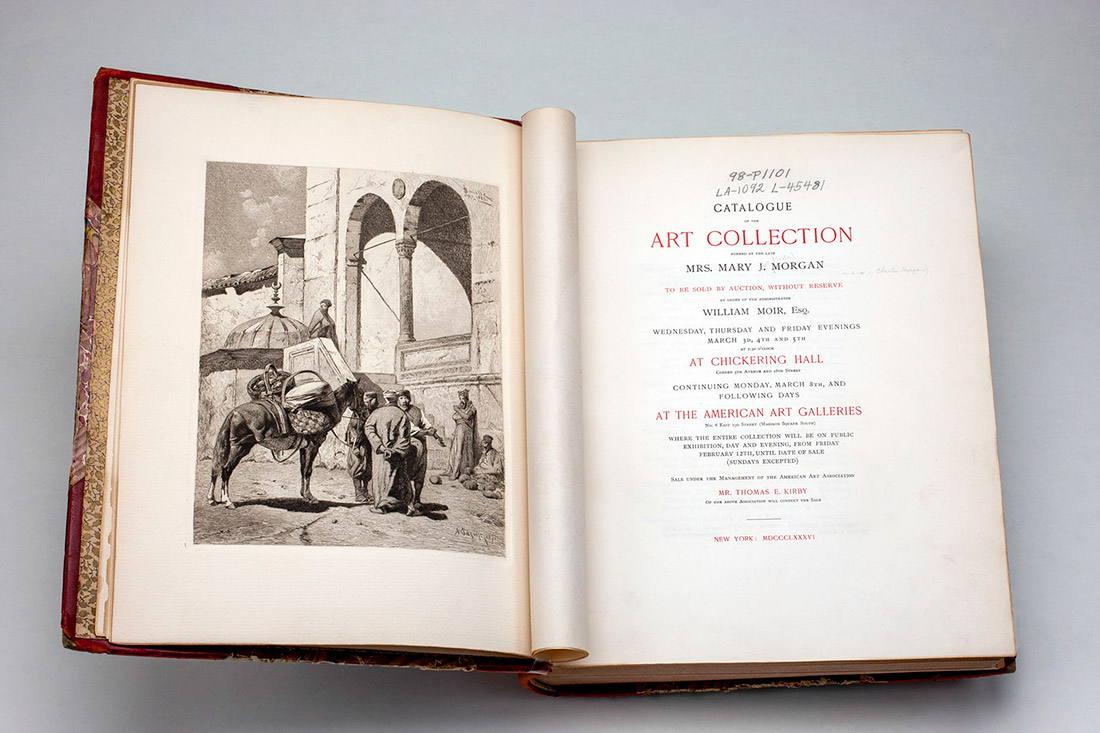

American Art Association, Art Collection Formed by the Late Mrs. Mary J. Morgan, New York, 1886, National Gallery of Art Library

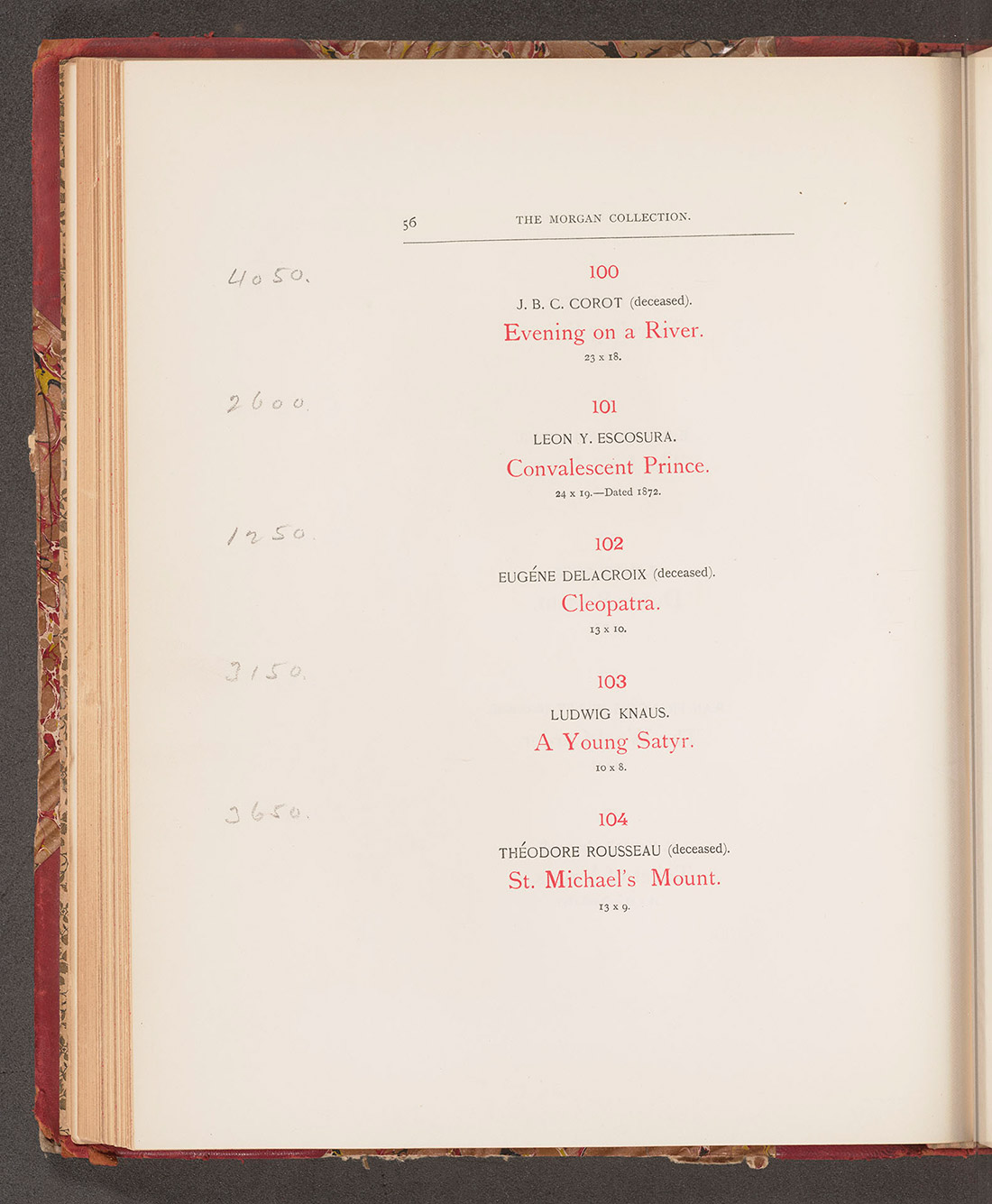

This finely crafted, leather-bound publication is an auction catalog documenting the 1886 sale of Mary’s collection, illustrated with miniature portraits of the artists, photographs, and etchings reproducing works in her collection by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Thomas Moran, among others. The American Art Association, a newly formed but prominent New York auction house, the first in the United States, organized the 13-day sale that took place at Chickering Hall on March 3–15, 1886, with 2,628 lots available for purchase. Next to each lot listed are hand annotations of the hammer price, providing a valuable record of the sales price.

The wide-ranging treasures from Mary’s collection are now in private and public collections across North America and Europe, including the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Walters Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

American Art Association, Art Collection Formed by the Late Mrs. Mary J. Morgan, New York, 1886, National Gallery of Art Library

There is a collector’s sticker on the inside cover of this auction catalog indicating that it was once in the library of Joseph Widener, whose father, Peter A. B. Widener, purchased artworks from Mary’s collection years after the sale. Joseph later gave those works to the National Gallery.

Frost & Reed Inventory Book

Established in Bristol in 1808, Frost & Reed is one of England’s oldest dealerships, initially specializing in the sale of works on paper, and later, paintings. By the turn of the century, they expanded to London, taking their moniker from Walter Frost and William Reed, and by 2002 across the Atlantic to New York.

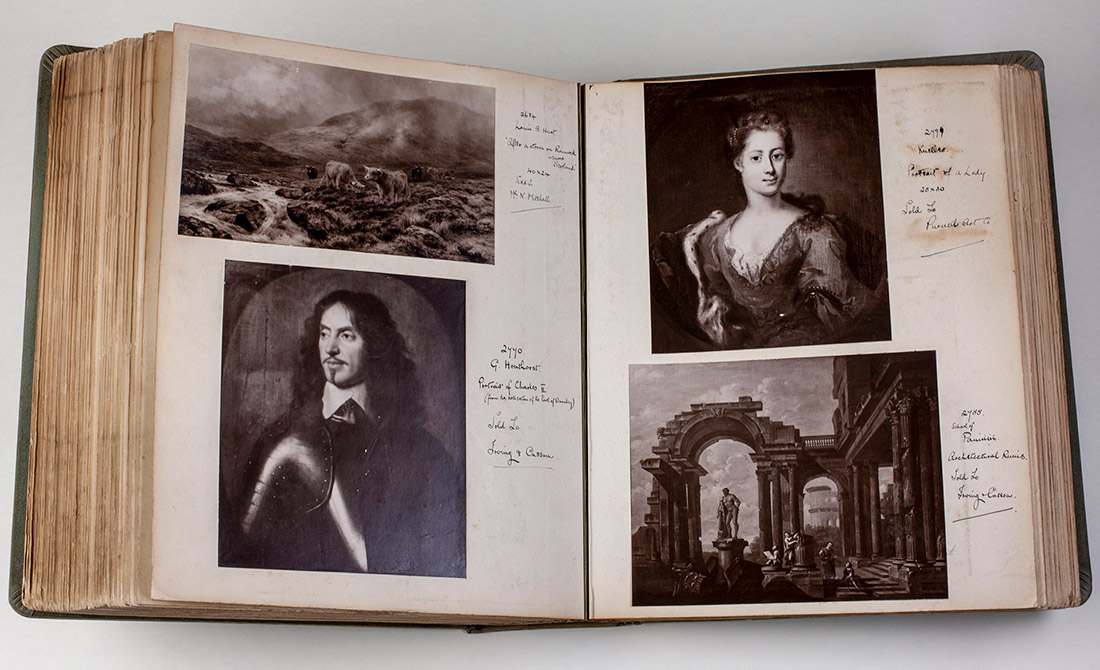

Frost & Reed Inventory Book, Company Records, May 1924-May 1927, Department of Image Collections

The National Gallery’s Department of Image Collections has Frost & Reed company records between 1900 and 1948, which include mounted photographs and reproductions of paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs by artists such as John Singleton Copley, Joshua Reynolds, Gerard van Honthorst, Jacob van Ruisdael, Godfrey Kneller, Henri Fantin-Latour, Thomas Lawrence, Canaletto, Henry Raeburn, and others that were sold by the dealer.

The inventory books with photos of their stock and hand annotations of attribution, inventory number, name of buyer, sale date, and in some cases, copyright information constitute an important record of ownership, potentially filling gaps in provenance.

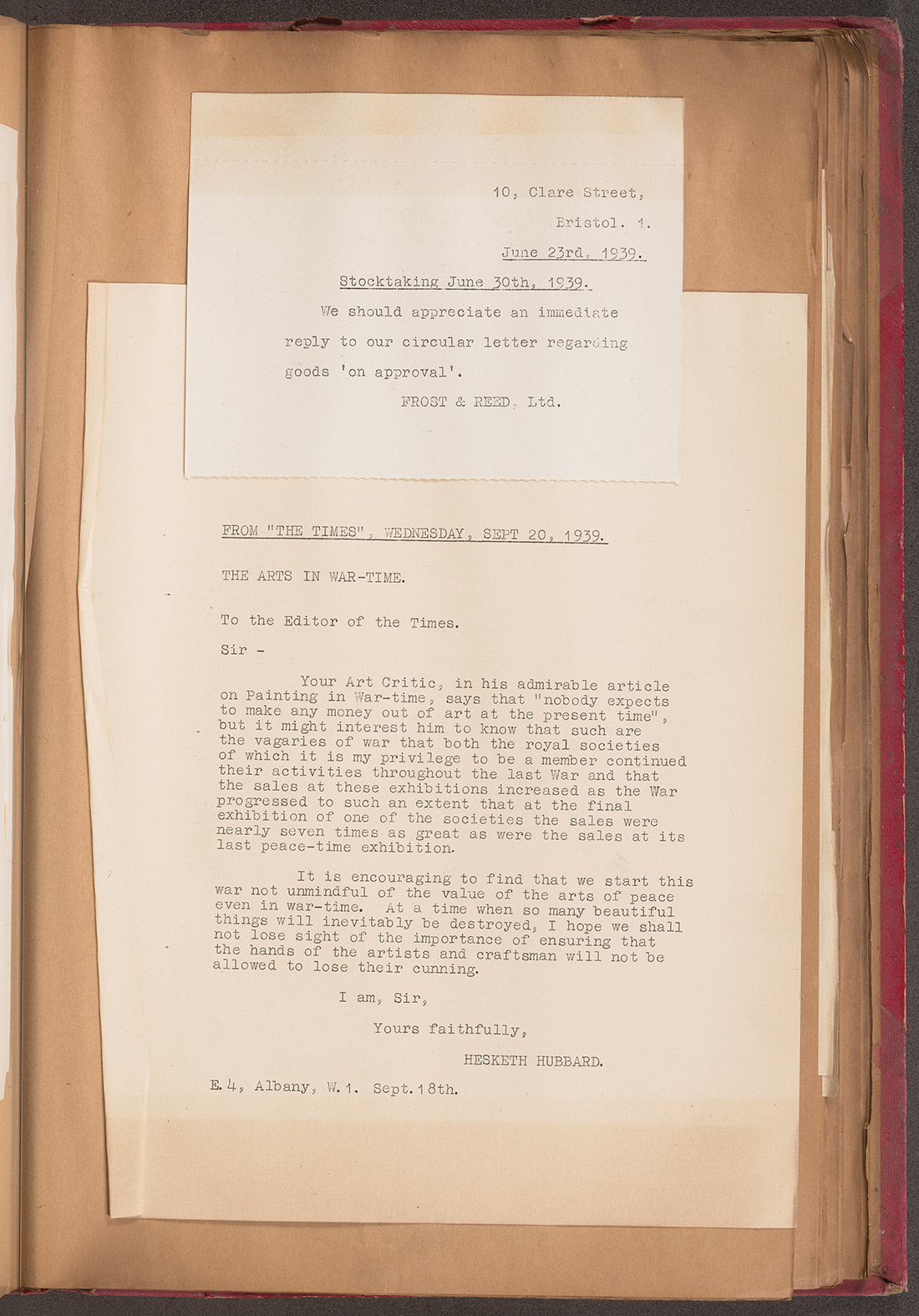

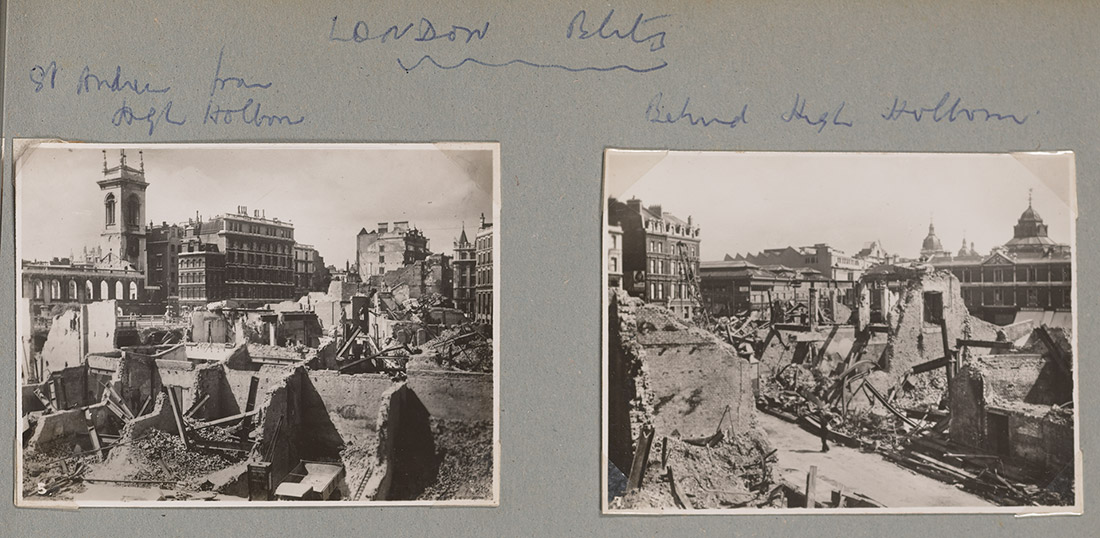

London Blitz

Some of the most interesting company documents from 1936 to 1944 relate to the fate of the art market at the beginning of World War II. A transcription from a letter to the editor of the London Times, dated September 20, 1939, laments that artworks will “inevitably be destroyed” in the war that had just been declared days earlier on September 1.

Frost & Reed Circulars, 1936–1944, Department of Image Collections

The letter is probably a template meant to inquire with owners regarding their works on consignment and asks them if they wish to insure these against “War Risks.” This was a timely consideration, given that London was heavily bombed starting on September 7, 1940, including the West End, where Frost & Reed is located.

The London Blitz photographic album provides a sense of the damage and destruction London endured.

Photochrome Co. Ltd., London Blitz, Turnbridge Wells: Photochrome Co. Ltd., 1941?, gelatin silver prints, Department of Image Collections

Photochrome Co. Ltd., London Blitz, Turnbridge Wells: Photochrome Co. Ltd., 1941?, gelatin silver prints, Department of Image Collections

Sam Salz

Sam Salz (1894–1981) was one of the most eminent dealers and collectors of impressionist art in the United States from the time of his arrival in New York. Salz had a well-trained eye, having studied art and art history at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna as well as in Paris. Around 1920, while still in Paris, he transitioned from artist to art dealer, working for the famed contemporary French dealer Ambroise Vollard. Shortly thereafter Salz opened his own dealership in Cologne and went on to sell art in Brussels and London.

His dealings in modern art led the Nazis to put Salz on their list of individuals selling “degenerate art.” In 1938 Salz escaped the rising Nazi tide in Europe, moving to New York and opening his eponymous gallery, which he eventually operated out of his townhouse on East 76th Street. His business flourished in part due to his previously established reputation in Europe and England, and possibly because he bought only artworks that he “admired.” After World War II, Salz used his knowledge and connections in the art market to assist the Commission of Reparation return stolen property.

In addition to museums, Salz had many influential clients, including National Gallery of Art patron Paul Mellon, Henry Ford II, David Rockefeller, Dr. Albert Barnes, Walter Annenberg, Greta Garbo, Orson Welles, Vladimir Horowitz, and one of his closest friends, fellow émigré and author Erich Maria Remarque, who also fled the Nazis. Salz had personal ties to artists, such as Chaïm Soutine, Marc Chagall, and Henri Matisse, purchasing their work directly from them.

Unknown photographer, Diego Rivera, Edward G. Robinson, and Sam Salz in Rivera’s San Francisco Studio, 1940, digital print from negative, printed 2022, Gift of Marc Salz in memory of his father, Sam Salz, Sam Salz Archive, Department of Image Collections

The photograph pictures Sam Salz visiting his friend Diego Rivera’s San Francisco studio, where Rivera was painting actor and Salz client Edward G. Robinson, who was posing for Rivera’s Golden Gate International Expo mural.

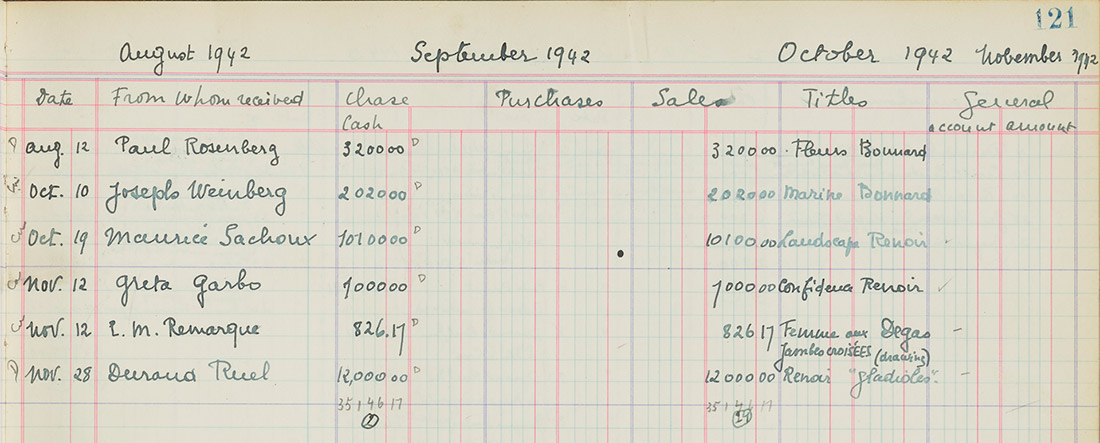

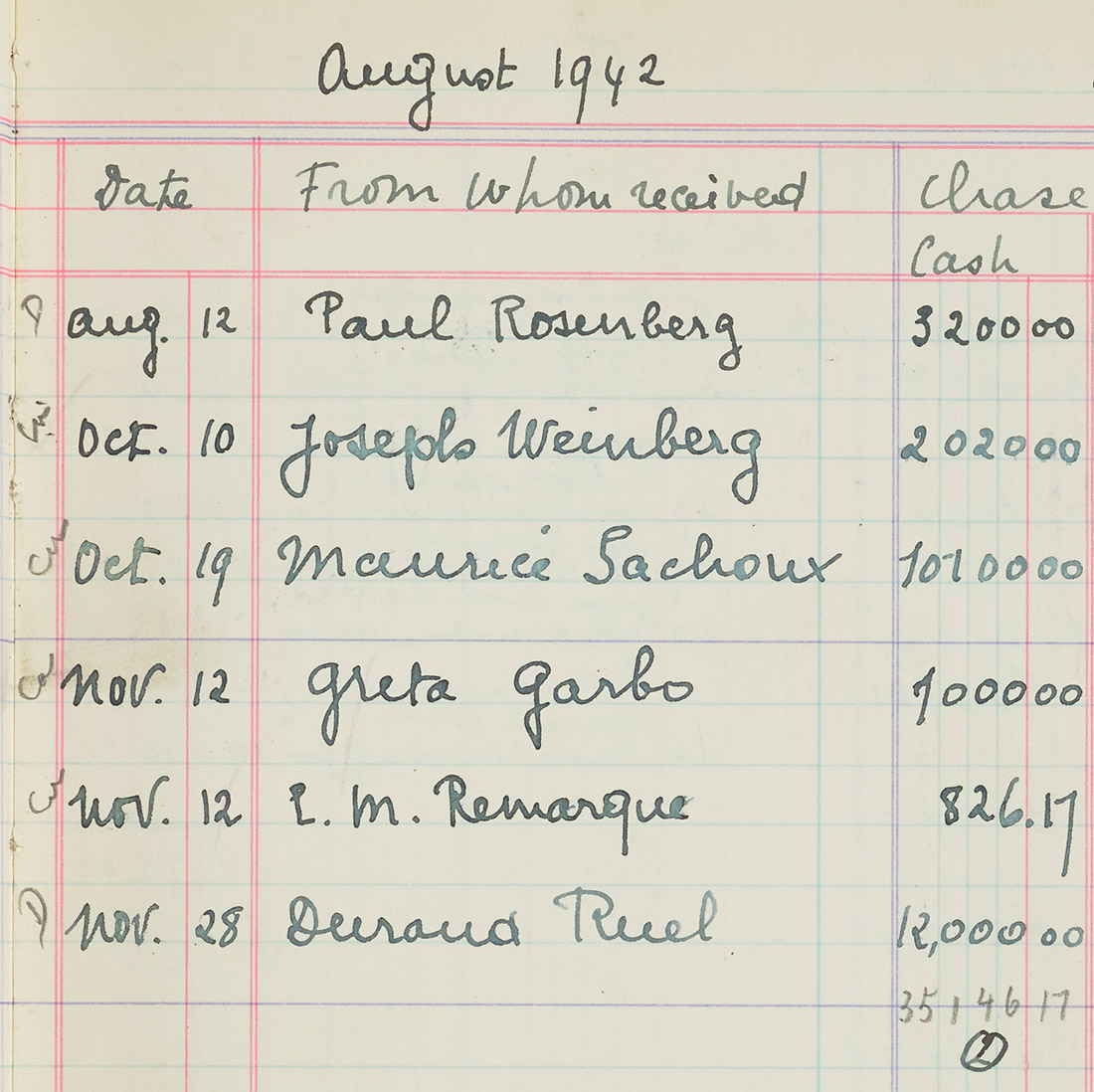

Sam Salz Inventory Book, 1939–1945, Gift of Marc Salz in memory of his father, Sam Salz, Sam Salz Archive, Department of Image Collections

Sam Salz Inventory Book [detail], 1939–1945, Gift of Marc Salz in memory of his father, Sam Salz, Sam Salz Archive, Department of Image Collections

This inventory book, a gift from Sam’s son Marc, represents the inventory, sales, and expenses at his dealership between 1939 and 1945, the most fulsome records from 1940 to 1944. These inventory records are extremely valuable because they provide evidence of ownership and sales during the war years and Salz’s early business in the US.

Jack Wasserman, Sam and Marina Salz, c. late 1940s–1950s, gelatin silver print, Gift of Marc Salz in memory of his father, Sam Salz, Sam Salz Archive, Department of Image Collections

Around 1941 Salz married dancer Marina Franca, and from roughly that period she assisted in keeping the books. The stylistic differences in the handwritten entries imply that there were various bookkeepers maintaining this inventory book, probably including Marina.

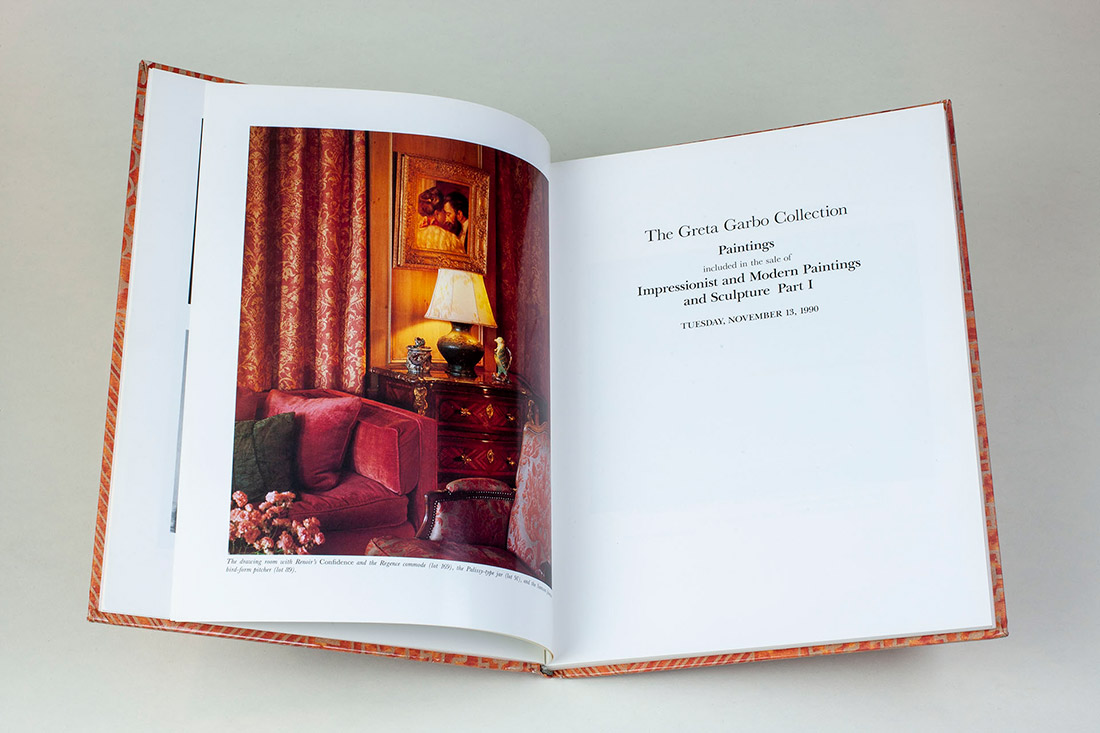

Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo (1905–1990) was one of many illustrious clients who purchased art from Sam Salz. Garbo’s full name is notated in this inventory book on November 12, 1942, having purchased Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Confidence for $7,000. Salz’s close friend, author Erich Maria Remarque, is listed on the line below Garbo as purchasing an Edgar Degas drawing, Femme aux Jambes Croisées, for $826.17 the same day.

It is unclear exactly how Greta Garbo became acquainted with Sam Salz, but he did mingle with the Hollywood set and spent time in Los Angeles cultivating business with both private clients and institutions, such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Garbo, also a European émigré, probably became acquainted with Salz through Remarque. The three would discuss art, play cards, and reflect on war-ravaged Europe.

Clarence Sinclair Bull (1896–1979),

This photograph is part of a major gift of 700 distinguished photographs from Mary and Dan Solomon to the National Gallery of Art. Of those, 400 are press photographs, including this headshot of Greta Garbo in a golden headdress, a publicity shot for her starring role in the 1931 hit film Mata Hari. This image demonstrates how press photographs could be manipulated—in this case with the application of gray and black ink, blocking out Garbo’s shoulders and chest and making her face and hands more prominent, particularly emphasizing her piercing gaze.

Sotheby’s, The Greta Garbo Collection, New York, 1990, National Gallery of Art Library

Images from Sotheby’s 1990 sale of Greta Garbo’s collection capture the interior of her New York City apartment, where Confidence, the Pierre-Auguste Renoir painting she purchased from Sam Salz, can be seen. It is one of many impressionist works in her collection.

Scholars and Experts

Art and its attributions can be called into question, leaving us to wonder if it is in fact by the hand of the master. Confirming authorship requires a deep understanding of an artist’s body of work. Best practices dictate that scholars and other experts conduct rigorous study to substantiate their opinions.

The assessment of a work’s attribution and date involves the careful examination of a large sample of work within, and outside, an artist’s oeuvre. Scholars and experts then document their opinions in correspondence, publications, and on photographs that can be given to collectors, dealers, and museums for verification and future use. These photographs are often signed and dated, validating the authenticity of the document.

Dr. Max J. Friedländer

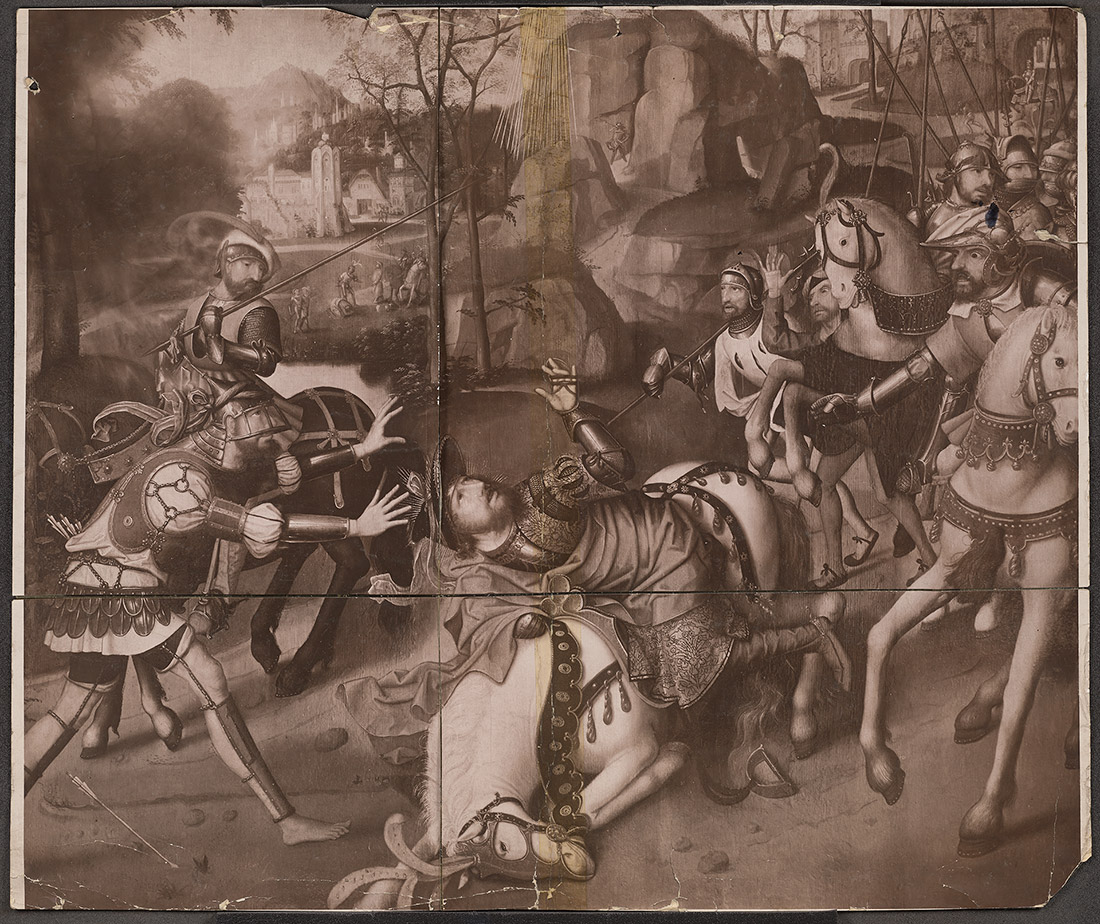

Dr. Max J. Friedländer (1867–1958), Jean Bellegambe’s Painting, The Conversion of St. Paul [recto], with Notation by Dr. Max J. Friedländer, 1926, gelatin silver print, Department of Image Collections

German scholar and curator Dr. Max J. Friedländer took this photograph of Jean Bellegambe’s sizeable panel painting, The Conversion of St. Paul (1520s), probably during one of his European travels studying paintings in private collections. Friedländer crafted this oversize image by stitching together four separate photos from four quadrants of the composition, unifying them with cellulose tape, the only technology he may have had available. It was a creative solution that allowed him a greater overview of the painting. Once the photo was folded up, it became portable and fileable. Some of Friedländer’s photos went to dealers or other scholars, offering his views on attribution, condition, and ownership, but most were ultimately the foundation for his personal photographic archive.

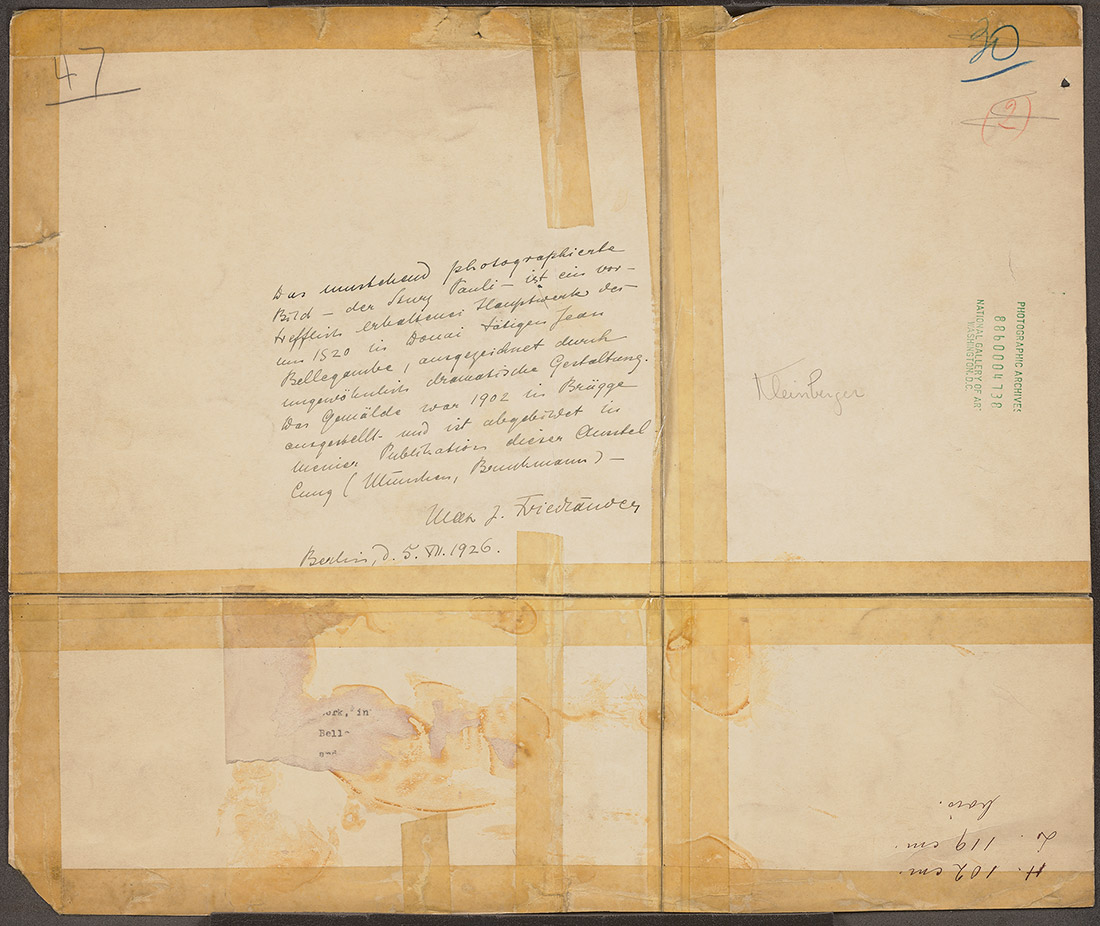

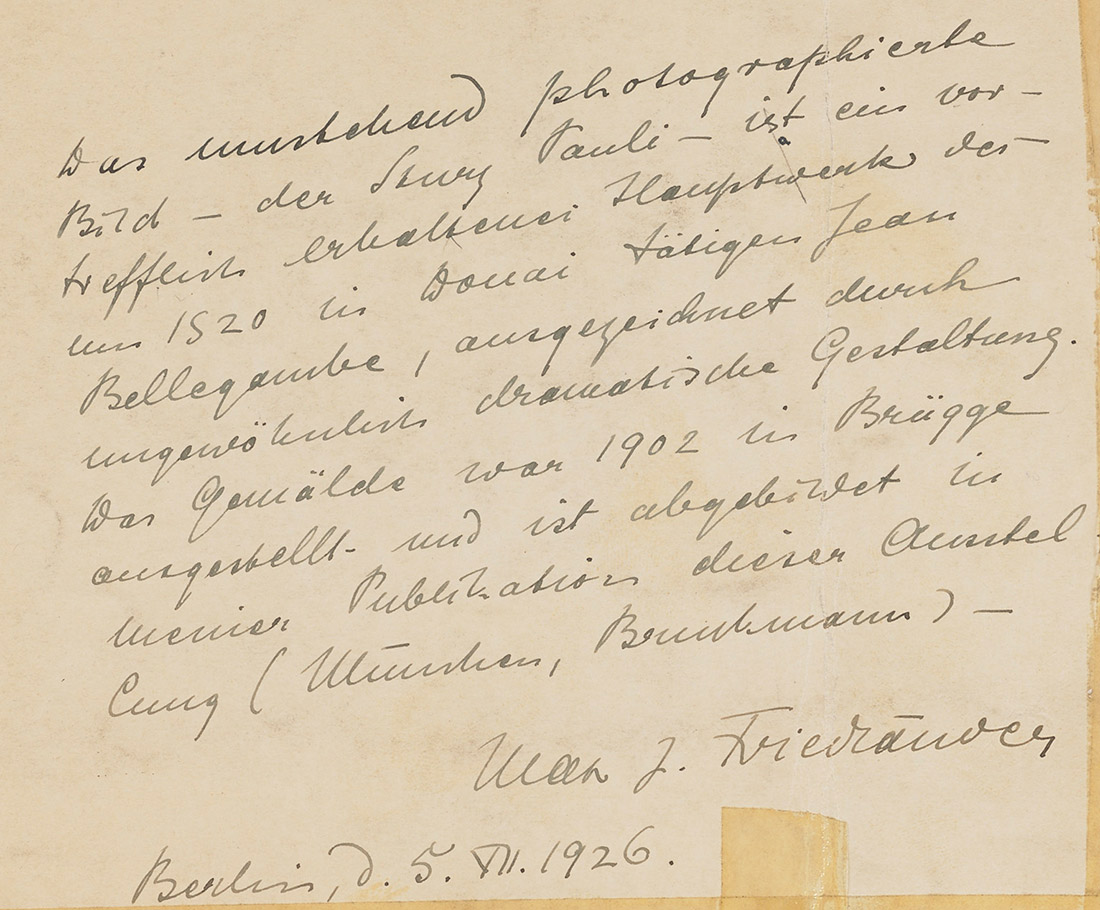

Dr. Max J. Friedländer (1867–1958), Jean Bellegambe’s Painting, The Conversion of St. Paul [verso], with Notation by Dr. Max J. Friedländer, 1926, gelatin silver print, Department of Image Collections

On December 5, 1926, while in Berlin, Friedländer made significant notations on the back of this photo. By this time, he was director of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum and was a highly respected scholar of Northern Renaissance painting. Dealers, collectors, and scholars alike would have been interested in his professional opinion. His notations, in German, identify the artist, subject, and date of the painting, mention that it was exhibited in Bruges in 1902, and included in his exhibition publication in 1903. The Bellegambe painting went on the market in 1927. Friedländer’s notations confirming its attribution may have served as authentication before it was offered for sale.

Dr. Max J. Friedländer (1867–1958), Jean Bellegambe’s Painting, The Conversion of St. Paul [detail, verso], with Notation by Dr. Max J. Friedländer, 1926, gelatin silver print, Department of Image Collections

Nina Kandinsky

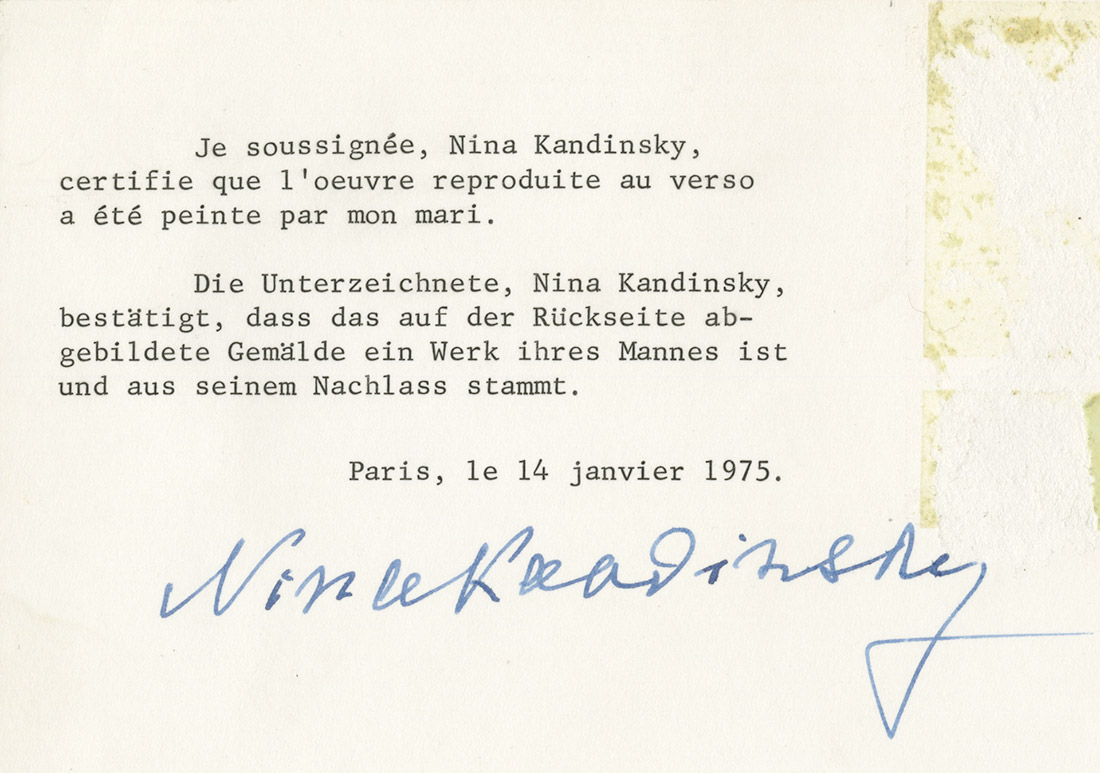

Jean Dubout, Wassily Kandinsky’s Painting, Murnau: Houses on the Obermarkt [detail, verso], with Notation by His Wife, Nina Kandinsky, 1975, gelatin silver print, Department of Image Collections

This black-and-white photograph of Wassily Kandinsky’s polychromatic painting Murnau: Houses on the Obermarkt depicts the main street in Murnau, a town in the Bavarian Alps where he and his partner, artist Gabriele Münter, summered in the early part of the century. Kandinsky did not sign or date this painting, but its abstract, Fauve-inspired style are characteristic of his work around 1908.

The painting was uncovered after Kandinsky’s death when his widow, Nina, found it wrapped in a Munich newspaper dated 1908, further solidifying the painting’s execution date. Interestingly, this work was not included in the inventories the artist made of his paintings. In charge of his estate, Nina may have been asked to substantiate the attribution and date of the painting by providing signed certification that it was part of her late husband’s oeuvre. With her statement, written in French and German, and signature on the back, Nina attests that the work of art depicted in the photograph was painted by her late husband. The painting is now in the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Madrid. The 1977 inventory number indicates that it entered the collection two years after Nina’s certification. The photograph likely served to authenticate the painting prior to its sale.

Exhibitions

Artworks often come from far and wide to fill the walls of an exhibition and remain there temporarily. Forms of ephemera such as photographs and albums commemorate exhibitions and later serve to document the special assemblage. The images and inventories generally provide the title and date of the artwork, as well as the collections they belonged to at the time of the exhibition. The identification of collectors is particularly useful because it is not out of the ordinary for art that remains in private hands to go unrecorded for periods of time.

Gems of the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester, 1857

Caldesi and Montecchi (firm), Gems of the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester, 1857, P. & D. Colnaghi

With its 16,000 works of art, Manchester’s Art Treasures of Great Britain is the largest exhibition to have been mounted in the United Kingdom and possibly the world. The exhibition ran from May 5 to October 17, 1857, and showcased art from private collections, including the exhibition’s patrons, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. There was a wide range of works on display: British and European painting, watercolor, works on paper, sculpture, decorative arts, and the arts of Asia, arranged in chronological order.

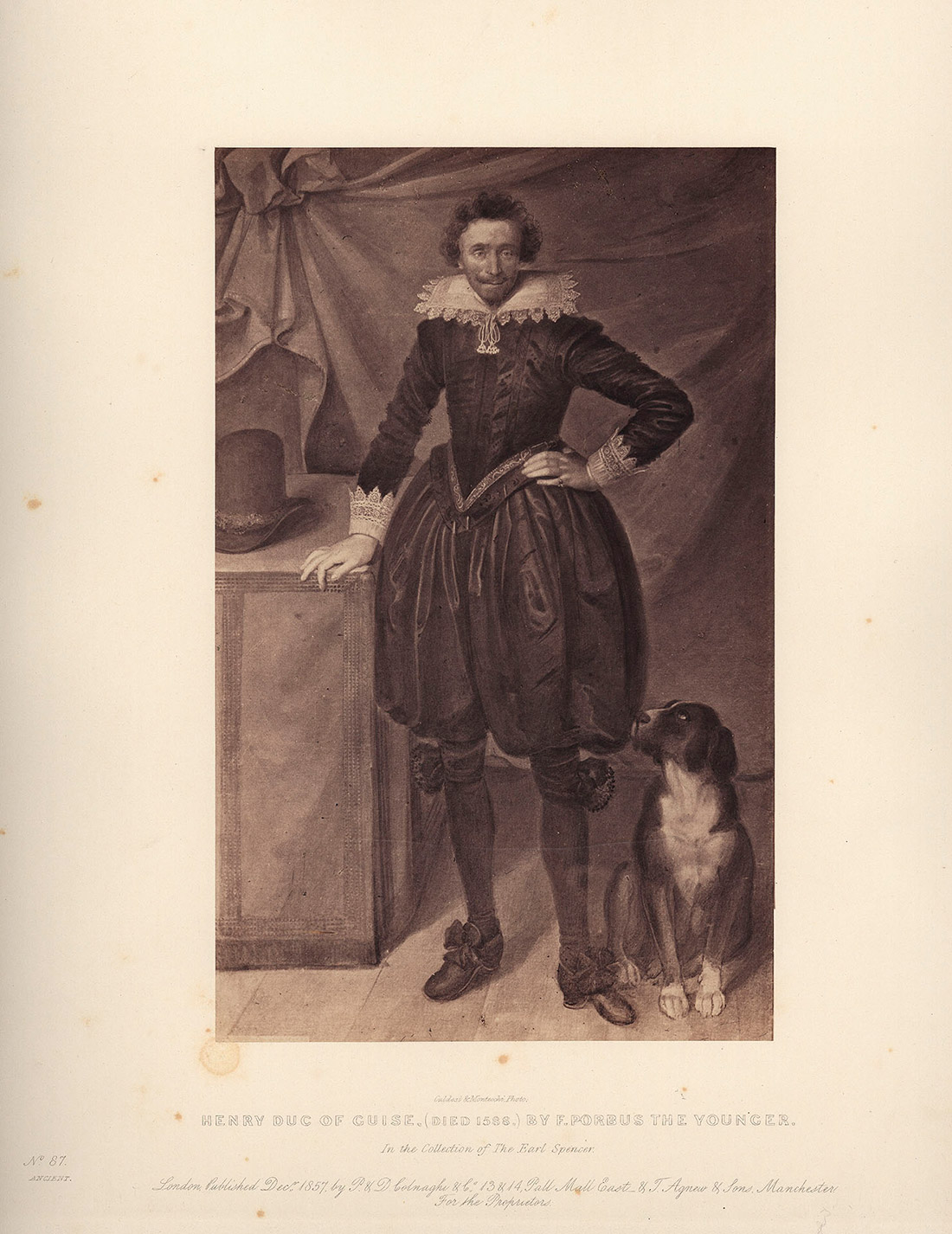

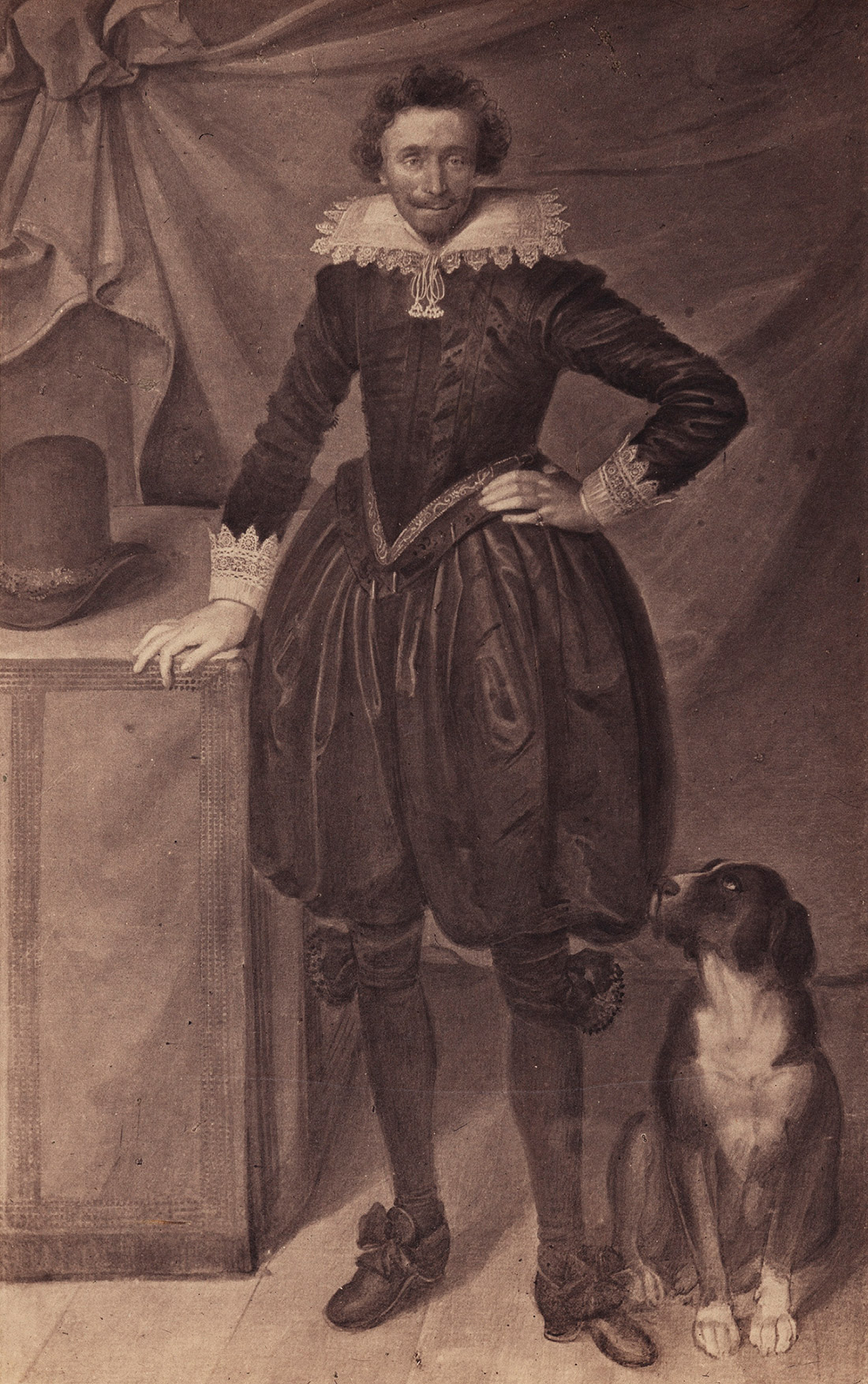

Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Chevreuse

Manchester T. Agnew and Sons, publisher, Frans Pourbus the Younger Painting, Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Chevreuse, 1858, albumen silver print, Department of Image Collections

This photograph of Frans Pourbus the Younger’s portrait of Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Chevreuse, is part of a photographic album assembled to commemorate and document some of the most popular works exhibited. Of particular interest is the painting’s title at the time of the exhibition. The sitter is incorrectly identified as Henri, Duc de Guise, which was later described as “an impossible identification” due to the date of the portrait. It is most likely Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Chevreuse, the second son of the Duc de Guise, whose life dates agree with the painting’s inscription. Changes in title are an important part of a painting’s history and can be essential in tracing its provenance.

Manchester T. Agnew and Sons, publisher, Frans Pourbus the Younger Painting, Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Chevreuse, 1858, albumen silver print, Department of Image Collections

The Pourbus portrait belongs to the Earl Spencer and is part of the collection at Althorp, one of England’s most stately manor homes. Althorp is the ancestral home of the Spencer family, where one of its best-known inhabitants, Lady Diana Spencer, lived before becoming Princess of Wales.

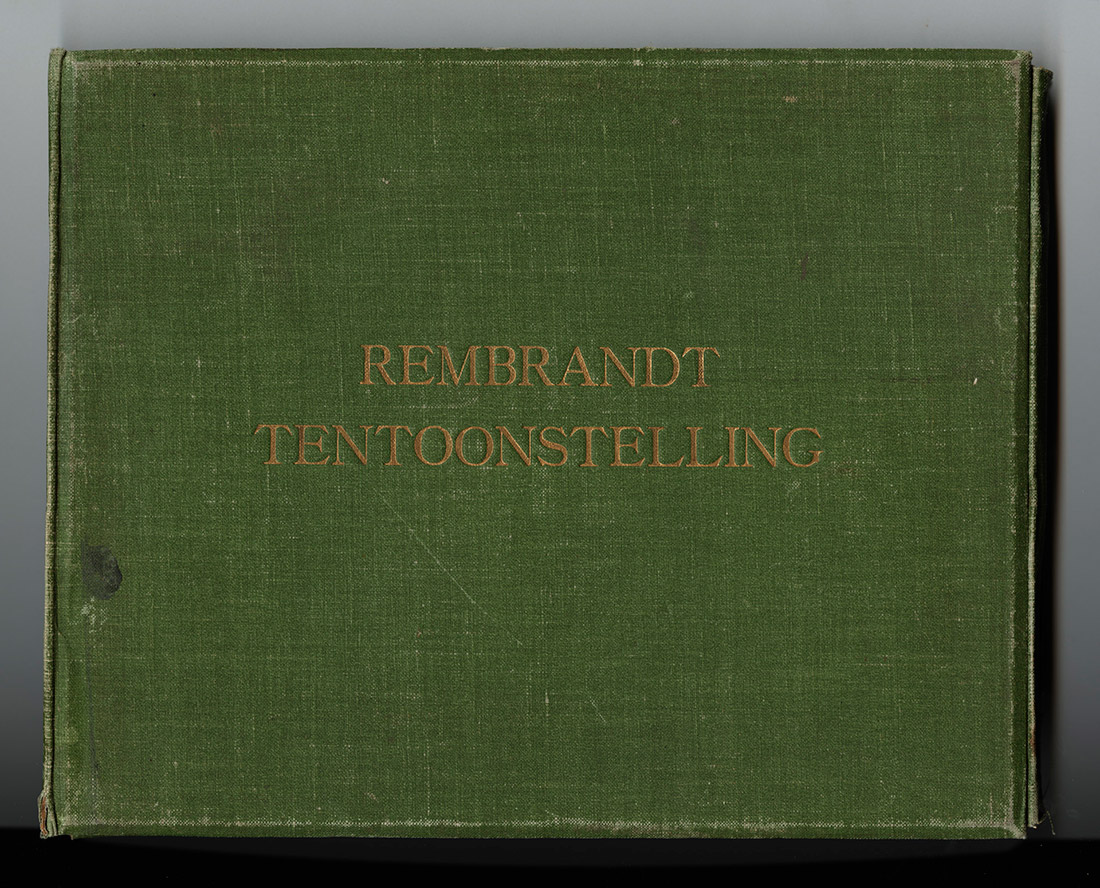

Rembrandt Tentoonstelling (Rembrandt Exhibition)

Rembrandt Tentoonstelling (Rembrandt Exhibition) album cover, Department of Image Collections

This photographic folio highlights the preparations and installation of the Rembrandt exhibition that took place in Amsterdam from September to October 1898, commemorating the coronation of the Netherland’s new queen, Wilhelmina. The ambitious exhibition was an homage to both the queen and Rembrandt, consisting of 124 paintings and 350 drawings and etchings from collectors across Europe and England, including German Emperor Wilhelm II, England’s Queen Victoria, private collectors, and museums. The show’s curator, Hofstede de Groot, envisioned that the monographic exhibition would be a triumph, bringing together a substantial representation of Rembrandt’s work: “The Dutch could have paid no nobler homage to their young queen and her coronation than by bringing together a collection of the masterpieces of the greatest painter to whom Holland has given birth.”

Transfer of The Night Watch from the Rijksmuseum to the Stedelijk for the Rembrandt Exhibition, Department of Image Collections

Rembrandt’s monumental canvas, The Night Watch, pictured in transit across the Museumplein from the Rijksmuseum to the Stedelijk Museum, had to be shoehorned in through a window.

View of Room 27 with Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves and Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-Feather Fan, 1898, silver collodion print on board, Department of Image Collections

Four paintings currently in the National Gallery of Art’s collection were featured in the exhibition, among them the two pictured here, Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves and Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-Feather Fan, which can be seen through the doorway, hung together. At the time of the Amsterdam exhibition, the pendant pair were in the collection of the Yusupov family in St. Petersburg, Russia. The photographs, in combination with inventory lists from this exhibition, provide an important record of ownership from 1898.

You can see these and other works in The Art of Sleuthing exhibition at the National Gallery Library through September 23.

Suggested Reading

Braun, Karel. Alle tot nu toe bekende schilderijen van Jan Steen (Rotterdam, 1980).

Garlick, Kenneth. A Catalogue of Pictures at Althorp (Glasgow, 1976).

Hofstede De Groot, Cornelis. De Rembrandt tentoonstelling te Amsterdam: 40 photogravures met tekst (Amsterdam, 1898).

Quodbach, Esmée. What's Mine is Yours: Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States (New York, 2021).

Salz, Marc. Sam Salz blog: http://samsalz.blogspot.com/

Saxon, Wolfgang. Sam Salz Art Dealer and Collector of Impressionist Works, Dies at 87, New York Times, March 22, 1981.

Vergo, Peter. Entry on Wassily Kandinsky’s Murnau: Houses in the Obermarkt, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional: https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/kandinsky-wassily/murnau-houses-obermarkt

Zorach, Rebecca, Paper Museums: The Reproductive Print in Europe, 1500–1800 (Chicago, 2005).

Banner detail: Clarence Sinclair Bull (1896–1979), But There Was a Day When One Woman Was Enough; Her Name Was Garbo. She Didn’t Have to Take Her Clothes Off., 1931 (inked 1932), reproduction of gelatin silver print with applied color, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon, 2018.177.291