Born 1904, Lee City, Kentucky

Died 1984, Campton, Kentucky

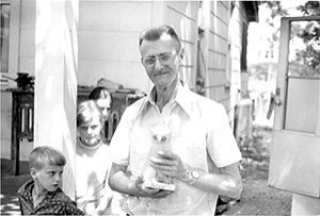

Edgar Tolson’s austere wooden figures, around twelve inches tall, all have distinct personalities, thanks to his careful delineation of details such as eyebrows, fingers, and even the soles of shoes. Tolson learned woodworking through farm labor: building barns and fashioning wagons and yokes. He was born to sharecroppers in Wolfe County, Kentucky, where he spent his whole life. As a boy, he carved wooden bowls, spoons, and locomotives—an activity he called “whittling.” Requiring nothing more than a pocketknife and a piece of wood, whittling was a popular pastime in the rural south. Tolson did not carve regularly until after a stroke in 1957, when, determined to regain strength in his hands, he began to make canes, animals, and dolls, which he gave away to friends.

Tolson’s woodcarvings reached a wider audience through the Grassroots Craftsmen cooperative, established in 1966 by VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) to promote economic advancement in Appalachia. The Grassroots Craftsmen sold his figurines at the Smithsonian Institution museum shops and the Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen fairs. Faculty in the University of Kentucky art department discovered Tolson’s dolls at a guild fair in 1967 and became enthusiastic collectors of his work. John Tuska, a ceramics professor, suggested to Tolson that he tackle more complex figure groups and the nude, leading to his first compositions of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. It was for sculpture professor Michael Hall and his wife, Julie, that the artist carved his most ambitious work: the Fall of Man series, an eight-part tableau telling the stories of Adam and Eve and their sons Cain and Abel.

While Tolson’s single figures are rooted in a local tradition of wooden dolls known as “Kentucky poppets,” his depictions of Adam and Eve recall nineteenth-century carvings of the subject by self-taught artists such as Wilhelm Schimmel. Perhaps the popularity of Tolson’s biblical scenes is due in part to their evocation of emblematic examples of American folk art. But he also brought his own experience to the subject. His father was a preacher, and he did some preaching himself, though he also served time in prison for deserting his family and was drawn, as his brother recounted, to “whisky, women, cares of the world.”[1] Tolson’s religious scenes are poignant images of human frailty.

Antonia Pocock

[1] Quoted in Ardery 1998, 19.

Ardery, Julia S. The Temptation: Edgar Tolson and the Genesis of Twentieth-Century Folk Art. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.