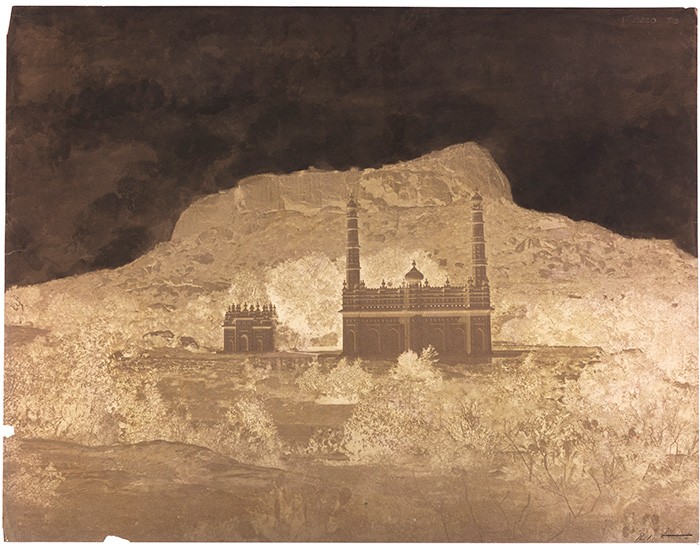

Photographers in the 19th century often retouched their negatives to compensate for the fact that photographic emulsions were not equally sensitive to all colors of the spectrum. For example, if the negative was properly exposed to capture foreground details, the sky would often appear faded and blotchy. To achieve a balance between the two, some photographers painted the sky in their negatives with pigment so that they could create an even tone when printing it (see works by Louis De Clercq and Dr. John Murray in the slide show below).

Exhibition Catalog Captain Linnaeus Tripe

Roger Taylor, Crispin Branfoot, with Sarah Greenough and Malcolm Daniel

AudioIntroduction to the Exhibition, lecture by Sarah Greenough, exhibition curator

Audio Symposium Lecture Part 1: ''A Glorious Galaxy of Monuments': Photography and the Archaeological Survey of India after Tripe," John Falconer

Audio Symposium Lecture Part 2: "Interpreting Early Photography in India: Medium and Method," Zahid R. Chaudhary

Audio Symposium Lecture Part 3: "Measuring Time: Linnaeus Tripe’s Inscription of the Thanjavur Temple, 1858," Maria Antonella Pelizzari

PDF Download Public Symposium Program

Photographic Practices of the 1850s

When Tripe began to photograph in the early 1850s, the medium was still a handcrafted process. Photography was not yet industrialized, and the inconsistent quality of materials forced photographers to adjust their own chemical formulas to achieve their desired results. Tripe primarily chose to make his negatives on paper rather than on glass, because paper negatives were more portable when he was traveling long distances and easier to use in the extreme heat and humidity of India. He also used a recently introduced waxed-paper process to make his negatives more transparent and produce greater detail.

Linnaeus Tripe, Royacottah: Eedgah and Tomb, December 1857–January 1858: (fig. 1) left: waxed-paper negative (note applied pigment in sky; click image to zoom in), Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford; (fig. 2) right: positive print, Private Collection, Washington, DC

Fig. 3. Linnaeus Tripe retouched his negatives based on models such as James Duffield Harding’s lesson on drawing oak trees, c. 1850, lithograph, Private Collection

Fig. 4. Detail from a waxed-paper negative by Linnaeus Tripe of Belloor: Temple of Vishnu, Bimanum, with Ammanovara Temple, Munduppums, and Dweepastumbum, December 1854 (note applied pigment on leaves), Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford

Tripe retouched his negatives more extensively and dexterously than most 19th-century photographers. To convey different kinds of clouds and other atmospheric effects, he learned how pigment when applied to a negative would translate into its reverse tonality when printed (figs. 1 and 2, at top). While correcting overexposed foliage, he followed the example of art teachers who advocated the use of short strokes to mimic the appearance of leaves (figs. 3 and 4).

Examples by Tripe's Contemporaries: