Alonso Berruguete was a revolutionary force in the arts of sixteenth-century Spain. Born around 1488 in a small town in the Kingdom of Castile (now central Spain), he spent his youth at the side of his father, the accomplished painter Pedro Berruguete. Around the age of eighteen, he made the life-altering decision to relocate to Italy, where he spent the next decade absorbing the lessons of the Italian Renaissance. On returning to Spain, he was invited to serve as court painter to the new king, Charles I (the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). Shortly after, he decided to branch out into the more lucrative field of sculpture. His focus became retablos, the often monumental painted and sculpted altarpieces traditionally installed in Spanish churches.

Introduction

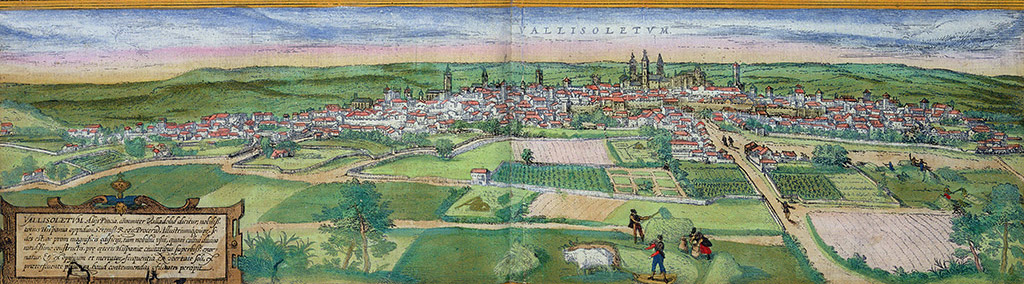

Church of San Benito el Real, Valladolid, Spain

Fig. 1: Reconstruction of the retablo mayor of San Benito el Real, Valladolid. Photo: Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. The outlined works on this reconstruction of the altarpiece of San Benito are on view in the exhibition Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance from October 13, 2019 to February 17, 2020. Areas in gray have been lost.

Alonso Berruguete specialized in retablos—vast, multistory wooden altarpieces encompassing architecture, sculpture, and painting. With their expressive figures and elaborate decoration in gilding and color, these towering monuments conjured visions of heaven inside the churches of Renaissance Spain. Berruguete completed his greatest retablo for the monastery of San Benito el Real in the city of Valladolid. Although the altarpiece was dismantled in the 19th century, its original appearance can be reconstructed from the surviving sculptures and paintings. Tiers of gilded niches housed figures of Saint Benedict, the Virgin Mary, and Christ, as well as narrative reliefs, paintings, Old Testament prophets and patriarchs, and soldiers and sibyls inspired by designs of

This exhibition features numerous elements from the retablo of San Benito. Close examination of the works on view reveals how Berruguete and his workshop fashioned the immense multimedia ensemble. In addition, several documents record the original commission and conditions for the project, which was begun in 1526 and completed in 1533.

Fig. 2: View of Valladolid from Civitates orbis terrarum, by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, with plates by Joris Hoefnagel, 1582, hand-colored engraving, private collection. Photo: The Stapleton Collection/Bridgeman Images

Creating the Retablo

First trained as a painter, Berruguete shifted his focus to the traditional Spanish form of wooden retablos in his mid-20s. The construction of these large, complex altarpieces required the participation of carpenters, joiners, painters, wood-carvers, and other specialists. The first step in the creation of the altarpiece was the development of a master design, known as a muestra rasguñada, which would guide the work of the various craftsmen. It showed the architectural elements, sculpted figures, and paintings. Although no such plan survives for the San Benito commission, a document of March 1527 reveals that Berruguete was required to make one. His drawing likely depicted the overall structure of the retablo and its wooden ornament, and designated the major figures and narrative reliefs.

Carving and Joining

Fig. 3: Alonso Berruguete, Old Testament Prophet (Isaiah?), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Fig. 4: Alonso Berruguete, Old Testament Prophet (Isaiah?) (from behind, showing addition of two pieces of wood to the figure), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Fig. 5: Alonso Berruguete, Old Testament Prophet (Isaiah?) (detail of the base and underside of the left foot), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid.

Each sculpture on the retablo was carved from numerous pieces of wood that were then joined together. The figure of an Old Testament prophet with voluminous draperies and a windswept beard was fashioned in several stages. The artist, or a carver (entallador) under his supervision, joined two long pieces of wood to form the prophet’s bent torso. Then a third length of wood was attached at the figure’s lower right side to create the leg and drapery. Two oblong wooden pieces were added to the middle of his back, which was left mainly unfinished and would have been hidden when the sculpture was placed in its niche. Similarly, the underside and base of the left foot are composed of three separate wooden parts, as seen in the photo above.

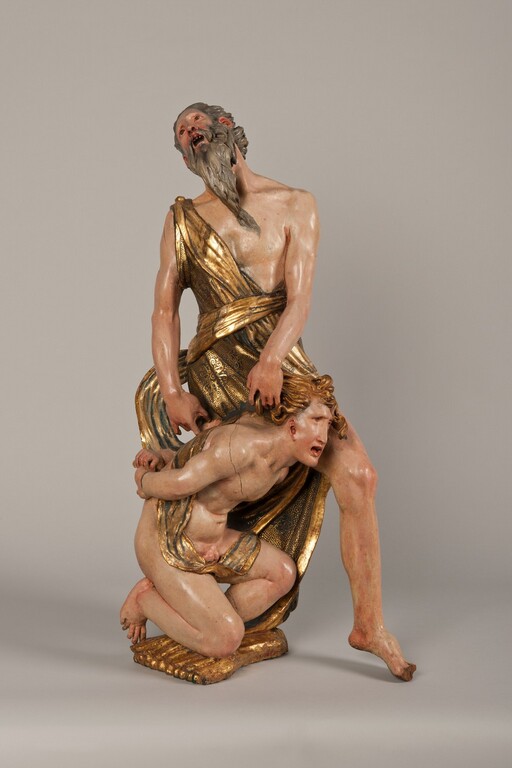

Fig. 6: Alonso Berruguete, The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Berruguete’s additive approach was unusual. By compiling different sections of wood as his sculptures progressed, he forged expressive and dramatic designs that were not limited by the physical properties of a single block. The daring group of The Sacrifice of Isaac achieves emotional force through the projecting left leg of Abraham, the broad loop of drapery emerging from his right side, and the crouching figure of Isaac.

Fig. 7: Alonso Berruguete, The Sacrifice of Isaac (detail of dowel on the left side of the head of Isaac), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid.

The artist joined the various pieces of wood with glue and dowels. One of these dowels appears on the left side of Isaac’s head. It was probably used to attach an extra wooden curl to the mass of hair already carved on the head, and became exposed when the curl was separated from the sculpture.

Fig. 8: Alonso Berruguete, The Sacrifice of Isaac (detail of the underside of Abraham’s right foot showing application of glue-soaked cloth to the wooden sculpture, tucked under the heel), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid.

In addition to dowels, cloths soaked in glue were used to cover the joins between pieces of wood. Some of these cloths remain visible on the underside of the foot of the patriarch Abraham. As the wood of the sculpture shrank and expanded with differences in temperature and humidity, the cloth prevented the attached pieces from shifting out of place. Dowels and strong fabric were the preferred means to attach the wood together; iron nails were sometimes used but might corrode and eventually would have caused the wood to crack.

Draperies

Fig. 9: Alonso Berruguete, Saint Christopher, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Fig. 10: Alonso Berruguete, Saint Christopher (detail of drapery composed of fabric and glue), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Fig. 11: Alonso Berruguete, Saint Christopher (detail of drapery from behind), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Some of the figures’ garments were carved out of wood, while others were fashioned from additional cloths soaked in glue. The figure of Saint Christopher holds a bit of his clothing in his right hand. This element is composed of real fabric: on the back of the sculpture, the textured fabric is visible, along with some of the extra cloth held back by the hand. This technique was a clever and easy way for Berruguete to form animated passages of drapery.

Preparation for Gilding and Painting

Fig. 12: Alonso Berruguete, Reconstruction of a pediment with soldiers, sibyls, and grotesque decoration, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

Fig. 13: Demonstration image of the application of preparatory layers for painting: gesso (left) and bole over gesso (right). Photo: National Gallery of Art conservation division

After the carving and assembly of the sculptures came the process of gilding and painting their surfaces. The first step in this procedure was to coat the wood with gesso, a substance made of animal glue mixed with plaster, which provided a preparatory base for the application of paint and gold. Two layers were applied: yeso grueso, or coarse gesso, followed by yeso mate, fine gesso.

On top of the gesso, a workshop assistant applied layers of bole, consisting of iron-rich clay mixed with animal glue. This formed a hard, smooth surface for applying and burnishing gold leaf. The final layer of bole, which would receive the gold, was carefully polished.

Gilding and Estofado

Fig. 14: Demonstration image of the application of gold leaf: unburnished (left side) and burnished (right side). Contrary to the appearance of this zoomed in view, when observed from a distance, the right side shines brightly while the left side remains dull. Photo: National Gallery of Art conservation division

Next came the application of gold leaf. The bole was dampened with water to soften the glue, and individual leaves of gold were carefully floated on the surface using a gilder’s brush. The gold was gently tapped to expel any air bubbles. Once it had dried, the gold layer was polished with a burnishing stone. The demonstration image shows gold leaf unburnished at left and burnished at right.

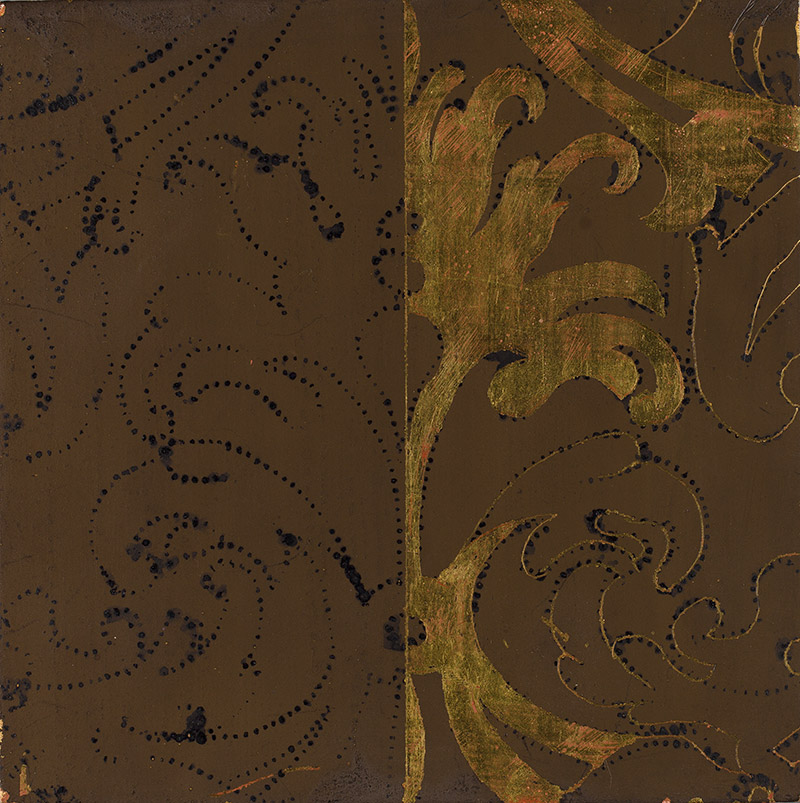

Fig. 15: Demonstration image of estofado technique: tempera paint applied over gold leaf; patterned design transferred to the paint surface (left); paint scraped away within the pattern to reveal underlying gold (right). Photo: National Gallery of Art conservation division

Fig. 16: Alonso Berruguete, The Sacrifice of Isaac (detail of estofado on Abraham’s clothing), 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

In a technique known as estofado, the gold surface was brushed with thin layers of egg tempera paint. After the paint had dried, a patterned design was sketched freehand on the surface, or transferred from a template. Then, the areas of paint within the design were carefully scraped away to reveal the gold leaf beneath. This process (also known as sgraffito in Italian) created elaborate patterns of gilded decoration in imitation of cloth brocade.

Fields of elaborate estofado appear throughout the San Benito altarpiece, particularly in the garment of Abraham in the sculpture of the Sacrifice of Isaac. Here the craftsman carefully scraped out the scrolled patterns freehand. Irregular forms are visible in the design, as with the paired scrolls that do not match. Because the estofado would be viewed from afar under low light, there was no need for geometric precision.

Encarnación

Fig. 17: Alonso Berruguete, Crucified Christ, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

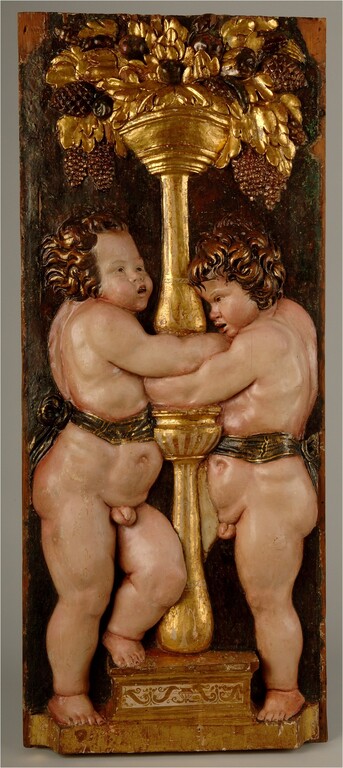

Fig. 18: Alonso Berruguete, Relief with Putti, 1526/1533, painted wood with gilding, Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid. © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain), photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor

The final step in decoration of the surface was to paint the areas of encarnación, or flesh tone of the figures. First a layer of lead white paint was applied over the preparatory gesso, followed by a coating of animal glue. This helped to give the oil paint a high polish. The tones of skin, facial details, and hair were carefully painted, with pink glazes added to areas such as cheeks, knees, and knuckles.

A document of 1527 specifying the conditions for making the San Benito altarpiece obliged Berruguete to paint all the hands and faces of the figures himself. Still, he must have delegated large parts of this extensive task to assistants, while closely supervising the quality of the finished sculptures.

The encarnación marked the final step in the production of this monumental retablo. On November 27, 1532, Berruguete wrote to a colleague that he had finished work on the altarpiece and was delighted with the results: “Señor, I have completed the work in San Benito . . . and it is of such perfection that I am enormously content.”

Related Exhibition

Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain

October 13, 2019 – February 17, 2020

West Building, Main Floor, Galleries 72, 73