Frederick Sommer in Context

EXPERIMENTS IN ABSTRACTION

Frederick Sommer, Drawing, 1950, tempera, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Frederick Sommer

Drawings in the Style of Musical Scores

Sommer’s belief that beautiful forms are intrinsically logical and meaningful is, perhaps, best exemplified by the so-called “drawings in the style of musical scores.” By his own recollection, in 1934, Sommer was struck by the formal appeal of manuscript musical scores that he saw on display in Los Angeles. Eventually, he became convinced that “only the really great composers . . . are the ones who have good looking scores.”[1] In response to this insight, throughout the 1950s Sommer created numerous drawings that loosely resemble musical notation. He eventually asked two musician friends, Stephen Aldrich and Walton Mendelson, to “perform” the drawings for the first time in 1968.

Frederick Sommer, Drawing, 1955, tempera, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Frederick Sommer

Frederick Sommer, Paracelsus, 1957, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Frederick Sommer

Cameraless Negatives

In the 1950s, Sommer started to experiment with cameraless negatives. He drew with soot and grease on glass or squeezed paint with his hands between sheets of cellophane, as in Paracelsus, creating prints by letting light pass through the resulting patterns onto sensitized paper.[2] The technique was reminiscent of decalcomania, Max Ernst’s way of creating unusual textures by laying a sheet of paper or glass on a painted canvas and pulling it away while the paint was still wet.[3] The procedure Sommer invented used the photographic process to capture the textures of paint as light passed through it. Sommer named the torso-like shape that he conjured Paracelsus, after the Renaissance doctor, alchemist, and mystic who made great contributions to experimental science and medicine while seeking hidden, occult knowledge. The fascination with Paracelsus forms yet another link between Sommer and the surrealists, who considered the alchemist to be a forefather and published a group of his apocalyptic woodcuts accompanied by prophetic dream interpretations in the second issue of the journal VVV.[4]

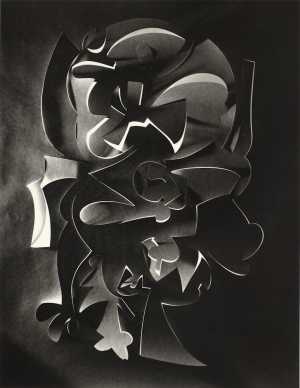

Frederick Sommer, Cut Paper, 1980, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Frederick Sommer

Sommer’s long-standing interest in bringing together photography and drawing resulted in the series of Cut Paper photographs he created starting in 1962. These were backlit photographs of abstract forms that Sommer brought to life by quickly slicing lines with a knife on large sheets of previously rolled up paper. After being scored and suspended, the sheets, which still had some curl in them, became three-dimensional drawings full of suggestive shapes and dramatic shadows.[5] Though Sommer eventually gave up photography in the mid-1980s, when he was no longer able to work in the darkroom, as late as 1983 he still said of his artistic practice, “I tried not to give up painting, not to give up drawing, not to give up making musical scores. I tried to figure out ways in which all these things could be preliminary moves to become a photograph.”[6]

[1] Quoted in Lyons and Cox, The Art of Frederick Sommer, 219.

[2] Rule and Solomon, Original Sources, 183.

[3] Spies and Rewald, Max Ernst. A Retrospective, 100.

[4] For more on the surrealists’ interest in Paracelsus, see Alyce Mahon, “The Search for a New Dimension: Surrealism and Magic,” in Amy Wygant, ed., The Meanings of Magic from the Bible to Buffalo Bill (Oxford and New York, 2006), 221–234.

[5] Sommer’s process of creating the cut “drawings” is described in detail in Philadelphia College of Art, Frederick Sommer, 14.

[6] Quoted in Lyons and Cox, The Art of Frederick Sommer, 228–229.