The belching smokestacks and effluents of industry transformed the marine and land vistas of England. Work, too, was transformed as laborers toiled in continuous shifts to meet the demands of a growing economy and population for fuel and other raw material. The changes wrought in English life by industrialism intrigued Turner and captured his imagination. Yet, the effects of nature equally enthralled the artist.

The River Tyne winds across northeast England to the North Sea, passing through the city of Newcastle, just a few miles from the river’s mouth. The site of vast coal mines, as well as the manufacture of glass and iron, Newcastle was at the fulcrum of the Industrial Revolution by the turn of the 19th century. Pictured here is the River Tyne at Shields, a town downriver from Newcastle proper. Coal mined nearby was loaded at Shields onto small flat-bottomed vessels called keels. The keels were navigated across the shallow river and under the low Tyneside bridge, their cargo transferred onto large ocean-going ships waiting in the harbor. The most frequent destination was London, the main consumer of coal from Newcastle.

Claude Lorrain, Harbor Scene with Rising Sun (Le soleil levant), 1634, etching, Gift of R. Horace Gallatin, 1949.1.22

About the Artist

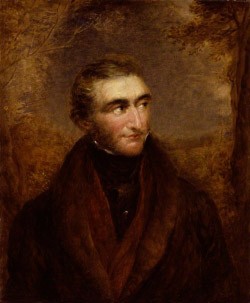

John Linnel, Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1838. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Supported by his father, a barber and wigmaker, Turner enrolled at the Royal Academy of Art at age 14. From early on, he was devoted to landscape painting and drew inspiration from earlier, 17th-century Dutch and French landscape painters while seeking to innovate a new approach and elevate the status of landscape painting. He worked extensively in watercolor, uncommon at a time when oil paint was the most esteemed medium, and handled it with virtuosic skill. Eventually, he opened his own private gallery in London, where he could experiment and exhibit groupings of his work and promote his singular vision as he pleased. His work included dramatic marine and history paintings, and often reflected his interest in capturing the sublimity—or awesome and sometimes fearsome aspects—of nature.

Turner’s high ambitions were ill-matched with his general demeanor. Considered by many uncouth in his way of speaking, unsophisticated in appearance, and inattentive to the social refinements of the day, these deficits probably prevented him from achieving his ultimate goal, to become president of the Royal Academy, a prestigious position that, much like today’s high academic posts, required social dexterity and connections.

Regardless, Turner enjoyed the admiration of his peers and ultimately, numerous art patrons. The artist was named a full Royal Academician in 1802, the youngest to be so honored. His loose and romantic style coincided with the British rejection of the highly polished, classicized French styles of painting that had dominated European tastes in the previous century. The success he so prized was his, and on his death in 1851, he was honored by the British government and people and interred in St. Paul’s Cathedral. The Turner Bequest, consisting of hundreds of paintings and drawings, is now housed at Tate Britain and the National Gallery, London.

More works by Joseph Mallord William Turner

Explore all Collection Highlights