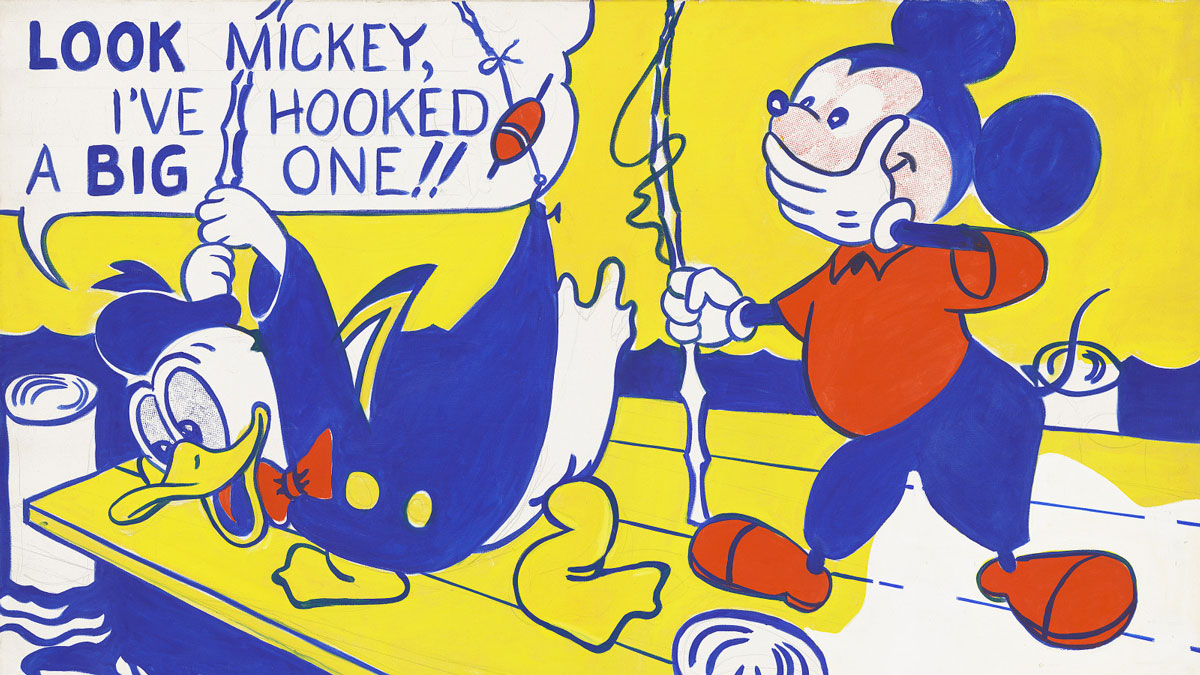

Is Lichtenstein attempting to affront fine art? Instead of painting an original image, he appropriates a scene from the Disney children’s book complete with bubble text—a visual joke. Yet he does subtly alter the original to turn it into a more unified image: omitting background figures, rotating the point of view by 90 degrees, organizing the colors into bands of yellow and blue, and simplifying the characters’ features. Stylistically, Lichtenstein imitates printed media—its heavy black outlines, primary colors, and, in Donald’s eyes and Mickey’s face, the ink dots of the Benday printing process then used to produce inexpensive comic books and magazines. In response to works such as Look Mickey, Lichtenstein was criticized for “counterfeiting” commercial images. He was even called “one of the worst artists in America” by a New York Times art critic. Lichtenstein, however, injected his art with a dark humor that inverted the visuals he transposed. By enlarging comic scenes and lifting them from their initial contexts, he presented a sly version of the clichéd image.

In Look Mickey, Lichtenstein confronts us with a scene in which the punch line comes at the expense of a popular icon—the ever-irascible Donald Duck. We come away with a feeling of ambiguity—not the simple joke we anticipated—as we identify with the narrator, Mickey, and the victim, Donald. The paradox is essential to pop art.

About the Artist

Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstroke, 1965, color screenprint on heavy, white wove paper, Gift of Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein, 1996.56.139

Andy Warhol, Green Marilyn, 1962, acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, Gift of William C. Seitz and Irma S. Seitz, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.139.1

Claes Oldenburg, Untitled (Ice Cream Cones), 1968, lithograph with embossing from a portfolio of 12 lithographs on Rives BFK wove paper, Gift of Gemini G.E.L. and the Artist, 1981.5.121.3

Roy Lichtenstein was born in New York City. In high school he began to draw and paint, taking summer classes with artist Reginald Marsh at the Art Students League. In 1940 he entered college at the school of fine arts at Ohio State University, where he was influenced by teacher and artist Hoyt Sherman. Sherman used a flash lab—a series of quickly rotating images—to teach students automatic recall to draw, stressing the connection between seeing and drawing. In 1946, after three years serving in the army, Lichtenstein returned to Ohio State to finish his degree. For 13 years he was an art professor at Ohio State, the State University of New York in Oswego, and Rutgers University. In 1963 he left Rutgers to paint full time.

Lichtenstein had his first exhibition in New York in 1951, showing work he later recalled as “in the abstract expressionist idiom” then dominating the art world. The following six years he worked in Cleveland as a draftsman and graphic designer. In 1957 he was back in New York and soon began to experiment with comic-strip characters. In 1960, Allan Kaprow, an old friend and organizer of art “happenings,” introduced Lichtenstein to other artists with similar interests, including Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. The next year Lichtenstein painted Look Mickey. It was a turning point. Lichtenstein finally rejected abstract expressionism and its emphasis on brushstroke, gesture, and the artist’s mark. He also turned from its elusive “subjects”—abstraction and expression—to clear-cut images of popular culture. Lichtenstein quickly emerged as one of the most important artists in the new pop style.

In the later 1960s and the 1970s Lichtenstein undertook an exploration of the history of Western art. His “quotations” from its signature forms (for example the classical column) and stylistic idioms (such as cubism) culminated in works that quote his own earlier paintings. Collectively they question assumptions about copy and original, reproduction and uniqueness, high and low art.

Explore all Collection Highlights