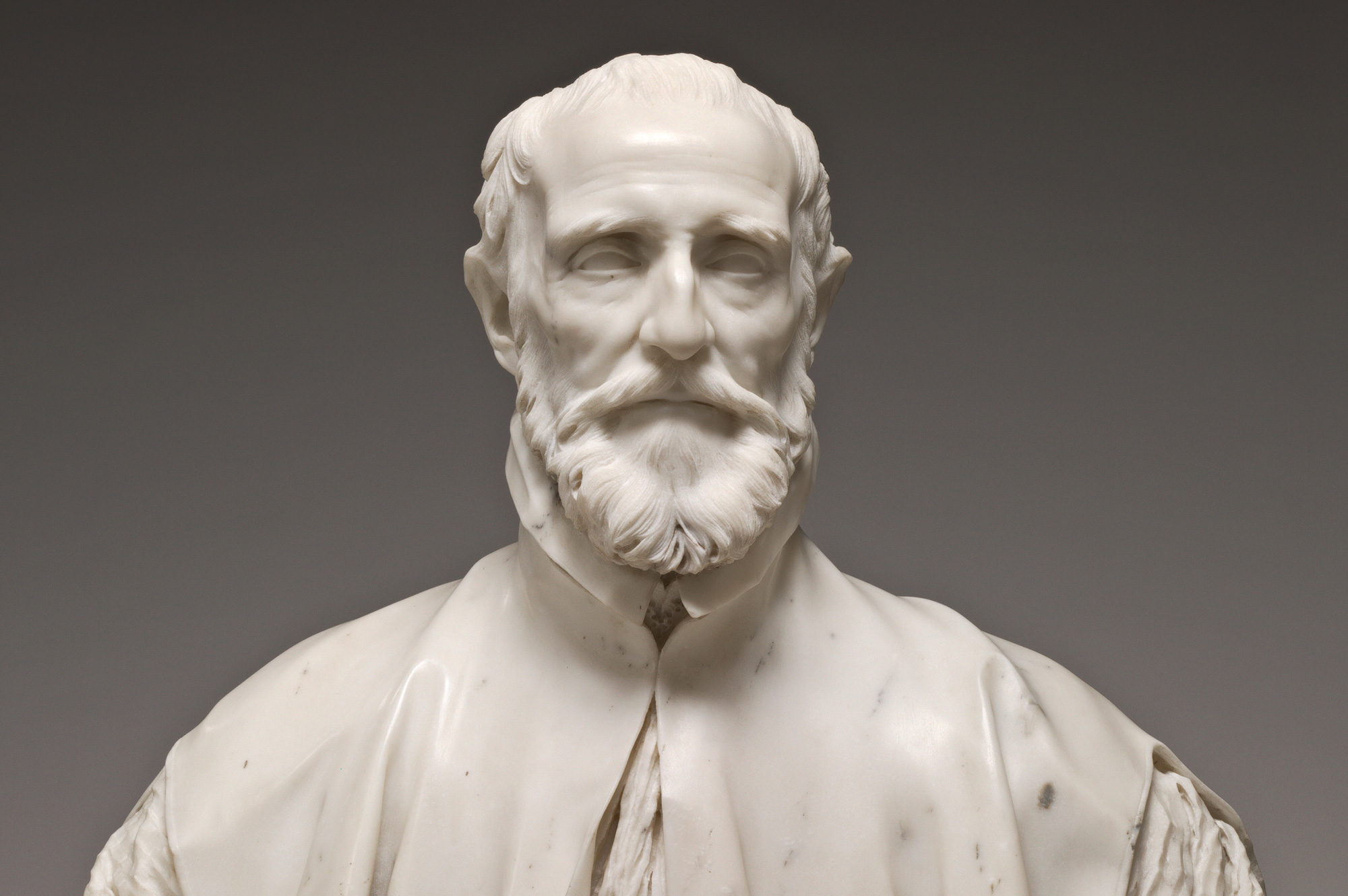

The challenges of animating a marble bust were magnified in this case by the fact that the sitter, Monsignor Francesco Barberini (1528–1600), had died more than 20 years before Bernini set to work. The monsignor was a learned man, serving in several positions within the church. He became an influential mentor to his nephew, Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII. After Maffeo’s father died when the boy was only three years old, Francesco had taken him under his care and guided his career. Before his election as pope in 1623, Maffeo commissioned Bernini to create several busts to honor family members, including this one of his revered uncle. The intricately carved bee that appears on the socle is the family’s symbol.

Bernini’s portrait busts are among the most brilliant ever made. When Bernini had a living subject before him, he preferred that the sitter talk and even walk around. It helped the artists to animate his sculptures, physically and psychologically. In the case of Francesco Barberini, the fact that his portrait was carved posthumously may explain a certain remoteness that is uncharacteristic in Bernini’s work. Bernini probably based the portrait of Francesco on a painting. Beyond the facial resemblance, details of the monsignor’s dress are identical in both the painting and the sculpture. The breadth of the chest, which is considerably larger than those that Bernini normally carved at this time, suggests the bulk of the seated figure in the painting. Bernini’s genius in carving is revealed in the intricate treatment of the shirt, deeply undercut collar, and pleated vestment with its zigzag patterns.