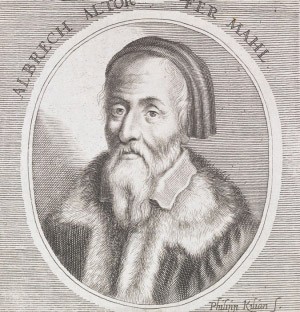

Albrecht Altdorfer, Madonna (Schöne Maria von Regensburg), c. 1519, materials, 75.8 × 65 cm, Kollegiatsstift St. Johann, Regensburg

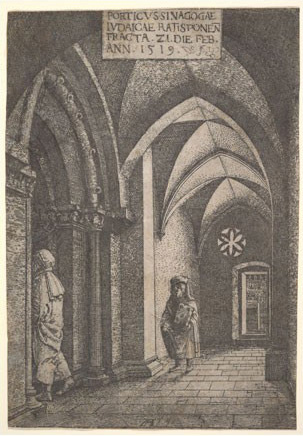

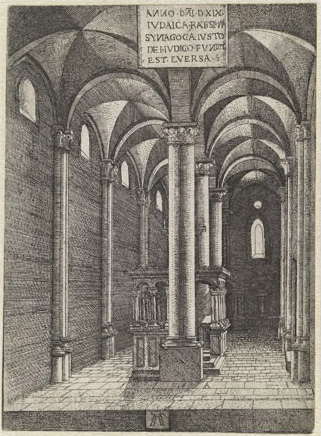

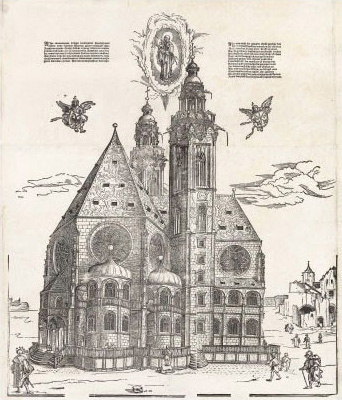

Altdorfer did not only make print copies of the Beautiful Virgin. Earlier, he had made this reproduction in paint. Both the original icon and his painted copy remain in Regensburg today. The icon was believed to have been painted from life by Saint Luke, but was surely a product of the 13th century. It is one of hundreds of venerable images that were associated with the saint and ascribed miraculous powers. Before the events of 1519, however, the Regensburg Virgin had apparently not received much attention. It was elevated from obscurity only by the fervor generated by the new miracles—and the anti-Jewish violence. The inscription on the Beautiful Virgin print, repeated three times, emphasizes her purity: “You are of perfect beauty my love, and there is no blemish on you. Ave Maria.” Pilgrims would have understood a subtext immediately, recognizing the contrast implied between the stainless Virgin and the “diabolical influence” of the synagogue her shrine replaced. After the early 1500s, the Beautiful Virgin returned to obscurity. The 13th-century icon was only rediscovered, hidden under layers of overpaint, in the 1930s.

For those who came to venerate the Beautiful Virgin and ask her help, all the images of her—the original icon, Altdorfer’s painted copy, the prints, the tokens—were imbued with the same spiritual power. Prints were not simply mementos of pilgrimage but also devotional objects in their own right. They made the miracle-working image accessible to a wider population and, of course, were portable. A portrait by Petrus Christus illustrates a similar print as it would have been used at home. The fact that these prints were tacked to walls and handled by men and women while making their devotions made their survival fairly rare in spite of the thousands that must have been produced. Several examples of this Beautiful Virgin print are known, many printed with fewer tone blocks and some with the black line block only.

Jacob Kern, a stonemason, was grievously injured in the melee, either from a fall or by a collapsing beam. He was given no chance for survival, but his wife prayed fervently to the Beautiful Virgin, and Jacob recovered. Known in German as the Schöne Maria, this was a venerated painting of the Virgin and Child from the 13th century. Jacob had believed himself in no danger, because, he said, the Virgin had held his hand during the entire ordeal. News spread quickly about the miracle-working image. Soon there were 54 miracles reported, then 74. The pope granted an indulgence of 100 days for devotions made in front of the Beautiful Virgin, and pilgrims arrived in droves. “All sorts of people came,” one witness noted: “some with musical instruments, some with pitchforks and rakes; women came with their milk cans, spindles and cooking pots. Artisans came with their tools: a weaver with his shuttle, a carpenter with his square, a cooper with his measuring tape. They walked many miles, but did not tire from the long journey. They all walked in silence. If asked why there were going, they answered: My spirit drives me there."