Not far from the National Gallery, the walkways of the Tidal Basin flood daily. A reservoir completed in 1887, the basin was designed to regulate the tides of the Potomac River. But due to increasingly paved surfaces limiting the ground’s ability to absorb rain, the gradual sinking of the land (subsidence), and climate change, the river’s water level is rising. The basin can no longer perform as intended. Floods force people to find alternative walking routes as water slowly claims back its predominance over the land.

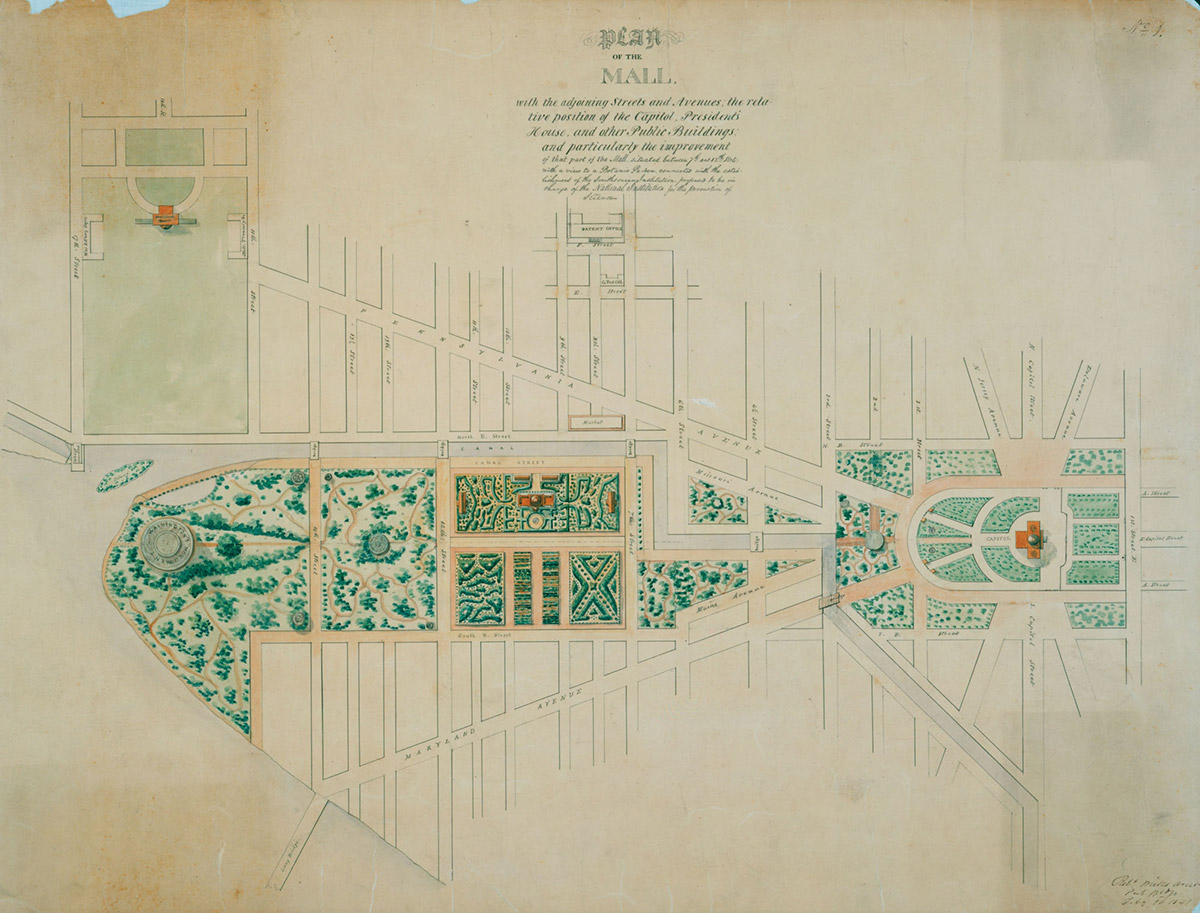

The National Mall—today a broad, tree-lined green that extends from the foot of Capitol Hill to the Washington Monument—has been redesigned and reimagined many times, always contending with the waters of the Potomac River. The History of Early American Landscape Design, a digital project by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, makes available historic plans for the National Mall from between 1791 and 1852. They show how much planning went into taming nature—water in particular. At various times, visionary designs called for waterfalls, a lagoon, a canal (that was indeed built, and ultimately filled in, during the late 19th century), and planting indigenous trees. The most prominent architects of their time shaped the National Mall, and their plans are becoming relevant again today as we seek new solutions to respond to the challenges of rising waters.

One of the first plans, laid out by military engineer Pierre-Charles L’Enfant in 1791, included a waterfall at Capitol Hill (then Jenkins Hill). Its waters were to merge into a canal running next to the mall, a few feet away from the current site of the National Gallery. The plan comprised a grand avenue along the mall and adjunct fields near the banks of the Potomac River.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Plan of the Washington Canal, No. 1,” February 5, 1804, in John W. Reps, Monumental Washington, The Planning and Development of the Capital Center (1967), fig. 17. Original plan at Library of Congress, Washington, DC

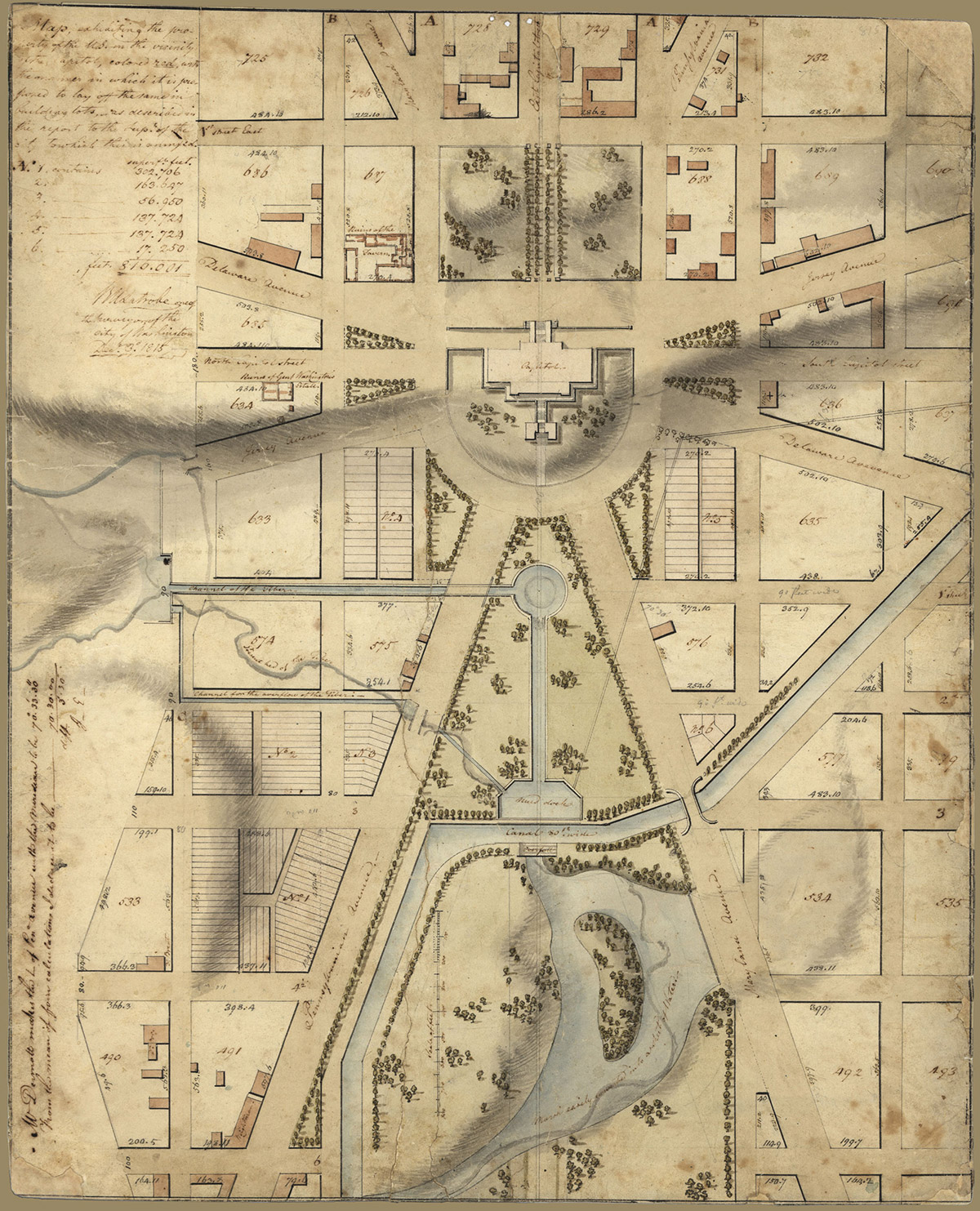

The area, which originally featured rolling hills, was developed throughout the 19th century. In 1815, Supervising Architect of the United States Capitol Benjamin Henry Latrobe delivered a plan that also included a waterfall—as well as a lagoon that was to occupy a considerable amount of land between bridges over Pennsylvania and Maryland avenues. A small canal would run from a basin at the foot of the Capitol into a larger canal, eventually releasing the water into the Potomac.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the Capitol grounds, 1815, watercolor on paper, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

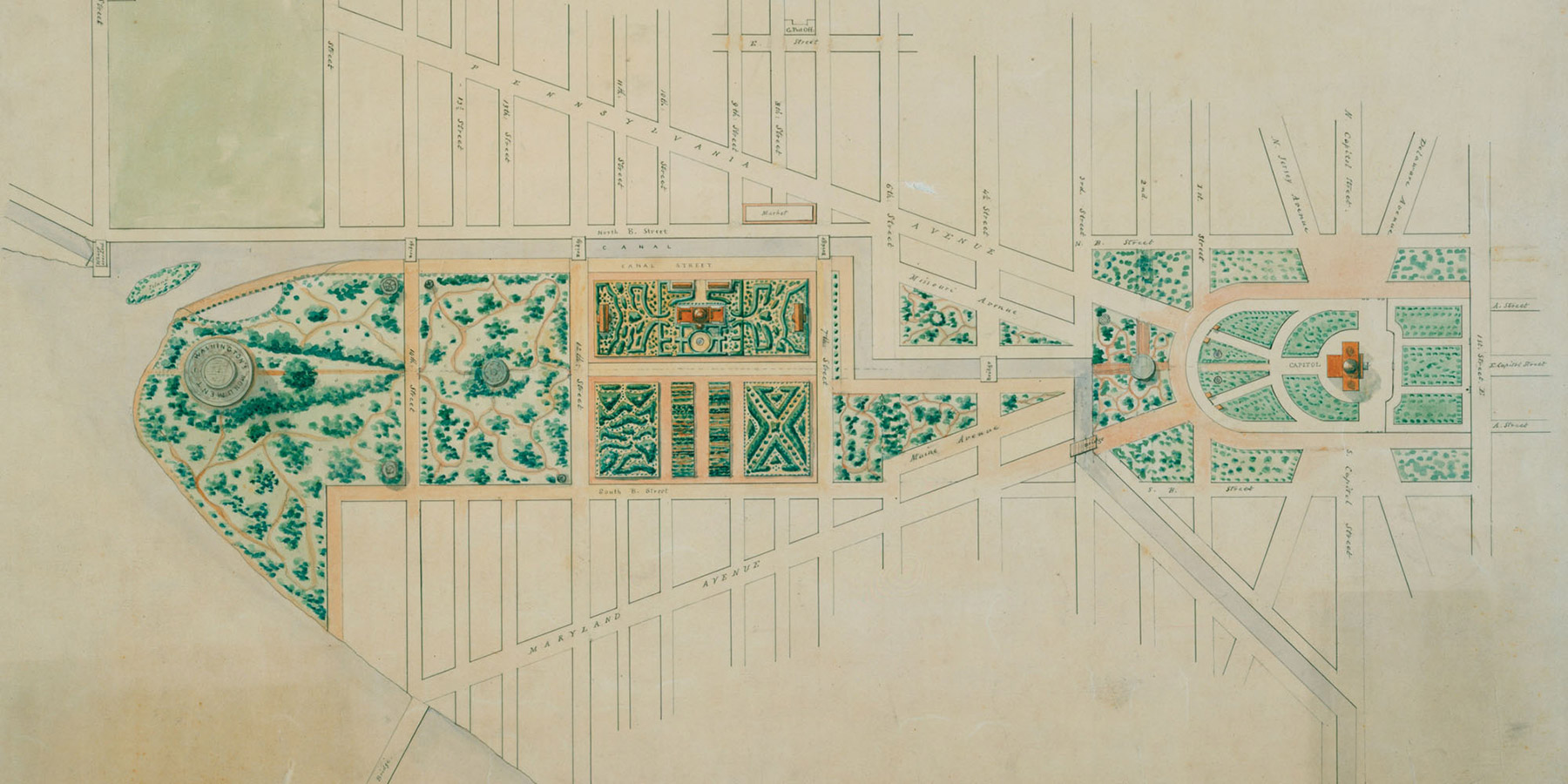

In 1841, Robert Mills delivered a comprehensive plan of the National Mall as part of a project for the gardens of the Smithsonian Institution. Although Mills’s plan had limited impact at the time, his naturalistic vision of the mall as a site for scientific investigation and display set the tone for future designs. A decade later, architect and horticulturalist Andrew Jackson Downing worked to implement the grounds of the mall as a national park; his plan would remain significant for years to come. In the mid-19th century, Mills’s and Downing’s plans informed the planting of 2,000 indigenous trees, an attempt to display the richness of the natural world.

Robert Mills, Plan of the Mall, Washington, DC, 1841. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland

As buildings and monuments are added, the mall continues to adapt to new demands—but many of these historical plans have had a long-lasting impact. L’Enfant’s early design, for instance, proved influential for the mall’s current shape, which was cleared following the McMillan Plan of 1902 (named after Senator James McMillan, chair of the plan commission).

One of the designs submitted to the Tidal Basin Ideas Lab. Image courtesy of GGN.

Today, in the face of a mounting ecological crisis, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Trust for the National Mall, and the National Park Service, created the Tidal Basin Ideas Lab. Proposed through this initiative, plans to address the crumbling sea wall suggest potentially replanting the renowned cherry trees, building bridges or platforms for elevated points of observation, and redesigning the water's edge. As they did throughout the 19th century, architects are now considering both initiatives to control the water and visionary plans that embrace rather than reject it. In the future, marshes may replace the Tidal Basin—perhaps even a lagoon, as Latrobe originally envisioned, will become a new feature of the National Mall.