Edgar Degas’s experimentation is unsurpassed in 19th-century French art, whether he was making pastels, drawings, prints, sculptures, or paintings.

The enigmatic Two Women encapsulates his instinct for exploring the range of capabilities in whatever materials he chose to use.

The work’s curious composition catches the eye: are these two identically dressed women, or the same woman seen at different moments? Why are they performing in someone’s home and lit from below, as if on a stage?

Degas left such questions unanswered while he reveled in rendering different kinds of marks using opaque pastel and more transparent watercolor. His inventive combination of the two mediums to depict various textures and set off the figures from the background was unusual for the period.

Edgar Degas, Two Women, c. 1878/1880, pastel over watercolor and charcoal on tan laid paper, mounted to board, Corcoran Collection (William A. Clark Collection), 2014.136.176

For Two Women Degas chose a pinkish-tan paper with red, blue, and dark-brown fibers dispersed among those of light tan. Unlike other works in which he covered most of the surface with pastel, such as Young Woman Dressing Herself, in Two Women the artist allowed the paper to show through. This provided a unifying background color to the scene and highlighted the individual marks.

Detail from above the left knee of the woman on the right; a charcoal line, outlined in blue, lies to the left of two black pastel marks.

Taking a stick of charcoal, Degas first lightly sketched a few outlines of the most important elements of the composition. Hints of the charcoal lines peek out from below the denser marks of pastel, although they can only be distinguished from black pastel by using a microscope.

Detail of the face of the woman on the left

In the woman on the left, Degas sensitively sketched the eyes, nose, and mouth with brownish-purple pastel and then added bold marks of more brightly colored pastels to her face and neck. He created the shading in the eyes by rubbing the pastel with the pointed end of a tool called a stump, a rolled piece of leather or paper. These diffuse marks contrast with the deliberate, densely pigmented strokes of yellow, blue, pink, black, and white in her face and neck.

The tightly spaced vertical lines in the yellow relate to the paper’s texture. If a pastel stick is lightly moved across the paper, the pastel particles tend to cluster on the ridges of the paper surface and merely drift into the valleys.

Compare these yellow marks to the deep blue collar, where Degas applied more pressure on the pastel stick, and to her shoulder, where he blended the central area of pink with his fingertip. In both cases, the paper is more evenly covered, and the marks do not appear broken as in the yellow.

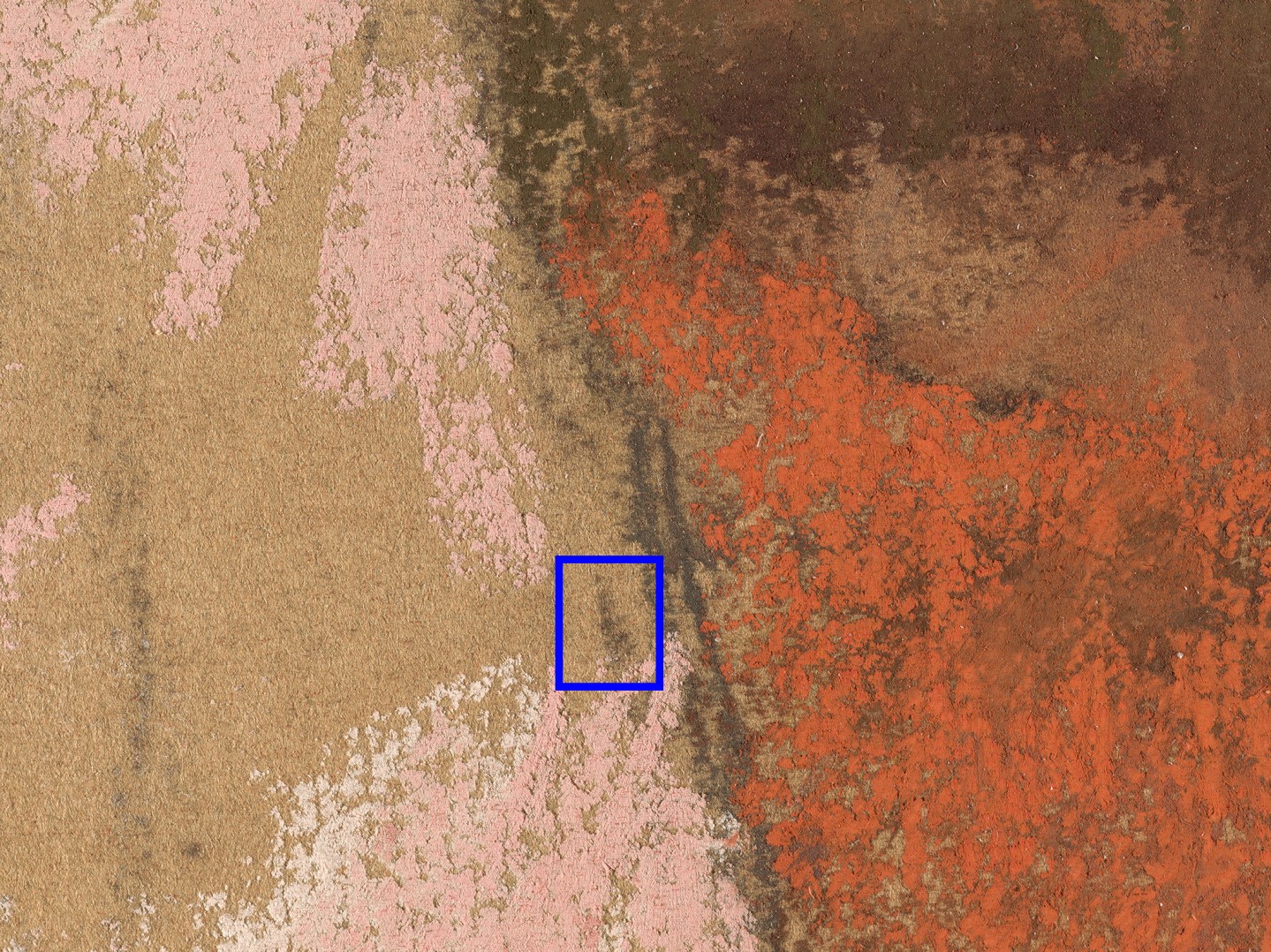

Detail of the patterned wall covering behind the figures

To create the textured wall covering, Degas combined rough marks of powdery pastel with flowing lines of watercolor, juxtaposing contrasting yet harmonious colors. He first laid in vertical brushstrokes of purple-red watercolor and washes of light brown. Then he overlaid the strokes of watercolor with dappled, horizontal marks of pastel in blue-green and red-orange. By applying denser, less open marks of pastel in the figures, he made the intricately colored background recede in space.

Bodice of the woman on the right, showing crushed pastel mixed with water and applied by brush. This photograph was taken in raking light (light from a slanted angle), which helps reveal texture.

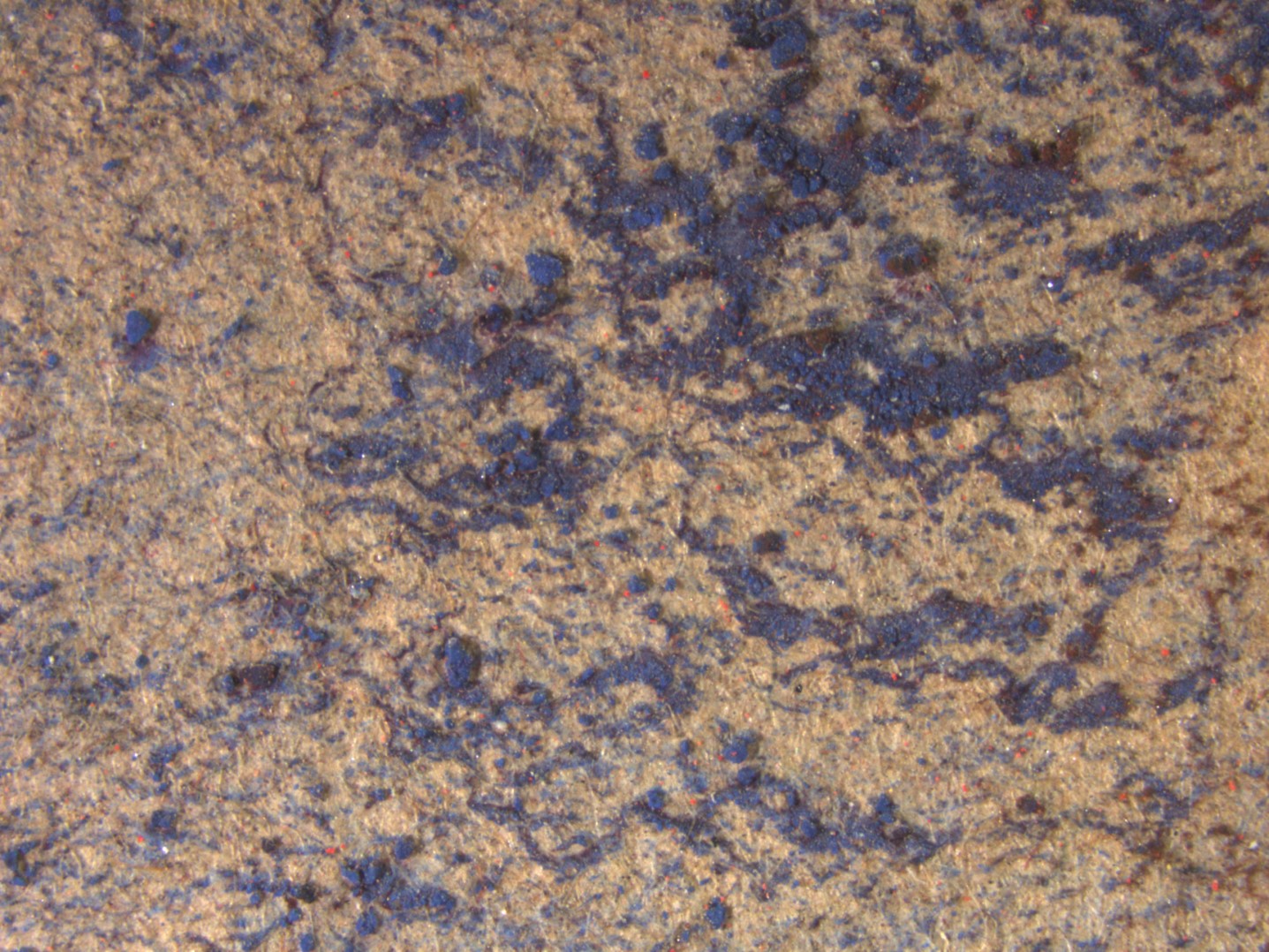

Magnified detail of the crushed pastel

Degas often experimented with applying the same material in different ways. In several works, he crushed pastel sticks and mixed the crumbled pigment with water, sometimes adding gum arabic, to make a thick matte paint that he applied with a brush.

To color the bodices of the women’s dresses in this drawing, he instead may have hastily thrown bits of pastel into liquid and puddled the mixture on the paper. As it dried, the watery paint deposited lacy trails of clumped pigment that resemble a patterned silk and bear witness to another example of Degas’s creative explorations.