While the nation and much of the world watched live video of NASA’s Perseverance rover touching down within the Jezero Crater on Mars on February 18, a handful of National Gallery scientists and conservators felt a special sense of pride. The same science that NASA uses to analyze the geology of our nearest planetary neighbor is being applied in the National Gallery’s scientific research department to explore the properties of works of art.

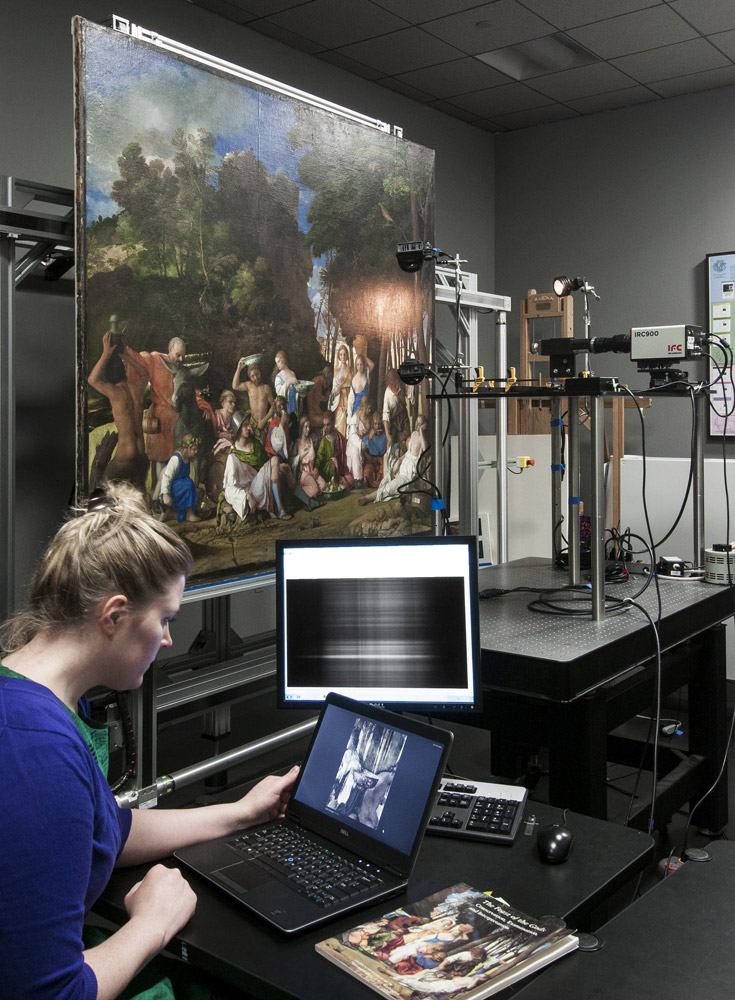

Senior imaging scientist John Delaney and senior paper conservator Michelle Facini set up data collection using visible reflectance imaging spectroscopy in the chemical imaging lab at the National Gallery.

Reflectance imaging spectroscopy is the term for this technology, explains John Delaney, senior imaging scientist at the National Gallery. He and his colleague, imaging scientist Kate Dooley, lead the high-tech exploration of work by artists such as Lorenzo Monaco, Giovanni Bellini, Johannes Vermeer, Pablo Picasso, and Jackson Pollock. Their analysis can unlock the secrets of an artist’s technique and materials. Reflectance spectroscopy measures the amount of light reflected from a material at different wavelengths, that is, its “spectral signature.” Measuring spectral signatures can help identify materials—the specific pigments, for example, in a centuries-old illuminated manuscript.

As Delaney explains, “NASA has a camera system orbiting Mars called CRISM”—Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars. “CRISM analyzes spectral signatures over the surface of Mars to look for minerals that formed in aqueous conditions. These minerals could indicate the presence of former biological activity on Mars. We developed our own CRISM—a hyperspectral reflectance camera—that allows us to collect reflectance images and spectral signatures from across the surfaces of paintings.”

“From this imaging data,” adds Dooley, “we can make maps of specific pigments derived from minerals. The distribution of minerals in a painting, in addition to the paint binders, provides insight into an artist’s working methods. We can also make images that may reveal preparatory sketches or revisions that are hidden below the surface.” One such hidden painted sketch, unrelated to the final composition, is the image of a woman wearing a white mantilla with a gold cross necklace, discovered beneath Pablo Picasso’s Blue Period painting

Imaging scientist Kate Dooley collects data using infrared reflectance imaging spectroscopy on The Feast of the Gods (1514/1529) by Giovanni Bellini and Titian.

Imaging lab analysis showed how Jackson Pollock used both slow-drying oil paints and faster-drying alkyd paints in his iconic “drip” paintings. The National Gallery’s reflectance imaging system can also map the brilliant colors in illuminated manuscripts, often derived from minerals—from blue-green azurite (copper carbonate hydroxide) to deep red iron earth pigments such as hematite. “Hematite is also found on Mars,” notes Delaney, “a key early indicator for minerals that most likely formed in the presence of water.”

Reflectance imaging spectroscopy is an emerging field at museums. “There are very few places that have the benefit of this equipment,” Delaney notes. “Our colleagues at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam have adopted camera systems and equipment similar to what we designed. The National Gallery, London, cloned our hyperspectral systems, and the Getty Museum is about to establish the same capability.”

This is not to say that such technology has replaced the practiced eye of a curator or the careful microscopic study by a conservator when it comes to analyzing art. Rather, spectral analysis is one tool in a collective approach.

“Kate and I first go through our data, then we sit down with the conservators and compare it with their data, then we meet with the curators. It’s a very collaborative process,” says Delaney. “It takes a team to do this work. And it’s more fun that way.”

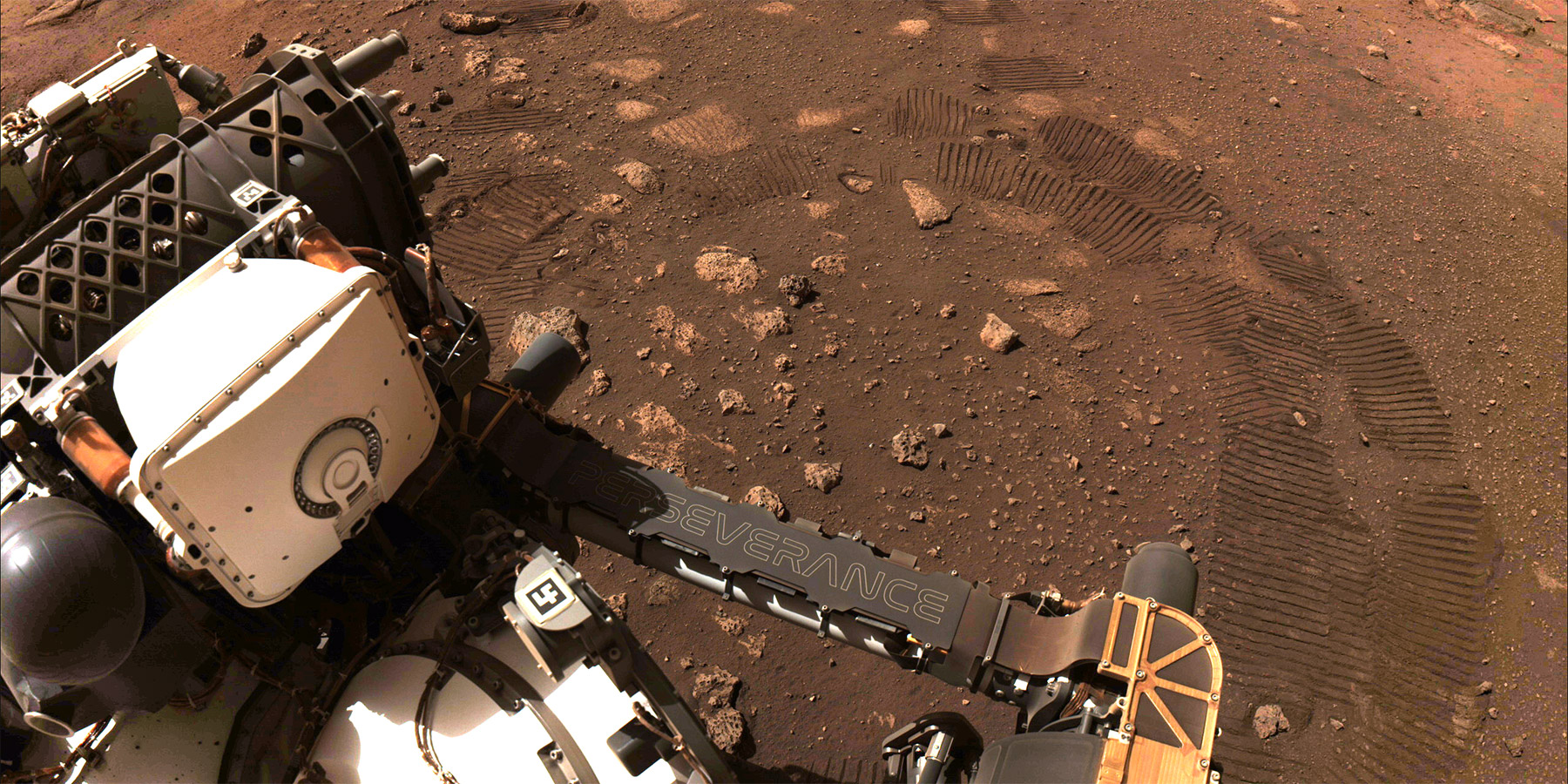

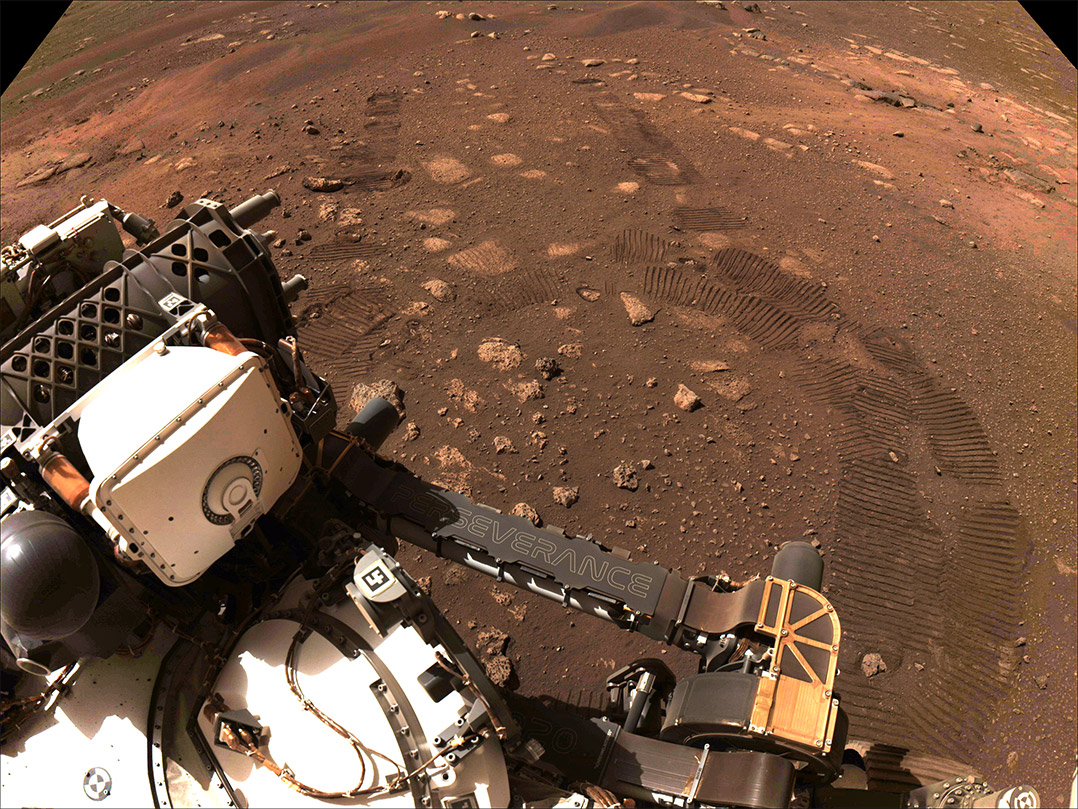

NASA’s Perseverance rover takes its first drive on Mars, March 4, 2021. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

And more convenient. To gather data from the surface of Mars, NASA has to launch a rover 300 million miles into space. “But here at the National Gallery,” Delaney smiles, “we just need the artwork brought into the imaging lab.”

Banner: NASA’s Perseverance rover takes its first drive on Mars, March 4, 2021. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech