When David Driskell arrived in Washington, DC, in 1949, he was just 18 and eager to enroll as a student at Howard University. When told that he would need to apply for admission and that classes had begun three weeks earlier, he simply refused to leave. Thirteen years later he would be invited to join the faculty. His mentors James L. Wells and James A. Porter had helped establish the preeminent program in African American art at Howard. Over time, David would play a critical role in carrying that legacy forward.

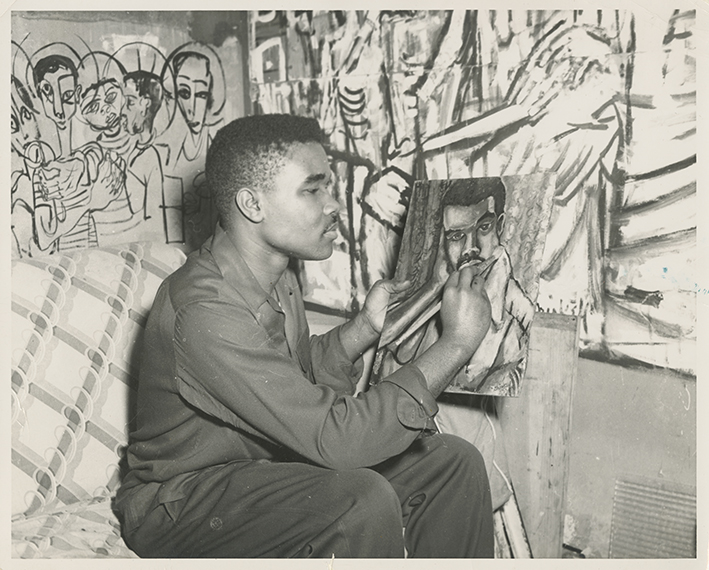

David Driskell working on a self-portrait in his studio, Washington, DC, 1953. Courtesy of the David C. Driskell Papers at the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park. Gift of Prof. and Mrs. David C. Driskell (MS01.11.01.P0013)

A gifted artist as well as an inspiring teacher, David recalled his early years in Washington during a 2007 interview at the National Gallery of Art. The nation’s capital was a strictly segregated city when David arrived, and he quickly learned that there were only three restaurants where he, or any other African American, could eat. One was the cafeteria at the Gallery. With a laugh and a smile, David confessed that initially he came to the Gallery not for the art, but rather for the food. As a student and then as a teacher, he frequently returned to the museum and to the galleries he would later describe as adjunct classrooms.

I did not meet David until 2007, when he participated in a public program focused broadly on African American art and more specifically on his own work. Several years later, when the opportunity to acquire a significant painting by a key Harlem Renaissance figure suddenly became a possibility, I called David to ask for his advice.

As curator of American art at the Gallery, I had been searching—without success—for a major work by Aaron Douglas to add to the collection. In the fall of 2014, a longtime friend called with word that two remarkable paintings by Douglas might be available. When I contacted David, the works had just arrived at the museum. I asked if he might have time to come see the paintings and speak with us about their importance. Ever gracious, David agreed to come. It was during that afternoon conversation in front of those two paintings that I learned of David’s deep affection for the Gallery and his gratitude for the welcome he had received as a teenager in 1949.

The paintings David came to see were titled Let My People Go and The Judgment Day—large-scale versions of illustrations Douglas had created during the 1920s to accompany James Weldon Johnson’s celebrated publication God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. David had included both works in his 1976 landmark exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art, and because he had replaced Aaron Douglas as head of the art department at Fisk University upon his retirement, David was literally a living link to the artist.

Before David arrived, my colleague Charles Brock and I moved the two paintings to a semiprivate viewing area and borrowed several comfortable chairs, hoping to encourage a relaxed conversation. Little did we know that David would spend several hours with us sharing recollections of Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, and a host of other friends from years past. Prompted, perhaps, by works he knew well but had not seen since the 1970s, David reminisced about Fisk University and seeing the paintings then before us in Aaron Douglas’s home. From time to time David became quiet, seemingly lost in memories. Late in the afternoon he spoke of his father, an Appalachian preacher whose sermons embraced the call-and-response tradition of the black church that Douglas had captured in his illustrations for God’s Trombones. Black preachers were God’s trombones.

Shortly after David’s visit the Gallery acquired The Judgment Day, the final work in the God’s Trombones series and the first painting by Aaron Douglas to enter the nation’s collection. Later, when the painting had been hung in the American galleries, David returned to the museum. We went together to the gallery where the painting was on view. He seemed pleased. He had recognized the importance of the work decades before others—patience rewarded and acknowledged with a modest smile.