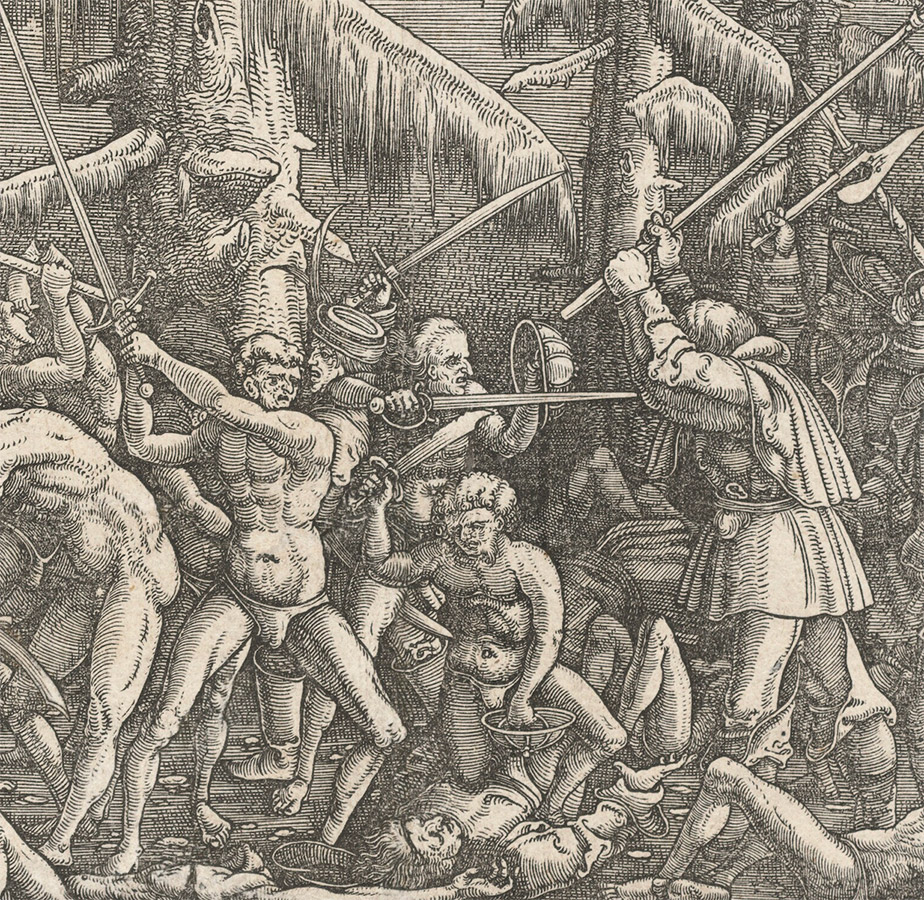

Hans Lützelburger’s Battle of Naked Men and Peasants shows a bizarre stand-off between semi-nude men and German peasants. They strike each other with swords, clubs, and farming tools such as flails and scythes. The men twist in a variety of poses that remind us of carved Roman friezes and earlier Italian engravings. The complex tangle of bodies both recalls and challenges these examples. This battle, however, is set within a northern forest of drooping fir trees and is cut from a humble block of wood. The mysterious subject is not based on any known literary source.

Hans Lützelburger, after Master NH, Battle of Naked Men and Peasants, 1522, woodcut on laid paper, Ruth and Jacob Kainen Memorial Acquisition Fund, 2017.21.1

As a result of the print’s unclear meaning, we spend extra time searching for clues in the composition—in the angry faces of the fighters and the moody landscape. Are we seeing a conflict between past and present or a contest between primitive warriors and their contemporary counterparts? Who is winning the war and what are the stakes? And who are the two half-naked men at the lower left holding drinking vessels? Some scholars have suggested that they might be comical portraits of printmaker and designer, but the print doesn’t give us any easy answers.

Lützelburger’s Printmaking Career

The sheet is a tour-de-force sampler of Lützelburger’s technical skill and versatility as a block cutter. All at once, he demonstrated his ability to carve heroic figures, dramatic landscapes, and even the practical type that printers needed for their presses. At the same time, he created an entertaining and awe-inspiring work that would have appealed to an emerging class of print collectors looking for novelty.

Lützelburger’s intricate woodcut is full of details that express the tension of combat in an eerie woodland setting.

When he was making this print in 1522, Lützelburger was at a professional crossroads. For several years he had been employed in the large printmaking workshops in the city of Augsburg that served the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. Working as a Formschneider, or block cutter, Lützelburger skillfully translated other artists’ designs into printed multiples. With gouges and chisels, he carved woodblock surfaces so that only the lines of the composition remained in relief. They would be coated with ink and printed repeatedly on sheets of paper using a press.

Lützelburger had labored on Maximilian’s largescale memorial woodcut projects along with dozens of other talented—and typically anonymous—craftsmen. But the emperor’s death in 1519 stopped work on these publications, and the local print industry began to dry up without its patron. To continue making a living as a block cutter, Lützelburger had to leave Augsburg in search of new print publishers and artists to work with.

16th-Century Printmaking as Self-Promotion

Fortunately, Lützelburger understood that prints were not only profitable but also powerful self-promotional tools. In the early 16th century, printing large quantities of images on paper was relatively cheap. The prints could then travel in many directions at once, offering a direct path to new audiences at home and abroad. They served as agents, carrying a printmaker’s style and name to foreign lands.

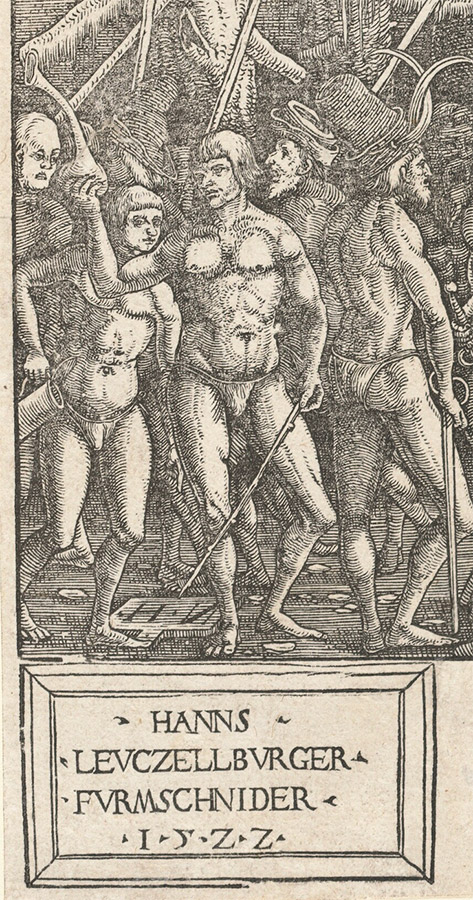

Are these figures meant to be comical portraits of the printmakers behind the woodcut? The tablets at their feet name Hans Lützelburger as the print’s craftsman but leave us guessing about the identity of NH, the woodcut’s now anonymous designer.

Lützelburger appears to have been the driving force behind this version of Battle of Naked Men and Peasants. We don’t know the name of the artist who designed the print. He is identified only by the initials NH in a corner of the image. Lützelburger, on the other hand, added a woodblock that includes his entire name; confidently proclaims his role as “FVRMSCHNIDER”; and notes the date, 1522.

Lützelburger’s bold self-promotional strategy seems to have worked. Within a year, he had moved to Basel, another of northern Europe’s great printmaking hubs, and begun working with some of the period’s greatest artists and publishers.

The daring Battle of Naked Men and Peasants, however, is a testament both to Lützelburger’s ambition and to the power of print to affirm and preserve artistic identity. Published, in part, to advertise his eagerness to work with his contemporaries, it has also preserved his name for future generations. Five hundred years after it was made, this rare sheet survives as a record of the craftsman’s talent and enterprise.