What Is Impressionism? 4 Things to Know

Impressionism is one of the most recognizable art movements in the world today, but it was revolutionary in its time. Originating in France in 1874, it was rejected by critics at first—only later embraced as a national symbol.

In the mid-19th century, France saw rapid technological and social changes. Gathering in cafés to discuss these societal transformations, the impressionists found opportunities for liberation. They changed the way they painted, in both subject matter and technique. They also met to discuss how, when, and where to exhibit their art. Learn more about the movement and discover the telltale markers of an impressionist work of art.

1. The term “impressionist” came from a derisive review of a Claude Monet painting.

In 1874, Monet’s Impression, Sunrise appeared in the first exhibition held by an association of artists. They called themselves La Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs, etc. (the Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, etc).

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas, Musée Marmottan Monet, gift of Eugène and Victorine Donop de Monchy, 1940. Inv. 4014. Photo: © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Studio Christian Baraja SLB

Journalist and art critic Louis Leroy published a scathing review titled The Exhibition of the Impressionists. In Leroy’s article, two imagined skeptical viewers scratch their heads at the works on view. One of them comments on Monet’s painting: “Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

Leroy used the term “impressionist” disparagingly. But it became a rallying cry for artists like Berthe Morisot, Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and others.

2. Impressionists used thick, loose brushstrokes of contrasting color.

When the impressionists first began exhibiting, the Académie des Beaux-Arts was still the arbiter of taste. It exercised its influence through Paris’s annual exhibition, the Salon. The academicians favored precise drawing, carefully rendered composition, and smoothly finished surfaces.

But impressionist painters broke with that tradition. They did not conceal their brushstrokes. They used choppy marks and dabs of unblended colors. They did not hide the fact that their works were made of paint. They were not seeking an illusion of reality.

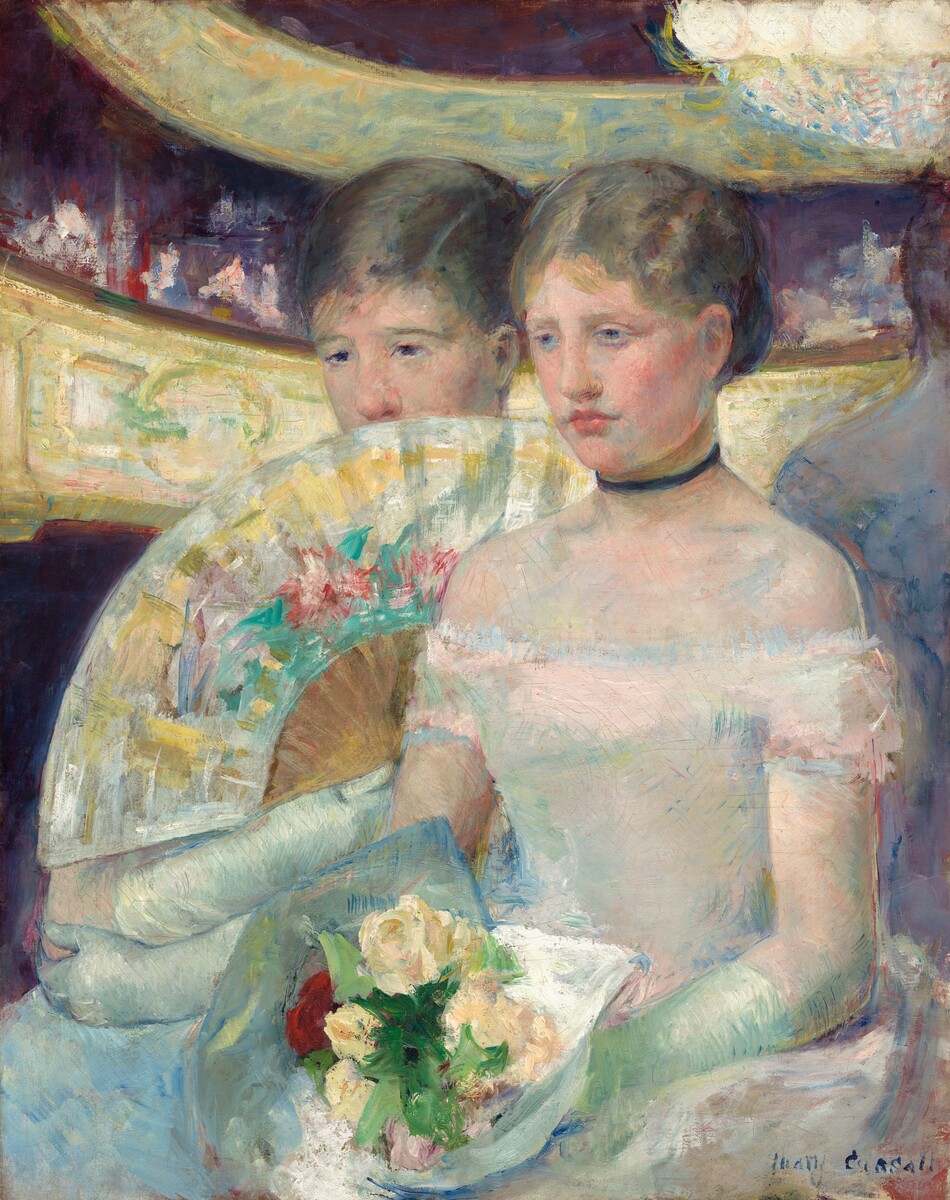

Compare Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ portrait of Madame Moitessier, with Mary Cassatt’s The Loge.

Ingres was the quintessential academic master. He rendered Madame Moitessier’s black lace and shiny baubles in exquisite detail. Cassatt merely suggests the satin of her opera-goers' dresses through luminous color, and not delicate threadwork and draping.

Madame Moitessier's complexion and hair are smooth and shiny in Ingre's portrait. Meanwhile, the faces of Cassatt’s subjects are crisscrossed with blue, yellow, purple, and red hatch marks. One of them even conceals her face with a fan, an anonymity no wealthy patron would tolerate.

3. Impressionists worked outside in nature, paying close attention to light and color.

The impressionists took their canvases and easels outdoors, an en plein air working style made possible by recent innovations. Paint tubes had made oil paint portable, and the rail system allowed quick excursions from Paris to the countryside.

Of course, artists had already been making careful observations of nature outdoors. But they had been recording them in sketches and studies to be referenced later in their studios. This had allowed them to combine different components and compose idealized scenes.

By working on full paintings outdoors, impressionists quickly captured the initial sensations that landscapes elicited. There was no time to carefully model objects and structures. The artists also had to adapt to changing light and weather conditions.

Monet advised young painters:

“When you go out to paint, try to forget the objects before you, a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here is a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naive impression of the scene before you."

4. Impressionists placed modern life at the center of their art.

The Académie had followed a strict hierarchy of subject matter. At the highest level, art was to depict a moral narrative: from history, the Bible, or mythological stories.

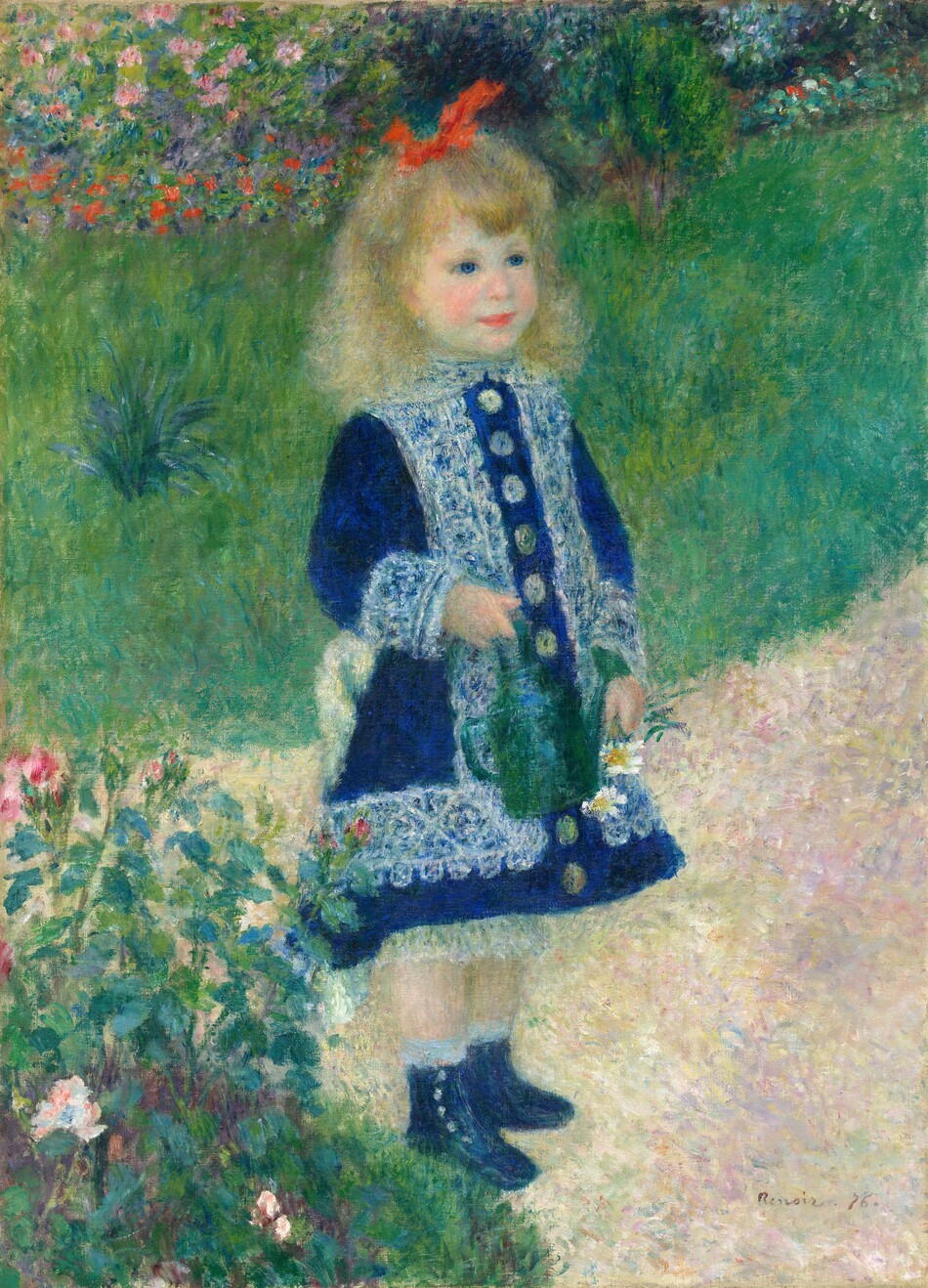

But the impressionists turned away from these themes. Instead, they sought to capture their current moment, a time of enormous upheaval. Paris was just emerging from the Franco-Prussian War and a brief but brutal civil war. The city was reborn into a modern metropolis. It played backdrop to middle-class leisure activities like boating and horse races, the ballet and the opera. Its new railways became gateways to the enjoyment of nature in the countryside.

The impressionists’ sitters are painted not in glamorous poses, but in the moments in between. They’re at rest or lost in thought. They are shown in newly available ready-to-wear clothing instead of luxurious fashions. They are not wealthy patrons, but friends, relatives, or laborers. To viewers accustomed to grand paintings of important people and dramatic events, these works felt thoroughly modern.

More than a century later, the paintings still strike us as breezy and refreshing. Impressionism forever changed the trajectory of Western art—and the way we look at pictures.

You may also like

Article: 1874: The Birth of Impressionism

Discover how a landmark exhibition led to the birth of an influential movement.

Article: Edgar Degas Only Made One “Little Dancer.” And It’s Ours.

How our conservators have cared for the fragile wax sculpture, preserving it decades longer than anyone thought possible.