Emmi Whitehorse Paints the Harmonies of Her Homelands

“My work has always been about the land,” says Navajo (Diné) painter, Emmi Whitehorse. She was born in Crownpoint, New Mexico, just east of Mount Taylor. The landscapes of her ancestral homelands have given her a unique and intimate art-language with which to tell her stories. “Light, space, and color are the central axes around which my work has evolved.”

Whitehorse’s birthplace, her family, and the work of other Indigenous artists all inform her abstract paintings. Seasonal changes, organic forms, and the silence of solitude contribute to the serene, dreamlike atmospheres of her canvases.

Emmi Whitehorse, Fire Weed, 1998, chalk, graphite, pastel, and oil on paper mounted on canvas, 38 1/2 x 50 inches, Brooklyn Museum, Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Early Education in Color Composition

“As a child, I was pretty solitary,” says Whitehorse. “I was the baby of the family, and I was too young to do what my siblings were doing, so I spent a lot of time alone.”

Much of her childhood was spent helping her grandmother tend to the family’s herd of sheep and goats. She kept a close eye on them while they grazed the high-desert flora. And she helped in the seasonal harvesting of wool, some of which was sold to textile mills for commercial processing.

The rest, her grandmother transformed into weavable yarn through an alchemic, centuries-old Diné tradition. She then hand loomed it into colorful blankets and rugs.

Grandmother’s woven masterpieces provided an early education in color and composition for the young Whitehorse. They were dyed with pigments extracted from native plants and vegetation from the surrounding hillsides. The family matriarch also instilled in her granddaughter the Navajo philosophy of Hózhó: “a harmonious balance between nature, humanity, and the whole universe.”

“My grandmother never went to her loom when she was upset,” Whitehorse recalls. “And I never approach a canvas when I’m angry or in a bad mood. Those feelings and emotions can get transferred into the work and throw things off balance.”

A Modern Indigenous Creative Identity

Whitehorse, now in her sixth decade, has been painting since she was in high school. It was a first-place award in an art contest that set her on the path to becoming an artist. “I bought a set of paints with the prize money,” she recalls, her excitement still palpable.

In the late 1970s, while studying at the University of New Mexico, Whitehorse joined the Grey Canyon group of artists. Its members included founder Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith and Conrad House. The group “defied expectations placed on Indigenous-made art by utilizing modernist abstraction to express Indigenous themes or worldviews.” It nourished Whitehorse’s creative identity, strengthened her artistry, and started the foundation for her life’s work.

Whitehorse also drew creative influence from artists like abstract expressionist Cy Twombly and Latvian American modernist Mark Rothko. Both artists used color as hue and form, applying their respective favored palettes to create structure, shape, and contour. And both relied heavily on a sense of order created by this dynamic.

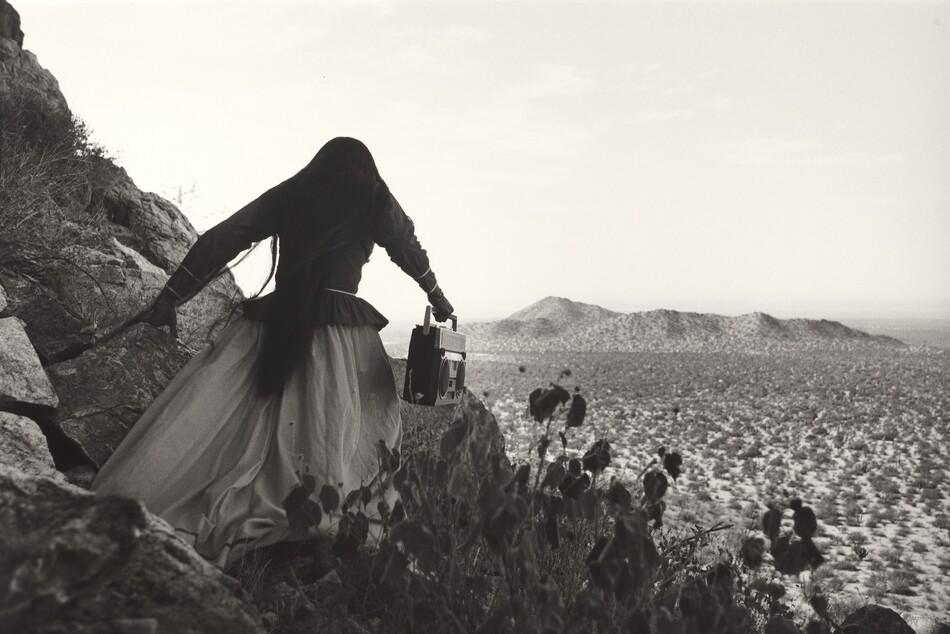

Emmi Whitehorse stands outside her studio in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Whitehorse’s career has now spanned more than four decades. Her work has appeared in numerous national and international exhibitions, including The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans at the National Gallery.

Today, Whitehorse creates in her south-Santa Fe studio. She paints against a soundtrack of the natural world: wind, a bird fluttering into flight, thunder announcing a coming storm, rain against the hard, dry earth. Far away mountains, sage-covered mesas, and wind-sculpted buttes against an endless, ever-changing horizon offer even more inspiration.

Symbols Celebrating Nature’s Design

Her paintings “tell the story of knowing land over time” and “being completely, microcosmically within a place,” says Whitehorse.

The way the light begins to change when clouds gather in the distance and again as they pass overhead; shadows moving across the land; the colors of a rising or setting sun. All are part of her vast lexicon of symbols.

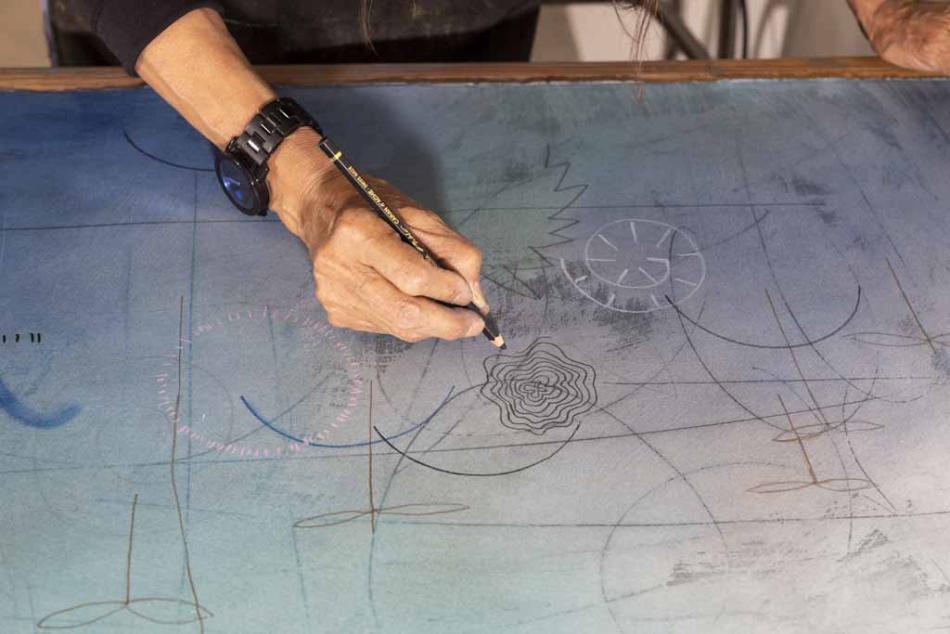

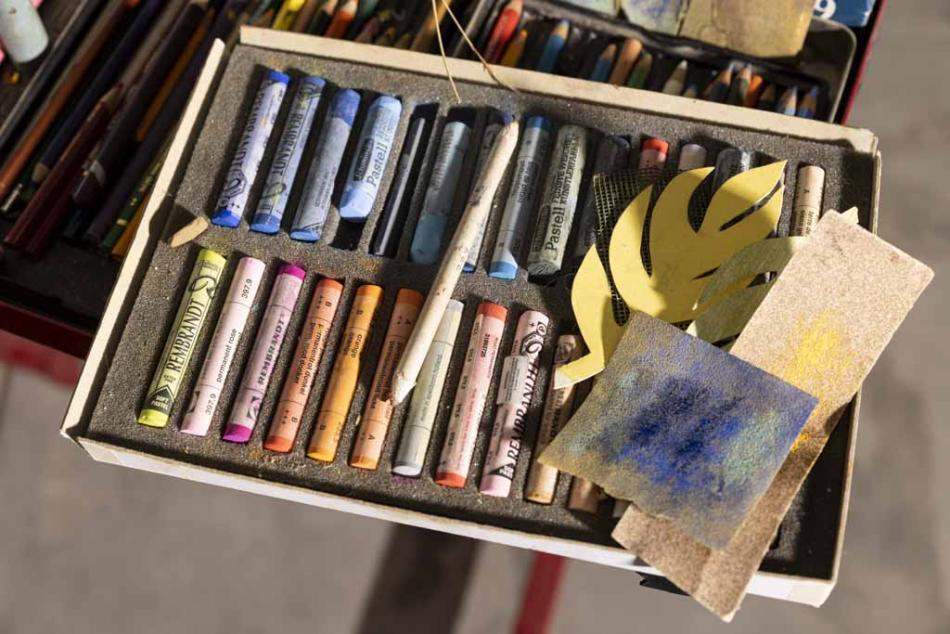

Whitehorse embellishes her large-scale oil paintings with pastel and graphite. She continually reorients them as she works, making distinctions such as “top” and “bottom” virtually irrelevant.

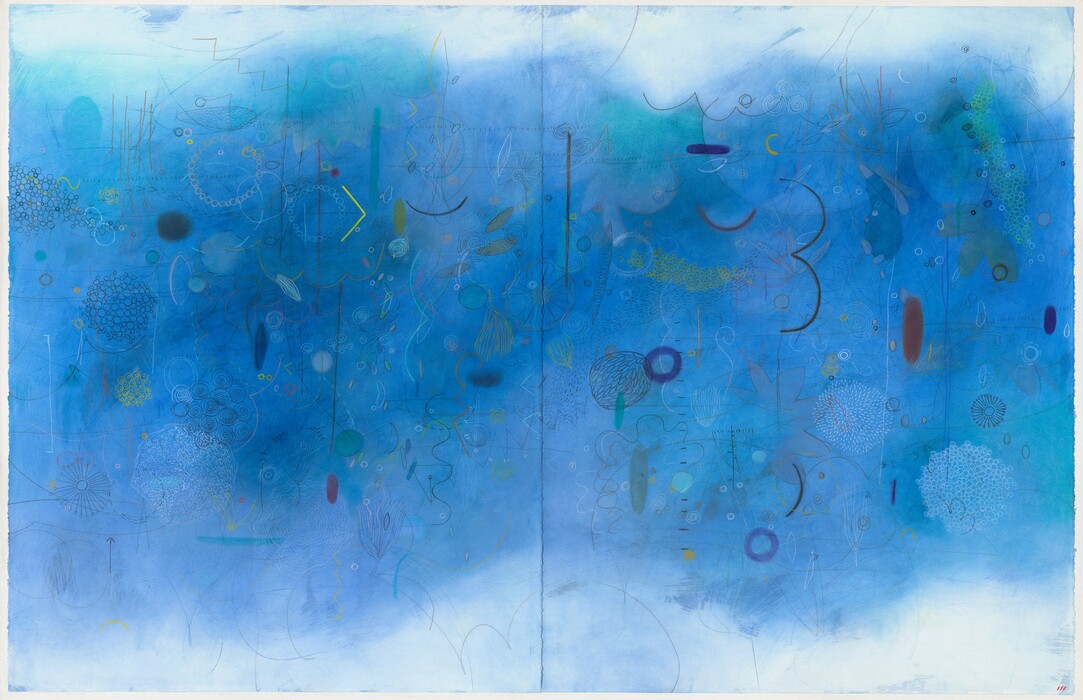

Fog Bank, a 2020 mixed-media painting rendered in celestial shades of blue, is one example. Its orientation is never quite discernible, yet it is still effectively composed. (The painting is now in the National Gallery’s collection.)

Whitehorse’s works celebrate the most unassuming of nature’s designs: a dry seed pod, grains of pollen, the quick movements of a water skeeter skirting the surface of a pond, animal tracks pressed into soft, damp mud.

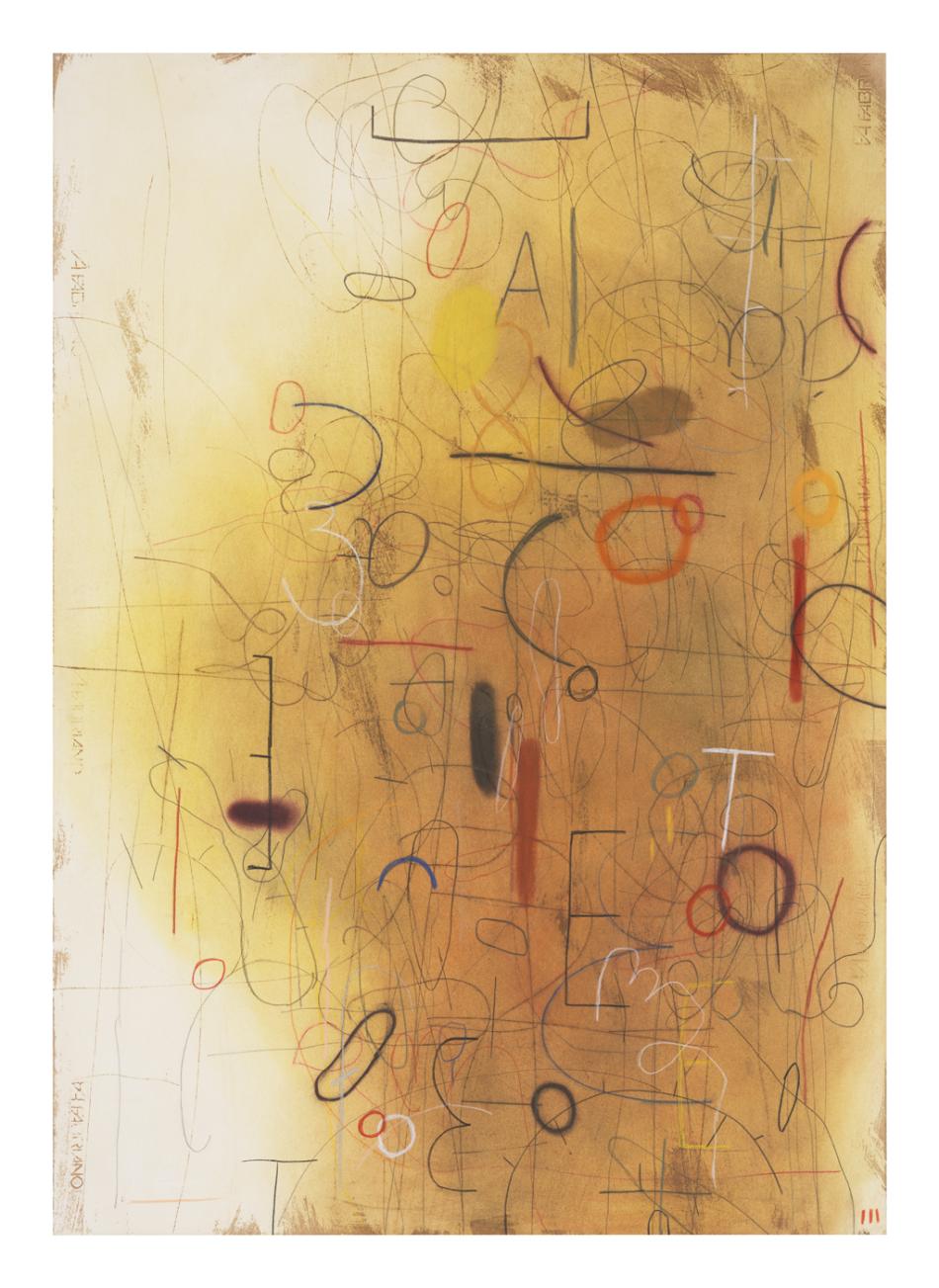

Her art has never been overtly political. But her 2015 triptych Outset, Launching, Progression responds to the long history of resource extraction and fracking on Navajo lands. Like many of her paintings, the work is done in shades of muted and vibrant yellows and golds. It reflects Whitehorse’s belief that maintaining a body-mind-life-nature equilibrium requires us to live in the good graces of Mother Earth. “What we do to the land comes back to us,” she says.

Whitehorse’s work speaks of and to her close relationship with the land and her Diné cultural heritage. It draws us into places that may be out of the ordinary in our daily lives—mysterious land formations, ethereal waterscapes, unknown skies. But these places are familiar to us in a nonmaterial sense. They center us in the spiritual and connect us to the sacred.

You may also like

Article: Mark Klett's Rephotography of the American West

How the photographer’s journey tracking down views from 19th century photographs altered the writer’s understanding of space and time.

Article: Artists Who Expand Views of the Southwest

You may know Georgia O’Keeffe, but have you heard of Tonita Peña? Learn about the many artists inspired by the Southwest.