Art that Represents, and Misrepresents, the US-Mexico Border

The 1,951 mile–long border between the United States and Mexico has long been contested and politicized. As discussions of borders have become increasingly heated in recent years, many images from this region have gone viral. Traveling the globe in seconds, they often reach people who may know nothing about the US-Mexico border.

Since, perhaps naturally, we gravitate toward the spectacular and shocking, images and stories of violence and turmoil tend to spread faster. Taken together, they portray a dystopian, incomplete story of the region.

On the surface, the border is dry and inhospitable. However, it is home to millions of people who work, study, and raise families. Unfortunately, images from the region leave out the human nuances of our daily lives.

What role does visual art play in this dynamic? Artists have documented contemporary life since before mass media or even written records. They capture and preserve information that otherwise would be lost to time. And when works of art then make their way into museum collections, they assume a more prominent place in our history.

The Border in the National Gallery’s Collection

The National Gallery of Art, as an example, is one of the most influential cultural institutions in the US. Its massive collection includes works from all over the world .

If we search the National Gallery’s collection for the term “border,” dozens of results show up. Most of them are picking up on a keyword in the description that refers to the artistic frame designed around an ancient artwork, such as this painting made by Paolo di Giovanni Fei circa 1400/1405. Artworks that refer to political or national borders are limited.

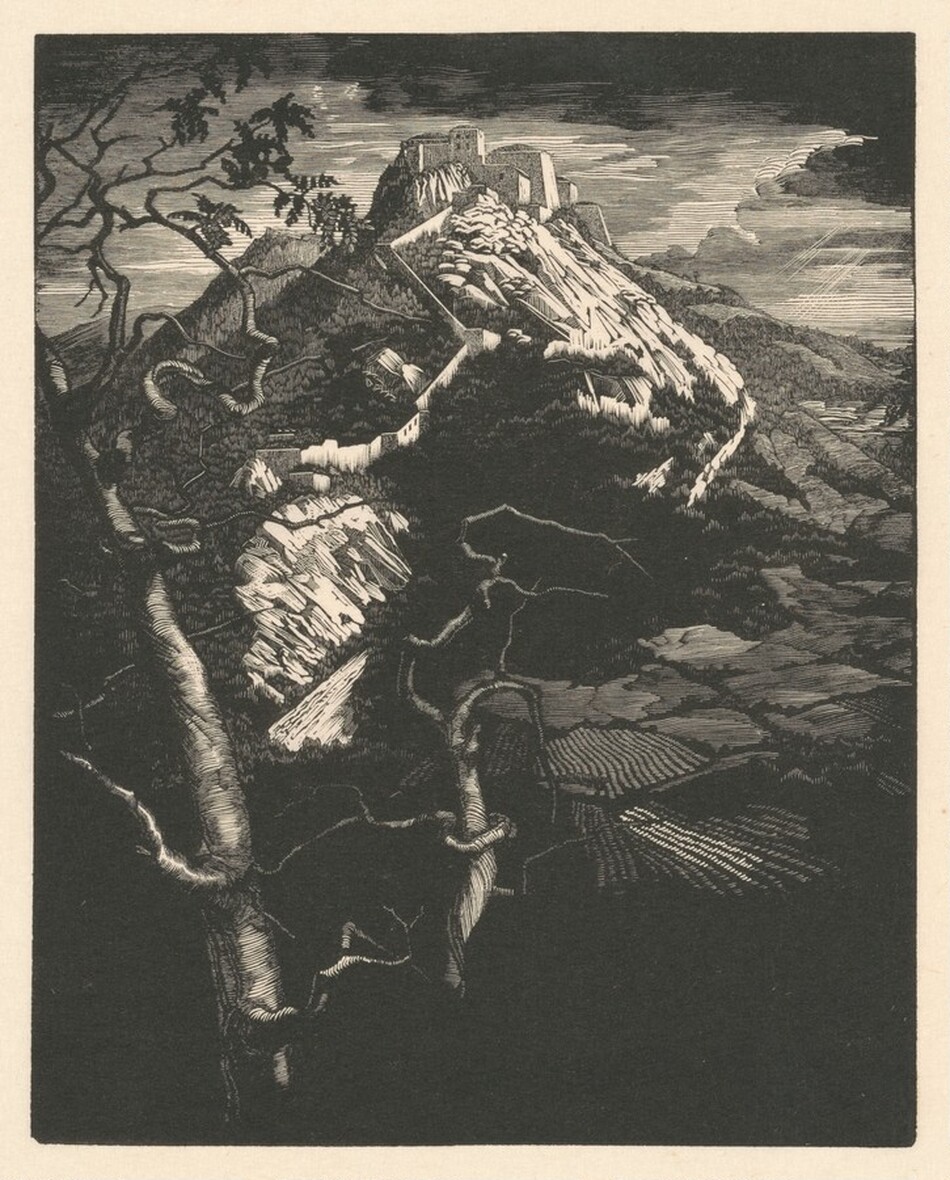

Works such as Grace Albee’s 1929 engraving Guardian of the Border present borders as places to be defended. Hunting Along the Mexican Border, made by photographer Ed Erwin between 1920 and 1929, shows a wild natural space with no human presence.

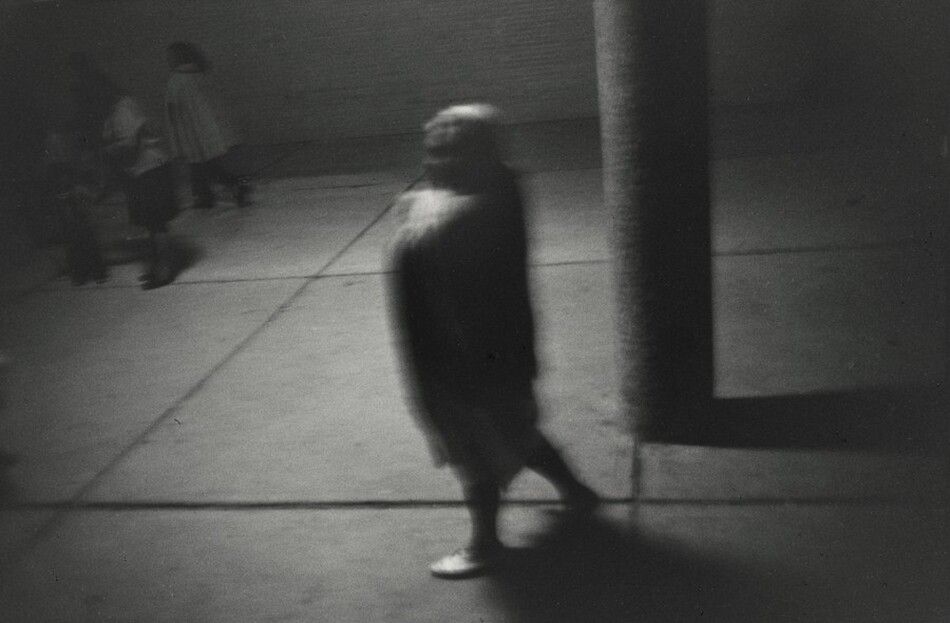

If we use the terms “El Paso” (in Texas) or “Juárez” (in Mexico) to narrow our search, only a handful of results come up. Just one of them directly refers to the border cities: Edward Garza’s 1972 photograph Juarez, Mexico. The blurry, black-and-white image portrays four people moving through what we can assume are the streets of the city. The dreamlike photo plays into the idea of Juárez, and borders, as liminal, surreal places to be traversed, but not inhabited.

Among more recent acquisitions by the National Gallery, we find the work of renowned photographer Richard Misrach. The collection includes his photographs Southwestern and Hawaiian landscapes as well as of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation in New Orleans. There is also a 2013 series of photographs at the Lower Rio Grande National Wildlife Refuge in Texas.

Called Border Patrol Target, these images show paper human silhouettes with holes from gunshots. From the title we know that they were used as targets by agents of the US Border Patrol. This work is not unusual: socially engaged and political artists often use their art to highlight contemporary issues. Perhaps Misrach’s goal is to bring attention to the militarization of borders, or the brutal treatment of migrants by US authorities. But how do these photographs affect our perception of the border?

If you were trying to understand the region only through the National Gallery’s collection, how would the images shape your ideas? Do they make you empathize with the people living there? Do they make you want to visit? Do they provide you with a complete understanding of the border?

Recently, artists living on the border have been using their creative practices to counter mainstream narratives and humanize borderlanders. Given their personal, lived experiences of the region, their works often reference its social issues and political dynamics. Fortunately, they do so with subtlety and nuance.

Haydee Alonso's Shifting Relationship with the Border

Haydee Alonso was born and raised in the El Paso/Juárez border and holds both US and Mexican citizenship. Her work, which includes jewelry, installations, performances, and images, explores the dynamics of a binational experience. We can see how her understanding of the border changes over time by looking at the evolution of her art.

With a background in metalsmithing, Alonso creates jewelry that also functions as tools to encourage us to think about the dynamics of human interactions. She designs jewelry pieces that are only activated if two or more individuals are involved.

Inter-acting is a series of copper and brass objects Alonso created in 2015 that incorporate aspects of traditional jewelry. It is almost impossible for only one person to “wear” them. The only way to wear the pieces is by interacting with another person. Alonso is referring here to the adaptation between humans and their environment. Her work reflects our flexibility in adjusting to different circumstances.

When she created Inter-acting, Alonso imagined the border as a porous place filled with possibilities. This way of looking at the border came from a position of privilege. As a citizen of both the US and Mexico, she was able to cross the border, going back and forth without problems.

Recently, Alonso’s idea of the border as a place of full of possibilities became more complex. Events such as the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the daily life of thousands of border-crossers.

In her 2021 series COZEN, the artist continued the idea of tools for interaction. This time, however, the work reflects more fractured human relations. These objects also require two people to “function,” but the interaction is broken, difficult, and sometimes nonexistent.

Artist Haydee Alonso connects two women to ‘Bad’ Hyphens Separate; ‘Good’ Hyphens Attach (2023) during a performance at the El Paso Museum of Art. Photo by Miguel Vargas.

In 2023 Alonso created ‘Bad’ Hyphens Separate; ‘Good’ Hyphens Attach, a thin brass bar that is meant to be worn as an earring. Once again, this earring has to be worn by two people. One wearer cannot progress without the other, and if they try, damage might be inflicted on both.

‘Bad’ Hyphens Separate; ‘Good’ Hyphens Attach recently entered the collection of the El Paso Museum of Art. Through this work, Alonso encourages us to think about how humans rely on each other: one cannot exist without support from others. Although sometimes working together is difficult, it is necessary to move forward in large communities, regardless of arbitrary political boundaries.

Alonso Robles's Views of Everyday Juárez

Juárez-born and based painter Alonso Robles also reflects on his lived experience on the border—in this case, it is as a young man with only Mexican citizenship. Juárez’s major industry is manufacturing, and new factories lead its urban growth. New houses are usually built around factories and sold to laborers through government programs and loans. The houses have gotten smaller through the years, and they follow a cookie-cutter design.

In his series Oasis: La casa de nadie (Oasis: No one’s Home), the young painter portrayed his experience living in social interest (subsidized) housing in his hometown. Robles shows us the intimate moments he shares with his family. Painting the series during the pandemic, he depicts the experience of sharing a space for a long time and its implications for family relations.

In his exhibition Segunda mano, segunda casa (Second hand, second home), the artist explored the source of his family’s livelihood. The border is usually portrayed as a harsh place, but in reality it offers a lot of economic possibilities. For years, the Robleses have imported second-hand merchandise from the US to sell at flea markets in Mexico. The artist shows his family’s economic relationship to the border in an imaginative way. In his paintings we see how the dynamics of a political border can offer opportunities to procure a dignified life. At the same time, Robles puts real humans who live at the border in the center of his works. His paintings incorporate portraits of his family, including his mom and grandmother, engaged in activities related to their work.

More recently, Robles has created art that explores quinceañeras—parties thrown to celebrate the 15th birthdays of girls. They are prevalent rites of passage in Latin American cultures, including in the US diaspora. In his new work, Robles considers how the experience of quinceañeras teaches young boys to be men, or gentlemen. By depicting an event that is common across countries and cultures, he helps us connect to others through shared experiences. Robles’s works have made their way into several important private and institutional collections in Mexico.

Whether it’s through breaking news or works of art, images shape our perception of places we do not personally know. They can also limit our understanding. More accurate representation—and, even better, self-representation—helps us develop a fuller perspective on border communities. We can start by being aware of what we are and are not seeing as we sort through the never-ending images at our fingertips.

You may also like

Article: Emmi Whitehorse Paints the Harmonies of Her Homelands

How the Diné artist's serene paintings "tell the story of knowing land over time."

Article: Sentinels and Sprawl: Photographs of the Saguaro Cactus

As the presence of humans changes the Sonoran Desert, photographers capture the impact on the saguaro cactus.