Ruth Asawa’s Little-Known Experiment with Printmaking

Ruth Asawa arrived in Los Angeles in September 1965 ready to experiment.

The Japanese American artist’s mentor Josef Albers had recommended her for a fellowship at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, which invited artists to explore printmaking with help from expert printers.

In her short two months at Tamarind, she would make an impressive 54 lithographs. The National Gallery’s collection includes all of them. Today, Asawa is best known for her sculptures. You can even mail your next letter with a stamp featuring one of them. Her brief but fruitful period of experimentation with printmaking has been largely forgotten.

Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa in her dining room with tied-wire sculpture, 1963.

© 2023 Imogen Cunningham Trust / Courtesy www.imogencunningham.com

Artwork © 2023 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy David Zwirner

Ruth Asawa’s Famous Sculptures

Asawa was a lifelong artist. As a young girl, she would draw forms in the soft soil on her family’s farm.

As a teenager, Asawa was one of the more than 120,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated across the American West. She was first held at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in California and later transported to Rohwer internment camp in Arkansas. At Santa Anita, Asawa drew with artists who had been working at Walt Disney studios. At Rohwer, Asawa was the high school yearbook editor and drew caricatures of her teachers and classmates.

By the time she arrived at Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Asawa had been working as an artist for decades. She had recently exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, showing her paintings, drawings, and sculptures.

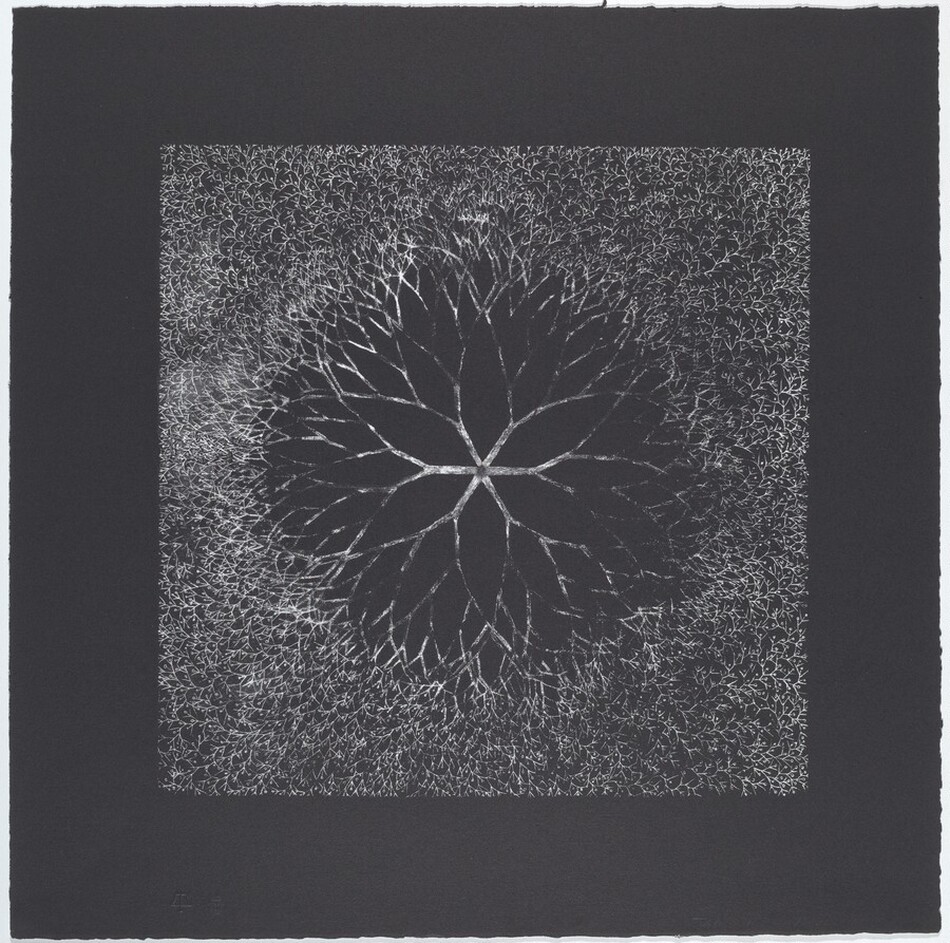

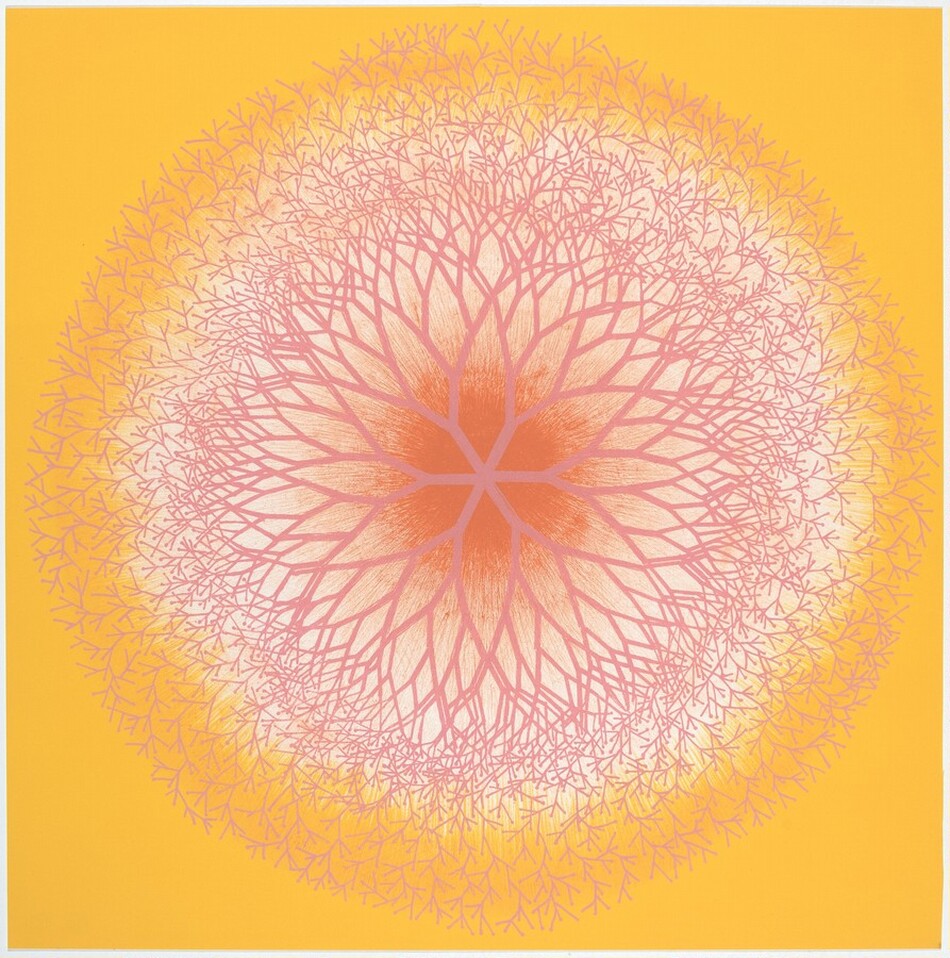

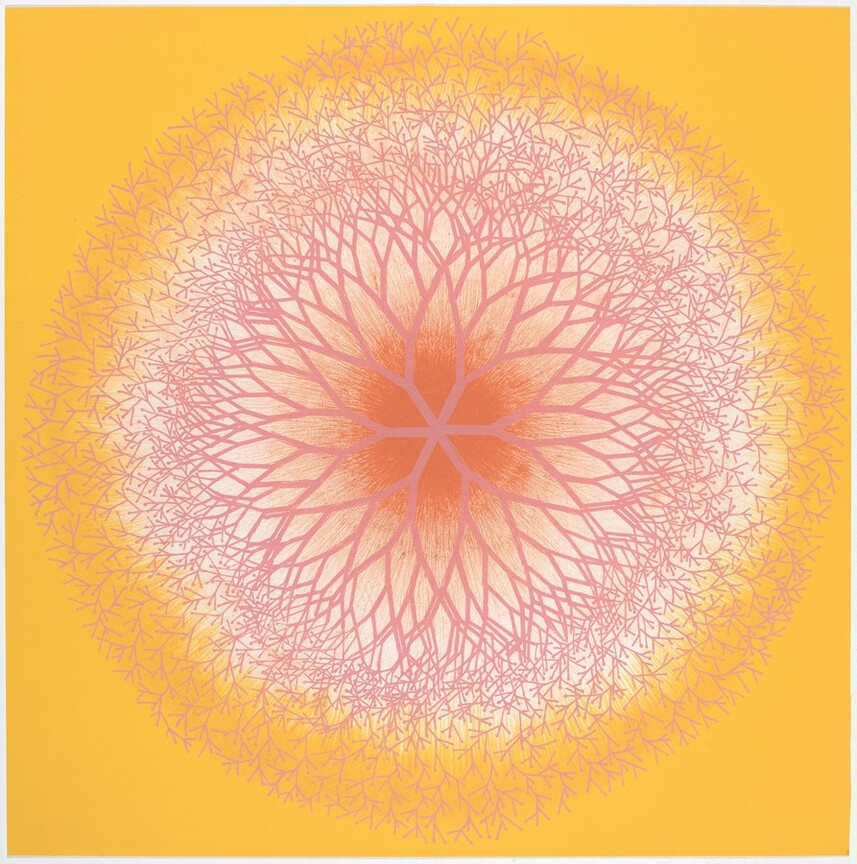

“Sculptures” doesn’t really begin to describe them, though. Made from looped wire and seemingly weightless, Asawa’s organic semitransparent forms seem to be paused in motion. They are like floating creatures swimming through space. The artist built on a traditional wire basketmaking technique she had learned during a trip to Toluca, Mexico. In 1962, a few years before her fellowship at Tamarind, she had begun making tied-wired sculptures that look like trees with bare branches. These were inspired by a desert plant that her friends had given her.

And in fall 1965, Asawa would try her hand at something new—printmaking.

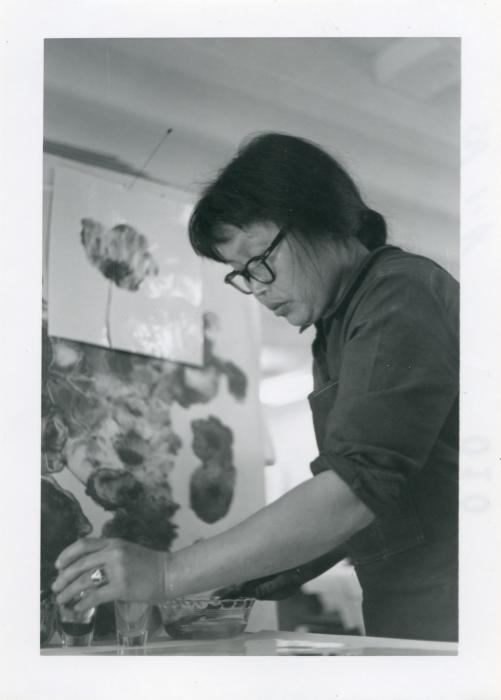

Ruth Asawa at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, 1965.

Courtesy Tamarind Institute and University of New Mexico Libraries, Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections (CSWR #000-574-0832).

Ruth Asawa at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop

Artist June Wayne founded the workshop in 1960, hoping to remove the logistical barriers to lithography and encourage artists to embrace the medium. Lithography was expensive and challenging—it required special materials including large, heavy stones and printing presses.

Her plan worked. Over the 10 years Wayne led the workshop, more than 150 artists explored the medium for the first time. These included some of the leading artists of their day: Louise Nevelson, David Hockney, Gego, Philip Guston, Ed Ruscha, Rufino Tamayo, Charles White. Several participants went on to found other lithography workshops, further spreading interest in the technique.

Asawa got lucky. The other artist scheduled to be at Tamarind at the same time never showed. She had the undivided support of the workshop’s seven talented printmakers. She was clearly a quick learner—in her short two months there, she made an impressive 54 prints. That’s more than 6 different designs and prints a week.

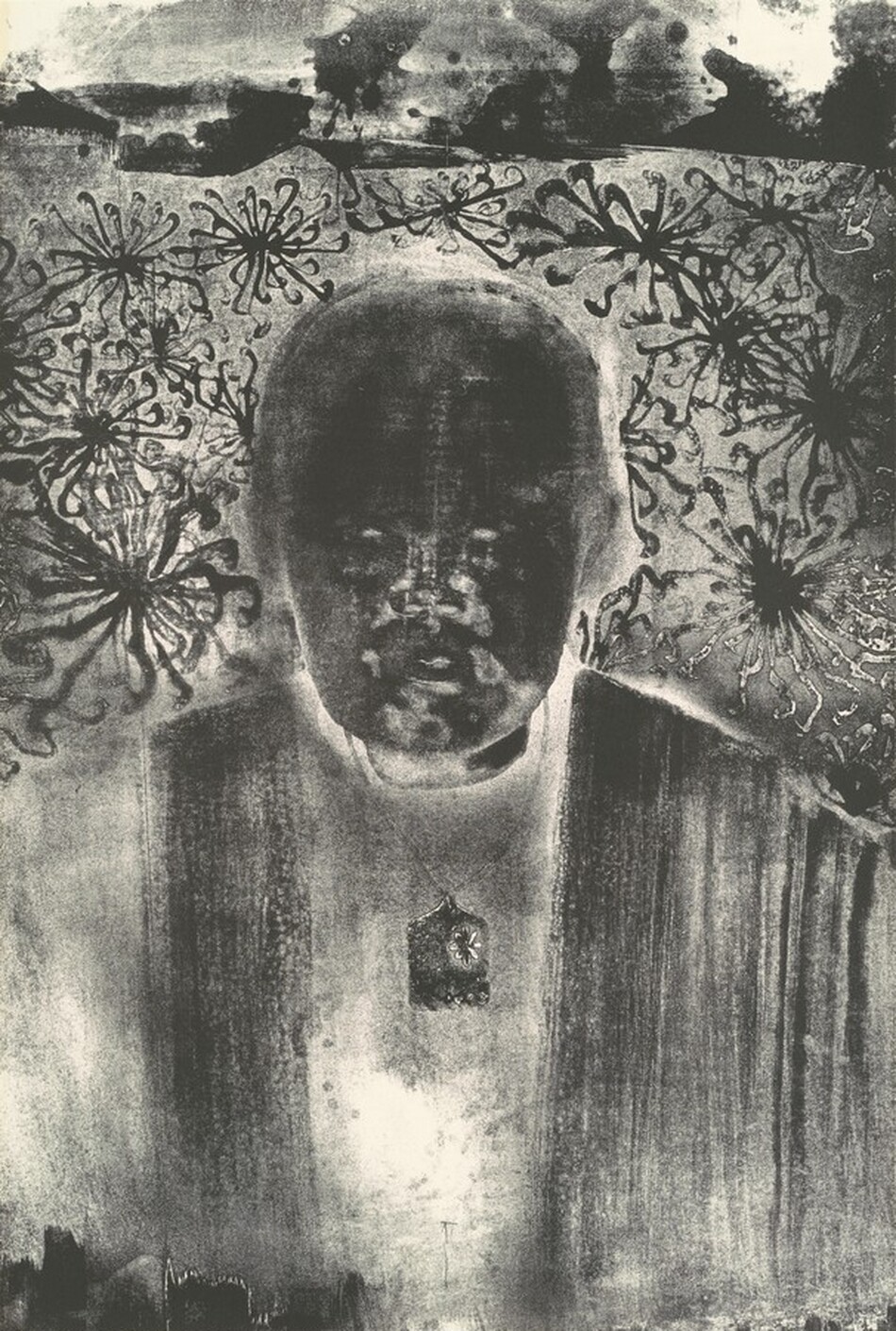

Asawa seemed to have two things on her mind while in LA—flowers and family. It was the longest she had ever been separated from her six children who were ages 5 to 15 at the time.

In one portrait, Xavier (her eldest) looks directly out at us with a serious expression. In another, we see Hudson (the third eldest) in profile, focused on a book. Adam (the next youngest) sucks his thumb while sleeping next to the family dog, Henry. Paul (the youngest) looks almost sad, his face sandwiched between two puppets or dolls.

But these aren’t merely family portraits. They’re also experiments with pattern and texture. Note the crosshatched lines on Hudson’s checkered sweater. Adam and Henry’s portrait, too, is full of different patterns.

Ruth Asawa's Process and Prints

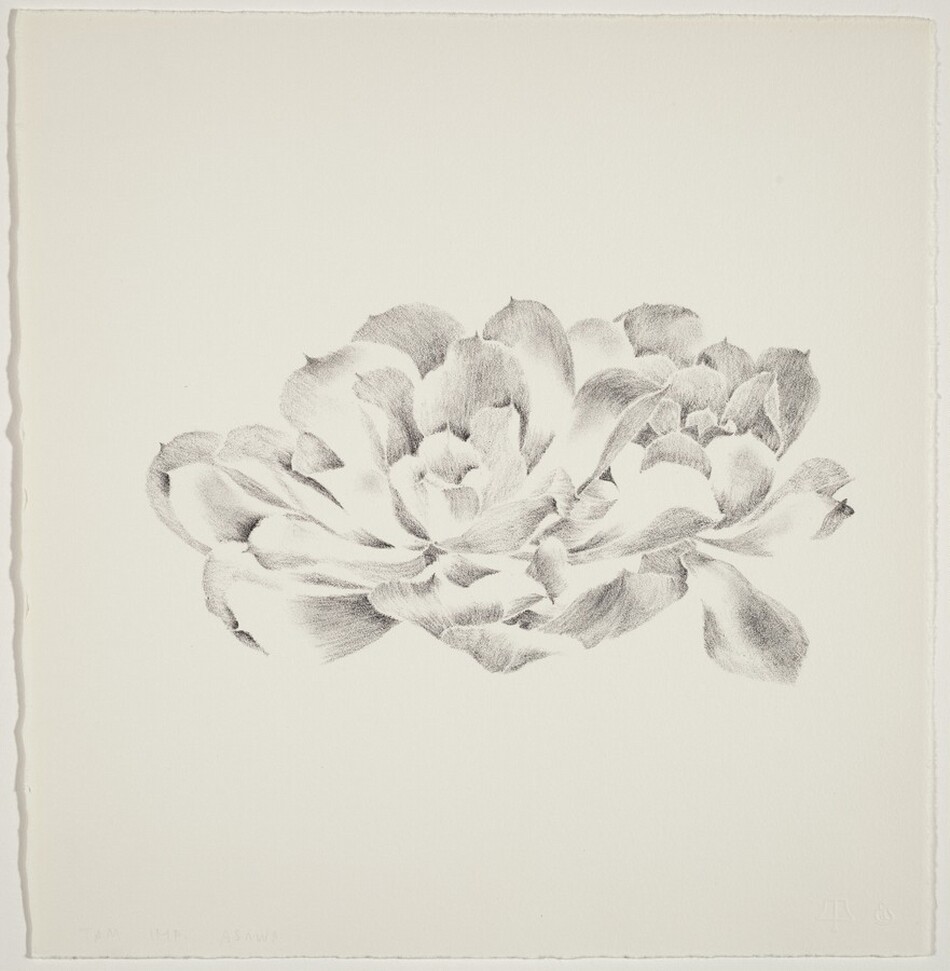

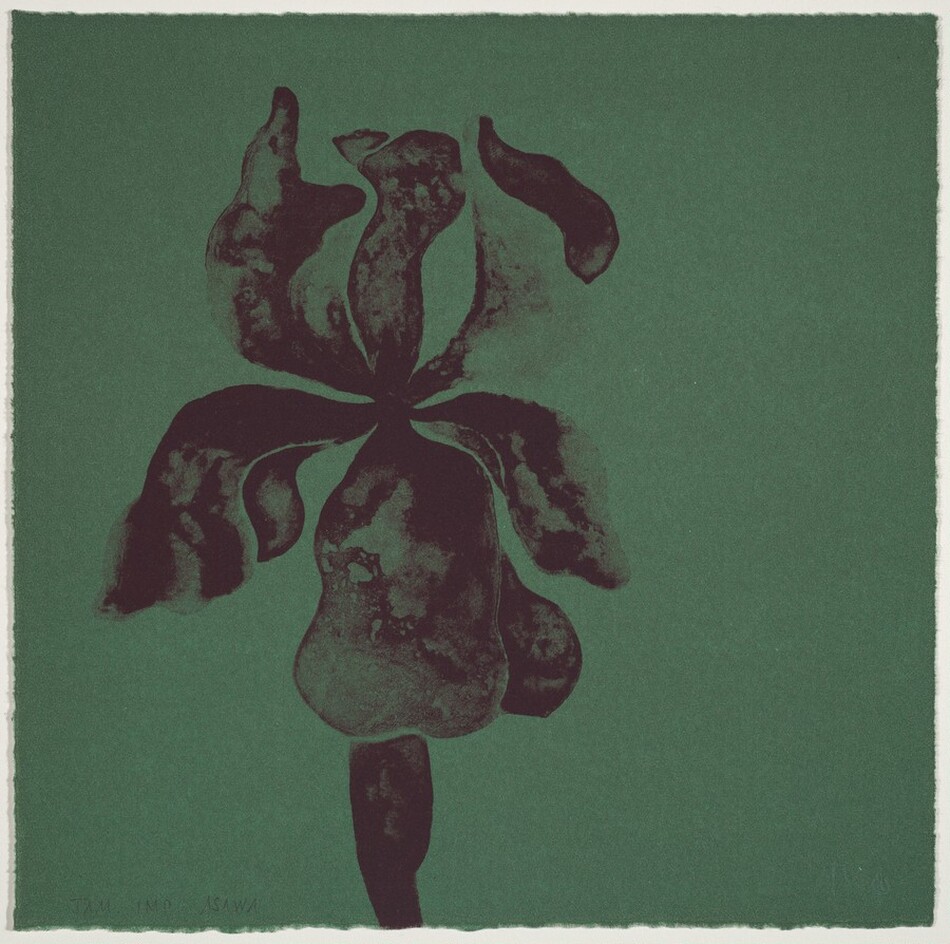

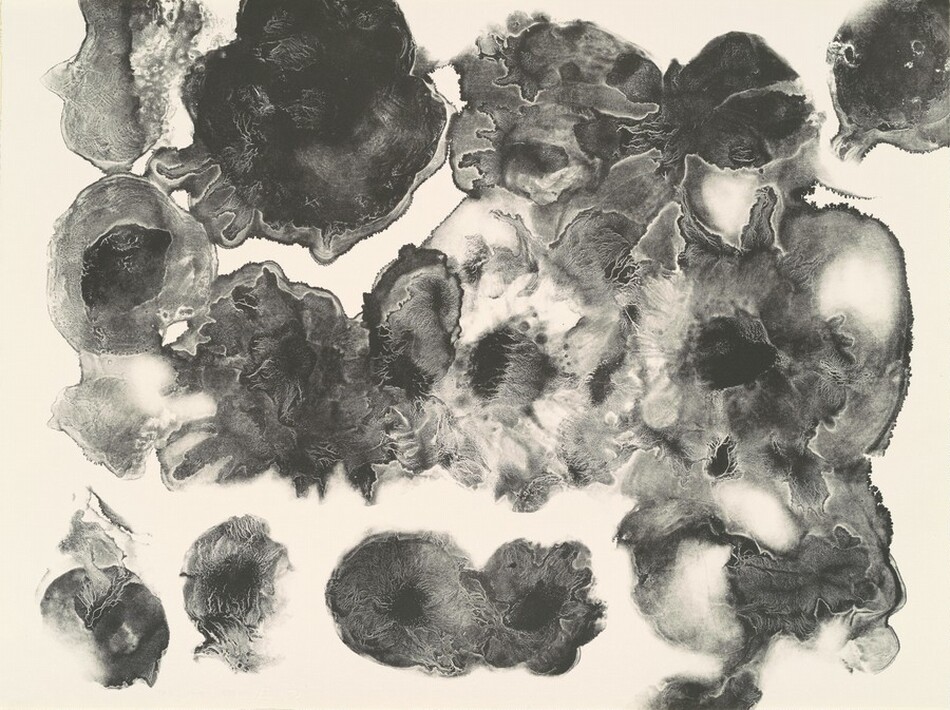

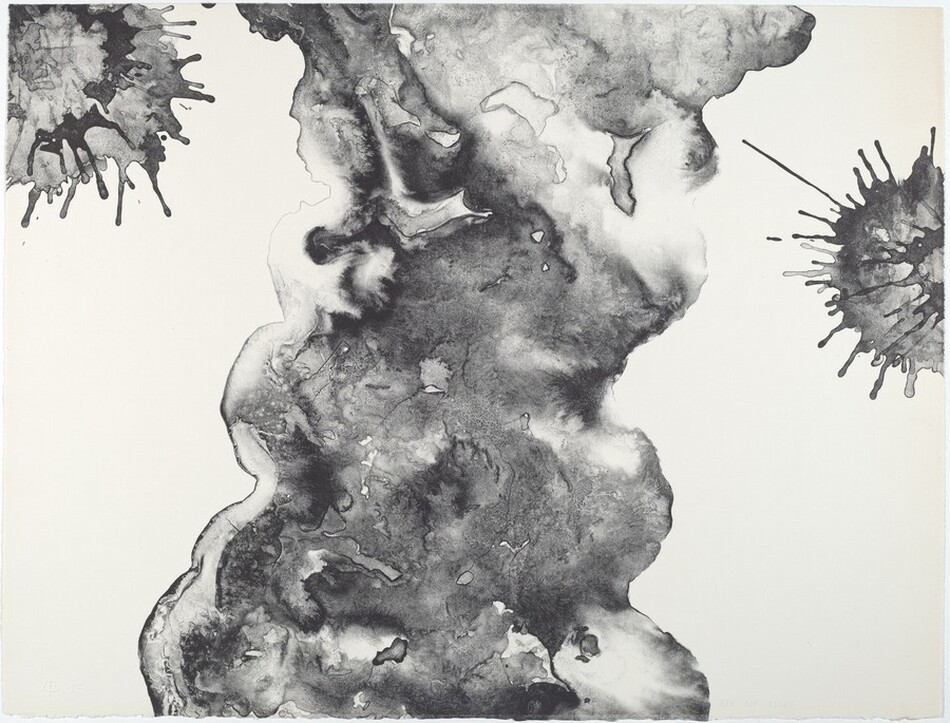

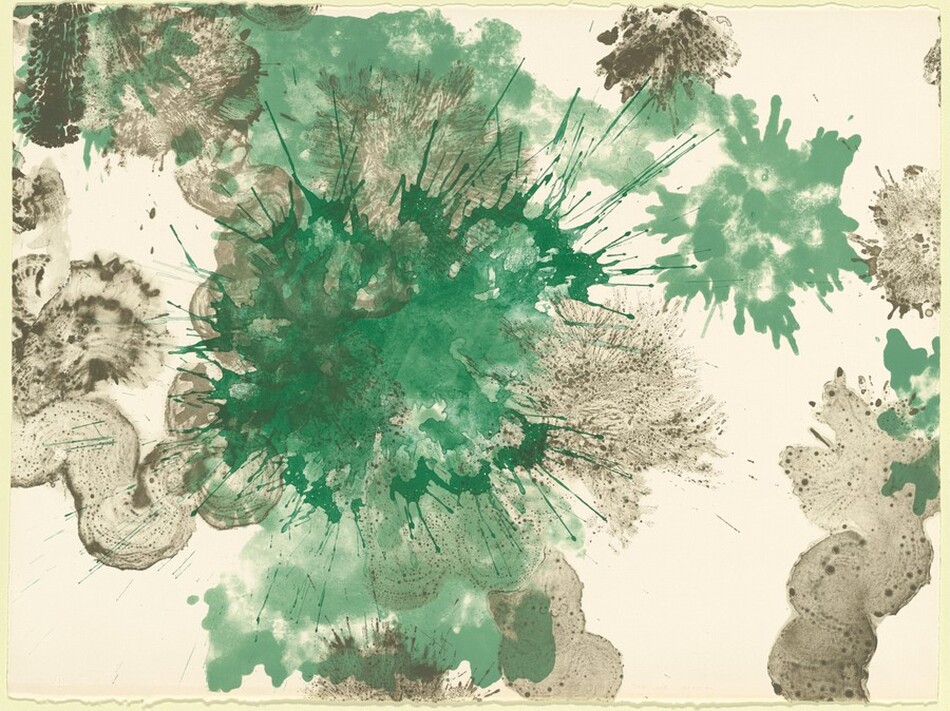

Most of the prints Asawa made at Tamarind started with drawings. She would use a special pencil, crayon, or liquid ink to create a design on a flat block of limestone. Next, Asawa and the printers layered various materials to the surface to adhere the design to the stone. They then applied water to the stone using a sponge and rolled ink over the surface. Wet stone would repel the oil-based ink, which would only stick to the greasy lines of the drawing. Then a sheet of paper was laid face down on the stone and run through the printing press. To add other colors, Asawa and the printers would have to repeat the same process on different stones, carefully making sure the image is aligned each time. This exacting method is what makes Asawa’s output at Tamarind so impressive.

Her radiant Desert Plant echoes the forms from her tied-wire sculptures. Pink branches or roots extend from a red center toward a marigold background. In lithographs like Flowers V, Asawa tested out liquid tusche, a material that looks like a watercolor or ink wash. In other prints, she delicately layered coral, green, and purple inks.

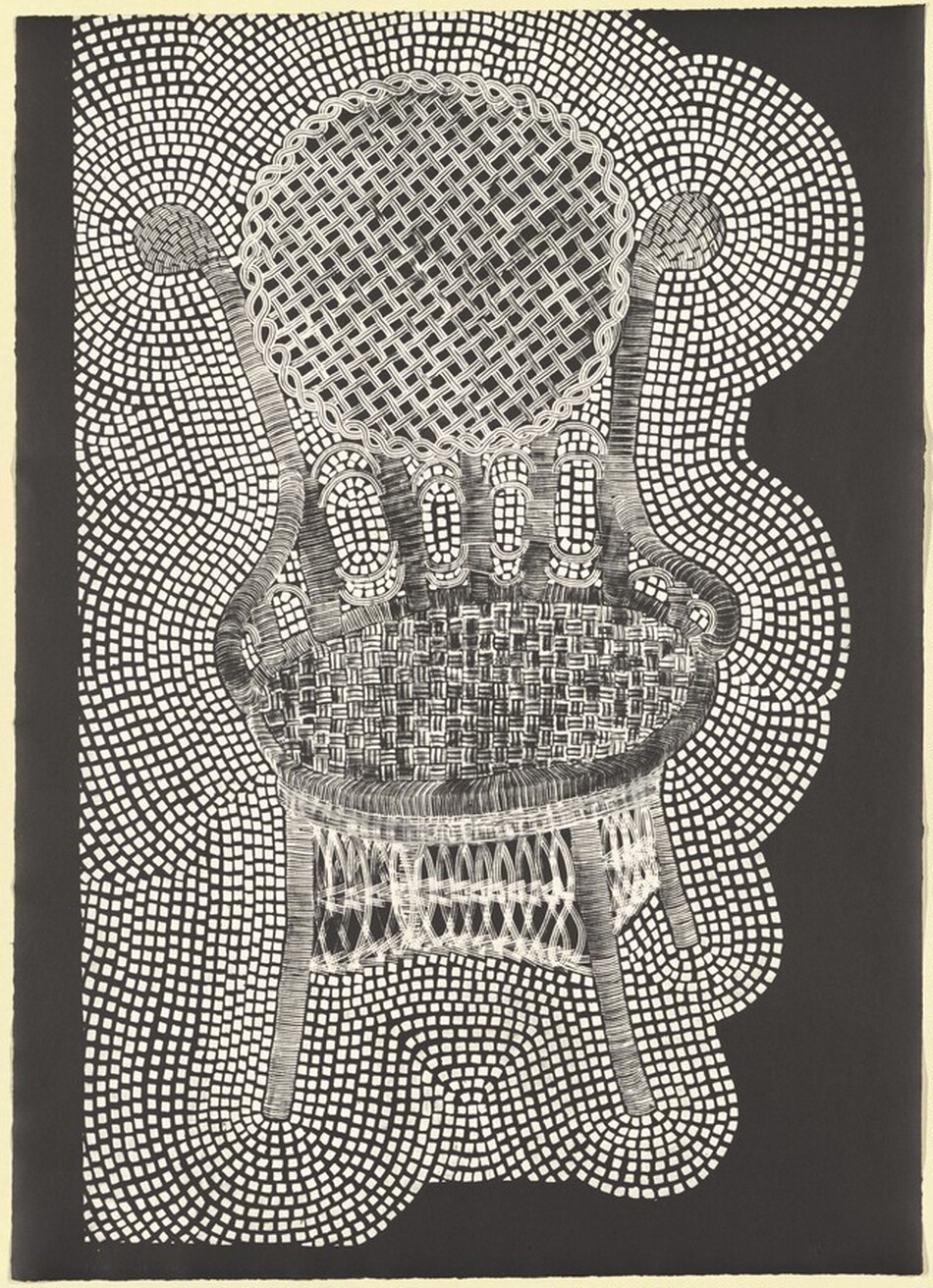

Asawa didn’t leave weaving behind when she came to Tamarind. She just found a way to weave on paper. In Chair,we see the chair’s circular back, its wicker lattice and braided edge. The chair’s legs and arms appear to be wrapped with a thicker cane, while its seat is cross-woven. Small horizontal marks radiate from the chair, filling all but the right side of the paper. Has a chair ever been so dazzling?

In October 1965, Asawa returned to San Francisco, leaving lithography behind. While it spanned only several months of her long 60-year career, her time at Tamarind left an impression. “The excitement of printing has not left me, but I know it would take another lifetime to do it well.”

You may also like

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.

Article: From Old Car Tires, Chakaia Booker Reveals Beauty and Devastation

Transforming discarded tires into monumental sculptures, the artist reflects on the environmental impact of our daily commutes.