A Portrait of Gay and Lesbian America 30 Years On

“It’s the late 1980s. I’m in my 20s. And I’m first realizing that I’m gay,” Nancy Andrews recalls. “It kind of turned me on my head.”

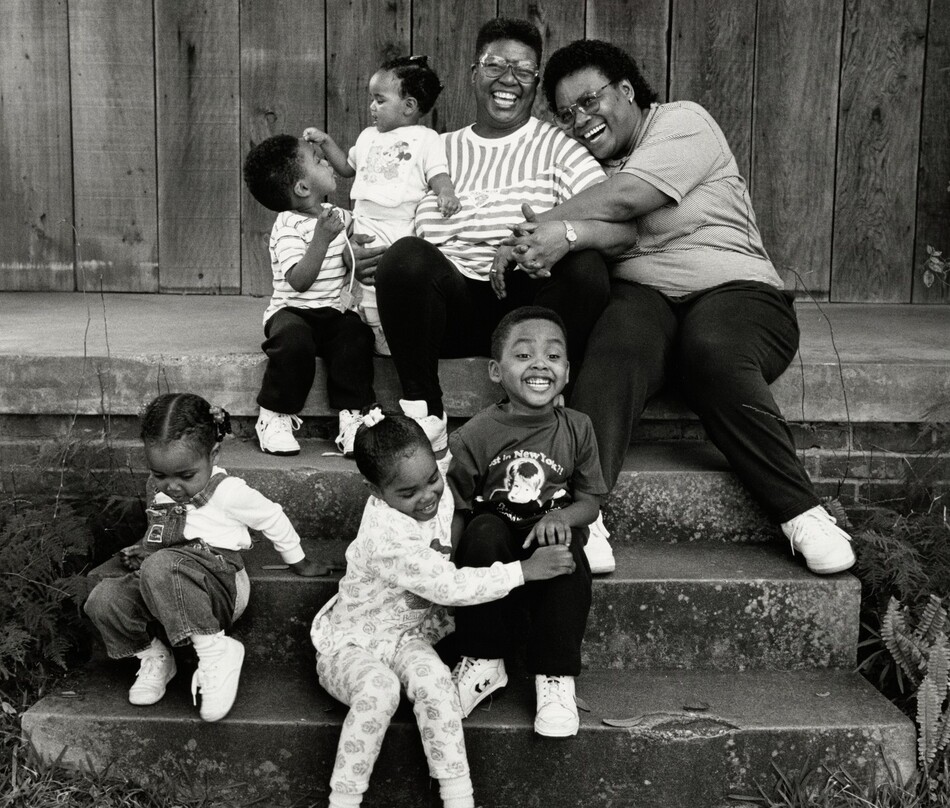

Andrews published FAMILY: A Portrait of Gay and Lesbian America in 1994. The book and accompanying exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art brought together Andrews’s photographs from more than five years of traveling the country, interviewing and photographing gay and lesbian Americans. Andrews has donated many of the works in FAMILY to the National Gallery. She talked with us on the 30th anniversary of its publication.

How did you decide to make FAMILY?

I grew up in a rural community in Virginia. A very loving community and a Southern Baptist tradition. Gays and lesbians were invisible to me.

Certain people felt comfortable enough being out, but you didn’t necessarily know lots of gay people. You might have known spinster aunts, uncles, or cousins, but it wasn’t talked about.

This work was really a process for me to find out: Who am I? Who are my people?

Individual pictures are of the person in the picture. But the body of work is also a picture of the photographer.

And how did you find people to photograph?

There was a thing called the “Gay Yellow Pages.” And I subscribed to gay newspapers thriving around the country. If I had a trip for my job at the Washington Post, I would add vacation days to work on my book.

So I’d use the newspapers, the Gay Yellow Pages. Or I’d call organizations, tell them what I'm trying to do. I would say, “Who’s the oldest gay person, you know?” If it was near a holiday, I might say, “Do you know somebody celebrating Ramadan who would let me photograph?”

And people would come up with things I hadn’t asked for. One time I was in New Orleans asking for a family celebrating Sukkot. Someone answered, “I don’t know. But I do know a gay Holocaust survivor—will that do?”

There is a lot of diversity among your subjects. How did you choose them?

I realized I had an obligation. If the work was going to help someone like me, it could very easily help someone who was different from me. Didn’t look like me, didn’t talk like me, was a different race or religion.

Yet still, it’s not everything. I had to be very narrow, in a certain sense. It was really just looking at gay men and lesbians—or that part of someone’s life.

And what was it like to see into that part of people’s lives, which can be rather intimate?

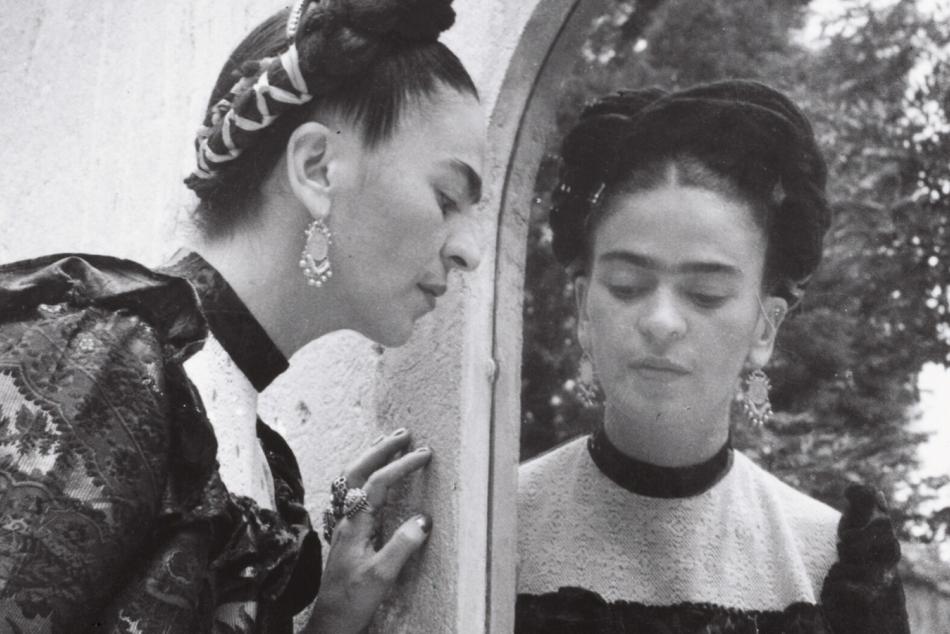

To go inside people’s homes, inside people’s workplaces, inside their hobbies—that is more of everyday life. You've got people who wear drag, but maybe they're not in drag in this picture. (Or maybe they are and they're part of a Mardi Gras krewe!)

To me there are two parts of photography or any art. The act of creation has its own satisfactions. The puzzle is right in front of you: how to use the light or the composition to make, some would say, order out of the chaos. Then there's the other element: to show it, to share it. My price of admission into your home is that I turn around and show it to somebody else.

In Maine, I met Mary Courtland. This woman lived alone, though I also met people helping take care of her. She looked like anybody's grandmother, but she'd never had children. She had been kicked out of a convent as a young novitiate for kissing another nun.

Now she was 89, and she was just sitting there with her purse waiting to go to the grocery store. Hopefully, someone will see their aunt in that picture—or maybe their grandmother. Or it’s the oldest gay person they’ve ever seen, period.

Were some people you approached uncomfortable with being photographed?

Everyone who agreed to be photographed, they were brave. On a certain level, everyone in the project was an activist just merely by being willing to be photographed.

In the interviews, people would mention that their parents didn't know. And I asked, “What if they see your picture?” They’d say, “Oh, I guess they'll know, then.”

The yearning that I felt to find people, other people also had that urge. They realized that we're this invisible group of people. The one way for us to have our rights and to not be dicriminated against is to lose our cloak of invisibility.

There are photographs of people with their partners and their friends. But there are also many people represented as individuals, by themselves. How did you choose whom to portray on their own?

Sometimes you think you’re photographing just one person, and now there are five people in the room. Some were working together as a couple. Or I might have called them for the one, but they wanted to be together.

But it’s also much harder to make a dynamic collection if you always have one person in the photograph, or always have two people, or always have a group. By varying the number of people, I can show a gay fraternity versus Mary Courtland sitting in her kitchen. That is more dynamic. The variations help give it movement. I just don't want you to be bored.

When choosing which images to include, how did you balance those compositions against capturing something essential about your subjects?

The overriding idea for making the photographs and choosing what to include was being true to that younger version of me—or someone who wasn't like me, but was discovering that they were gay or lesbian.

There are pictures in the body of work that I don't really like. I feel I've failed as a photographer. However, I included them because I felt they spoke to someone who wasn't like me.

And sure enough, years ago, a woman came up to me at a book signing. She describes her favorite photograph. And I'm thinking, “Oh my god, she likes that photograph?” But she looks practically exactly like the person in it. And that was what was so beautiful. It wasn't there for me, it was there for her.

Did it ever come across differently from what you intended?

There's a great example that shows what's unique about the collection at the National Gallery. There is a couple that I photographed: Jean Mills and Carol Eichelberger. There’s only one picture of them in the book and the original collection. They are walking up the hill from their farm with chickens following them. I liked this picture the best—the way it felt like a farm.

But it was pointed out to me later that you might think that they did not want their faces shown. Anyone else whose face I obscured, it was because I needed to obscure it. But here that wasn’t the case at all. So I added a picture where you could see their faces to the National Gallery’s collection.

My ego wants it to be perfect photography. But it's not. It's messy. It's a journey that I was on.

Did this project shape your understanding of gay and lesbian identity?

Yes. It was interesting how people would help, even if they didn't feel they could be in the book. There was just a kindness and sharing.

I think we sometimes define ourselves by our differences, right? I saw myself: Okay, now I'm this gay person. That's what's different about me. And I thought that I'd be linked to all other gay people in that. But I found that, whereas that might be the first new adjective I would have picked for me, that wasn’t the case for everyone.

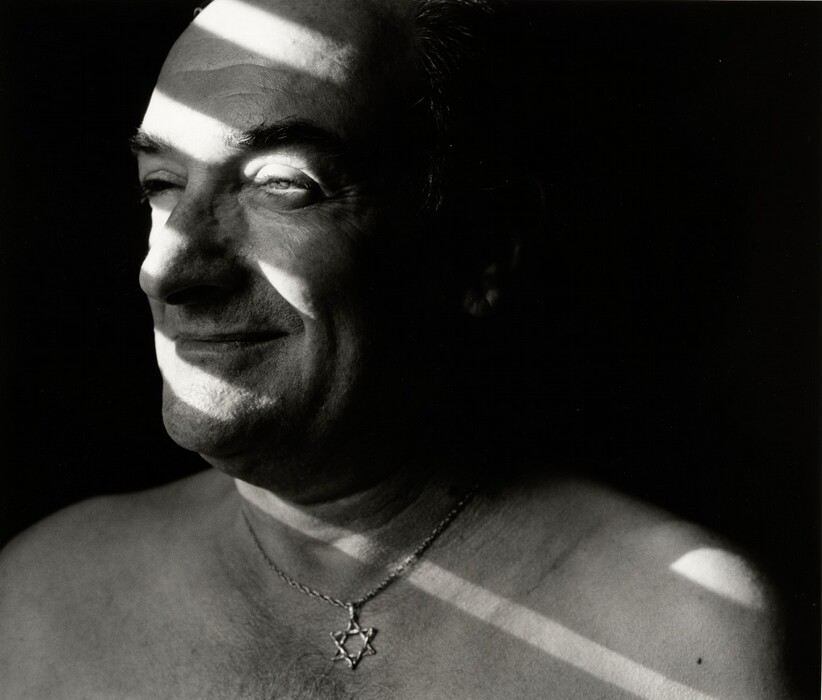

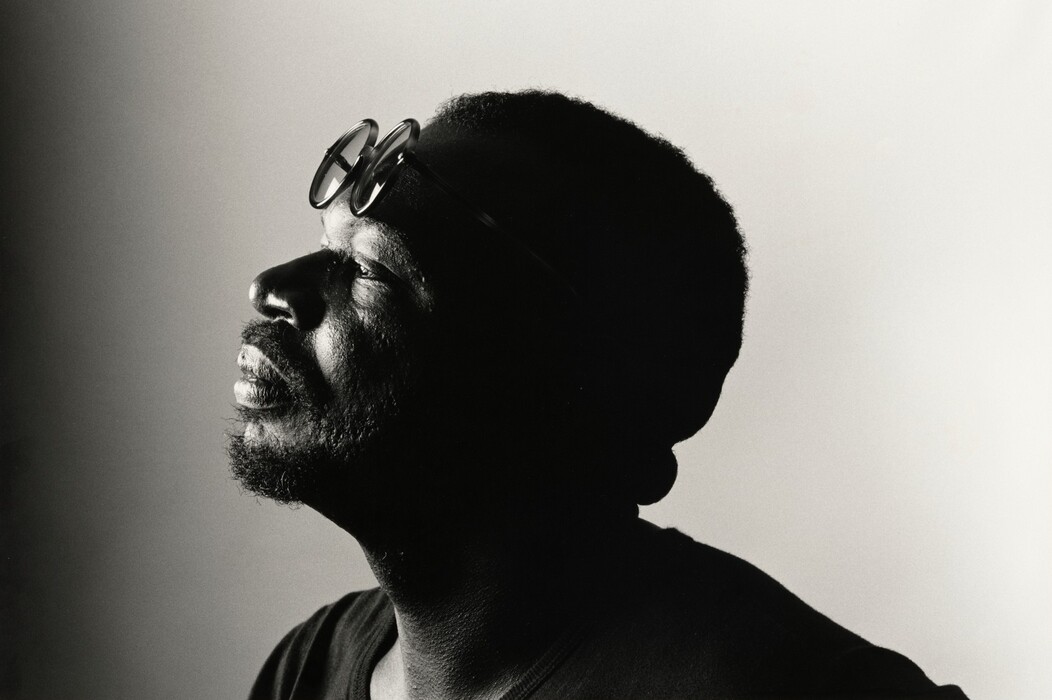

From my interviews I learned that different people had different circles of how they were connected or not connected to the world. Maybe the world treated them first as Black or as Jewish and then treated them differently because they were gay or lesbian.

In those interviews, there were certain questions I asked nearly everyone. I said, “What do you want people to see when they see your picture?” And I’ll point out Charles Gervin. He quite simply said, “I want them to see themselves.” So that’s also sort of the essence: that we are all more alike than we are different.

You may also like

Article: 15 LGBTQ+ Artists to Know

Discover the lives of 15 LGBTQ+ artists and their art, much of which you can see at the National Gallery.

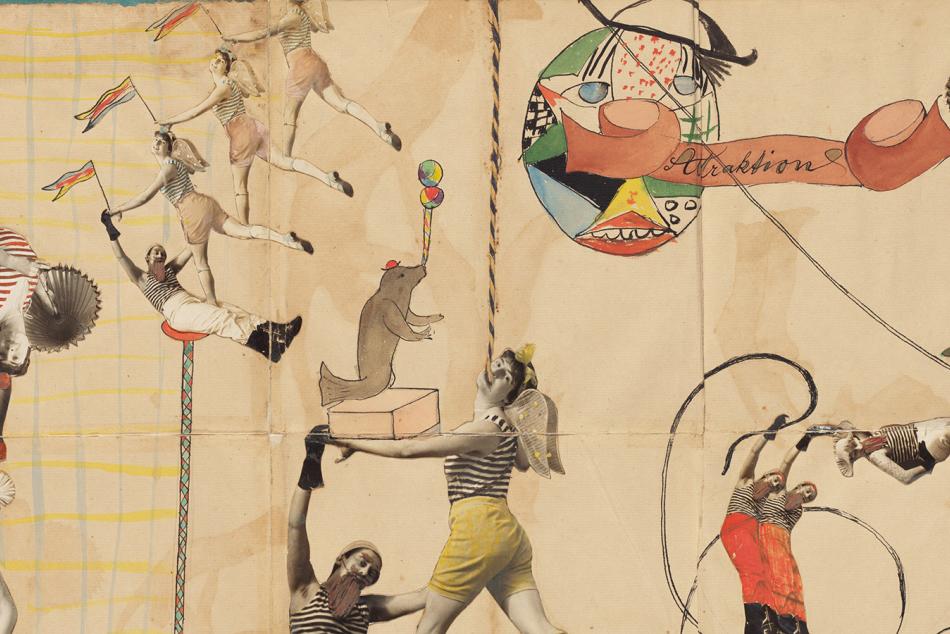

Article: Queer Artists Grete Stern and Ellen Auerbach: ringl + pit

How the duo’s book documents their artistic collaboration and romantic relationship through beautiful, witty, and sometimes irreverent mixed media art.