The Real Lives of People in Dorothea Lange's Portraits

You may recognize some of these iconic photographs—but do you know the stories of the people in them?

Dorothea Lange was a talented portrait photographer—and those works are the subject of our exhibition Dorothea Lange: Seeing People. But it wasn’t just her technical abilities that made her images powerful.

Lange connected with her subjects. She spoke with them about their lives and challenges. She learned about their concern for their children, frustration with the government, and fears for their safety. She often took detailed notes and turned quotes into captions for her photographs. But in some instances (including for her famous Migrant Mother), Lange left no record. It was only decades later that we learned about the lives and experiences of those subjects.

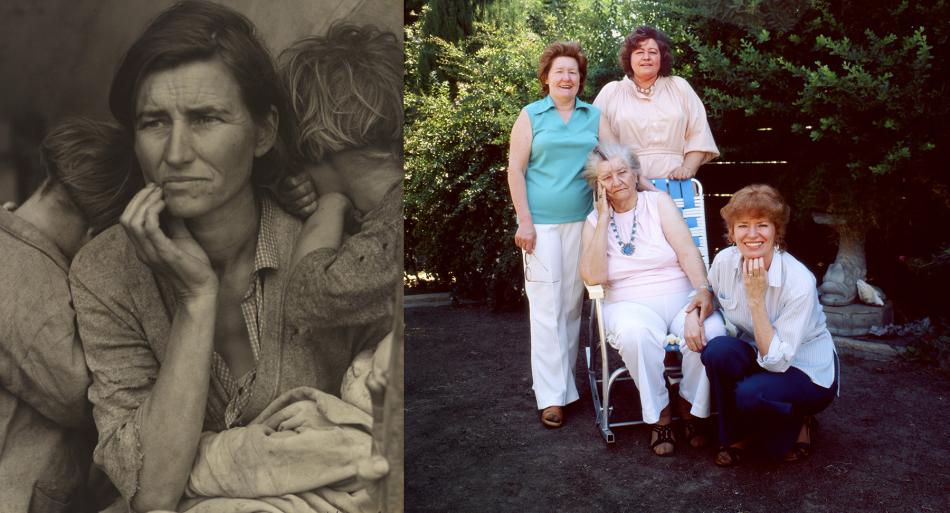

Florence Owens Thompson

Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother) captures the worry, need, and insecurity of everyday Americans during the Great Depression. It is one of the most recognizable American photographs. And it almost wasn’t taken.

In spring 1935, Lange was driving home from a long trip photographing migrant worker camps when she passed a sign pointing toward a pea pickers camp. Lange had already taken many photographs of pea pickers. She tried to convince herself that she didn’t need any more. But about 20 miles later, she turned around.

We don’t know exactly what happened when Lange doubled back—this time, she didn’t take notes. And she didn’t ask many questions. Lange assumed that she had come upon a mother and her three children, there among the waves of workers coming to pick peas, California’s cash crop.

But that wasn’t true. Florence Owen Thompson was traveling with her family from elsewhere in California. The family had set up a camp on the side of the road while her husband and son went into town to resolve some car troubles. When they returned, she mentioned a photographer had taken some photos. Thompson never expected one of those photographs to immortalize her as the “Migrant Mother.” Decades later she wrote a letter to the editor of her local paper expressing irritation with her likeness being misused. In a later interview, Thompson expressed regret at ever allowing Lange to take the photo saying, "I wish she hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. [Lange] didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did."

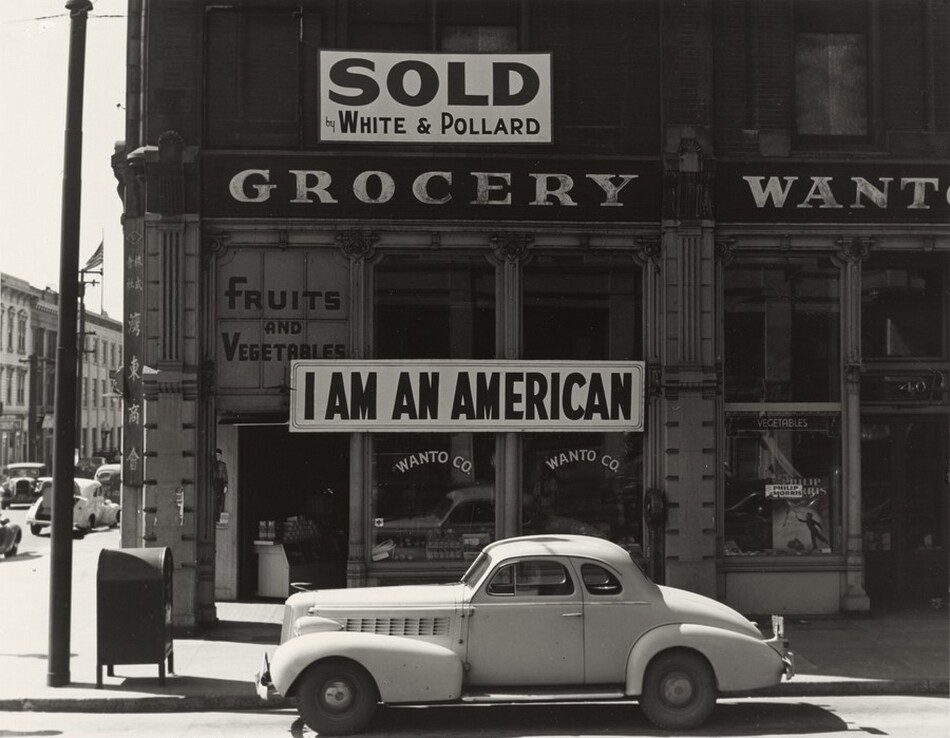

Tatsuro Masuda

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942. The order forced the unjust incarceration of more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent (the majority of whom were American citizens). The War Relocation Authority hired Lange to document this process. Lange was horrified by what she witnessed. She chronicled her subjects in a sympathetic light, so much so that her photographs were censored during the war.

Lange began by photographing Japanese Americans as they prepared to abandon their homes. She took this picture of a grocery store on a street corner in Oakland, California, in March 1942, a month after the executive order was issued.

Tatsuro Masuda ran the Wanto Company store (look for its name on the windows), opened by his father in 1900. Fearful of growing anti-Japanese sentiments, Masuda paid for the “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign to be installed the day after Pearl Harbor. By the time Lange took the photograph, Masuda decided to close the store. Japanese Americans were forced to sell or relinquish any property they couldn’t carry with them. He moved to Fresno with his new wife, Hatsue Kuge. In August the couple (now expecting their first child) were incarcerated at Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona. Their second child was born at Gila, as well. They weren’t released until October 1944.

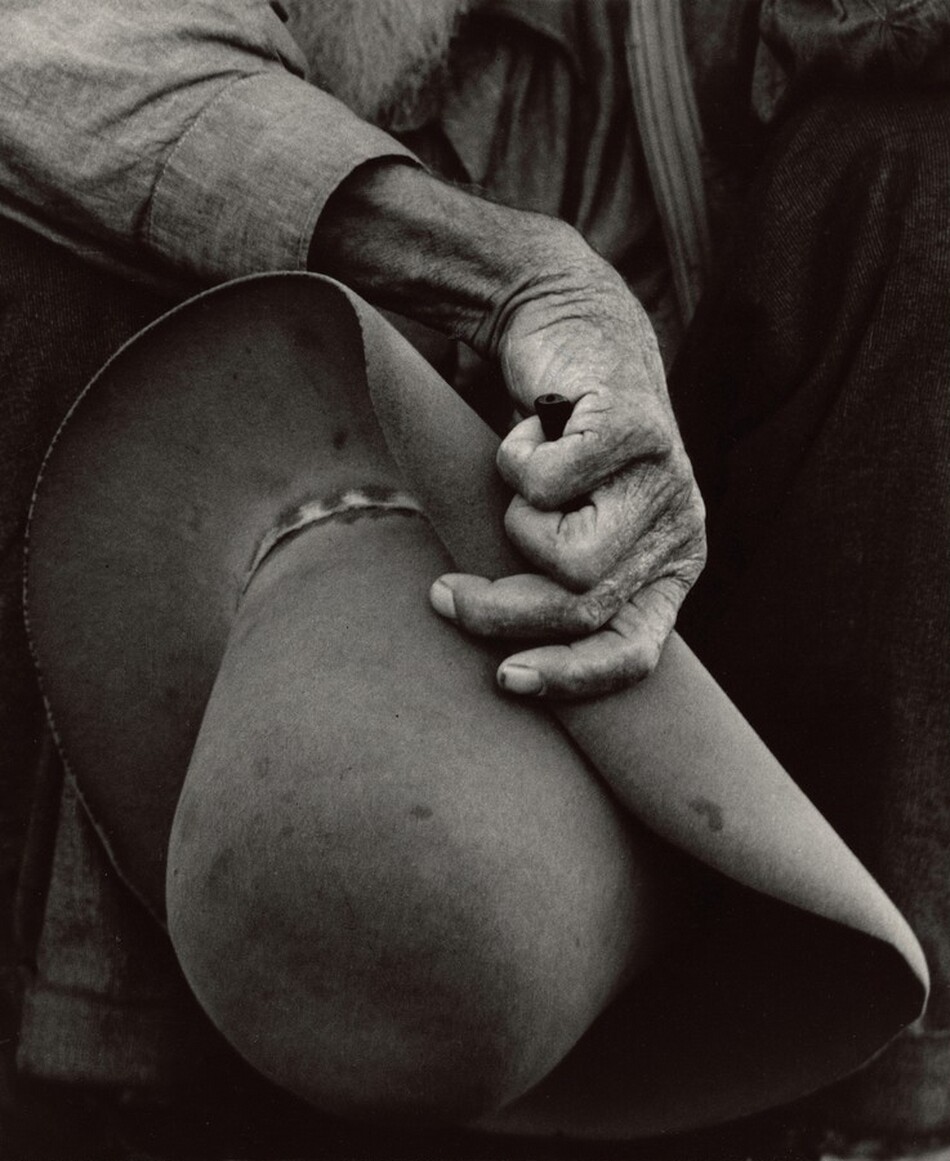

James Abner Turpen

From 1936 to 1939, Lange worked for the Resettlement Administration (which later became the Farm Security Administration). In Texas she documented the impacts of mechanization on farmers. In the town of Goodlett she met James Abner Turpen, a 70-year-old tenant farmer who was about to be “tractored out” of his farm. Realizing that agricultural machines like tractors could replace many farmers, landowners would evict their tenant farmers.

Turpen’s sons had already been tractored out. In her caption, Lange recorded his distress. “What are my boys going to do?” he asked. He believed the government was partly to blame. “They're not any up there in Congress but what are big landowners and they're going to see that the program is in their interest."

Lange cropped one image to focus on Turpen’s weathered hand grasping his hat. The photograph is titled On the Plains a Hat Is More Than a Covering. But curator Philip Brookman inspected the image closely and compared it with others to confirm that Turpen is the subject.

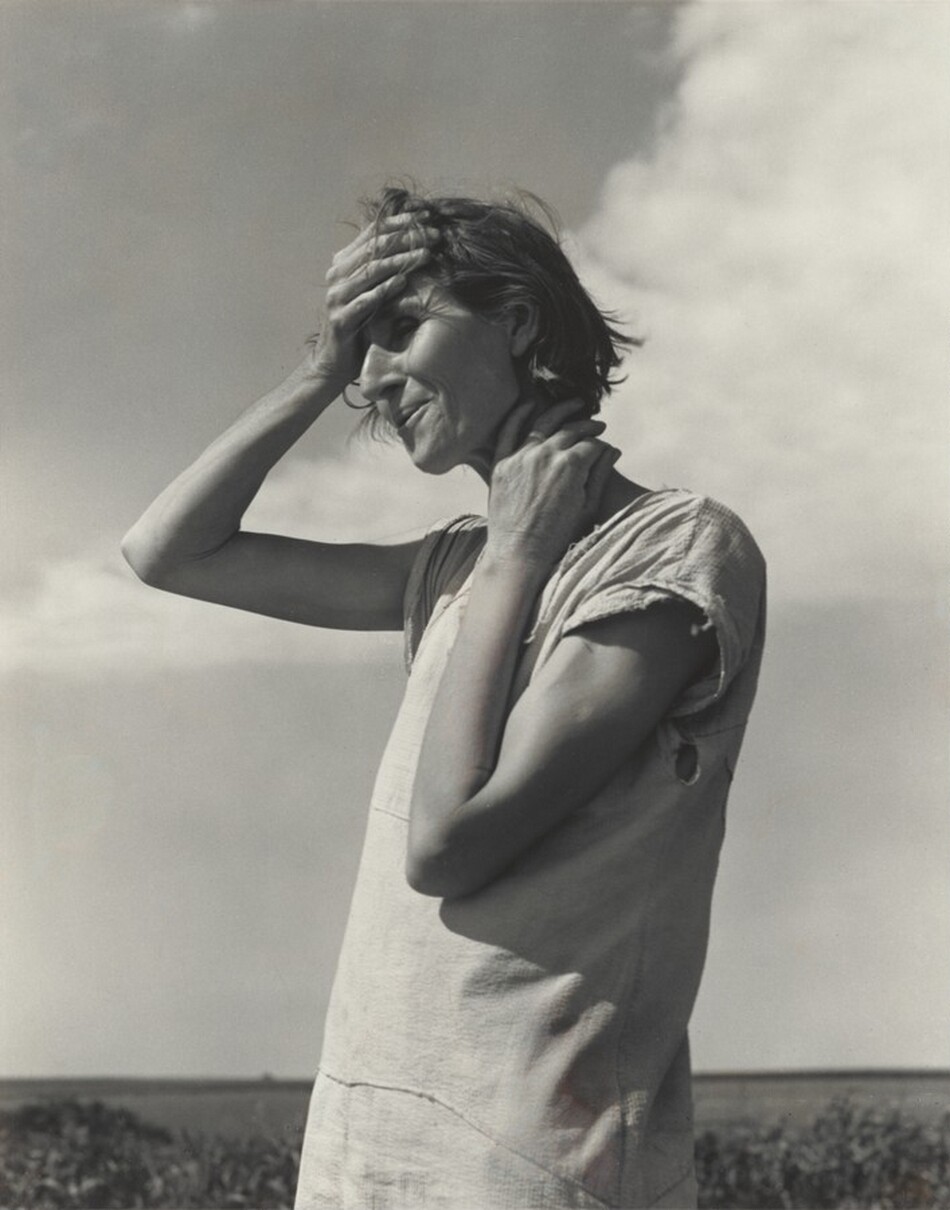

Nettie Featherston

Lange met Nettie Featherston while working on that same FSA project. Like Turpen, Featherston’s family had been forced off their farm in Oklahoma. On their way to California to find work, they ran out of money and found themselves stranded in Childress, Texas.

The Featherstons sold their car for money to buy food. That left them with no way out of the dry and dusty landscape we seen behind Featherston. She looks desperate and distraught. “This county’s a hard county. They won’t help bury you here. If you die, you’re dead, that’s all,” she told Lange.

Decades later photographer and author Bill Ganzel tracked down Featherston. Then in her 80s, she still remembered how difficult that time had been. “Your kids would cry for something to eat, and you couldn’t give it. We cooked with black-eyed peas until I never wanted to ever see another black-eyed pea.”

You may also like

Article: Who Is Dorothea Lange? 6 Things to Know

Learn how the documentary photographer got her start and why she dedicated her life to the medium.

Article: Outside the Frame: How Dorothea Lange Created Her Iconic Photographs

Learn about the documentary photographer’s techniques by tracing the process of creating some of her compelling images.