Going through Hell? See Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” in Art

Italian poet Dante Alighieri wrote The Divine Comedy (La Commedia) more than 700 years ago. It describes one man’s journey through the afterlife, telling a timeless story about love, faith, and justice.

Dante has inspired everyone from French sculptor Auguste Rodin to British draftsman William Blake. You can see how different artists have imagined the story below and in our exhibition, Going through Hell: The Divine Dante, on view from April 9 to July 16.

Dante’s epic poem may be called The Divine Comedy, but don’t expect to laugh—commedia used to mean something that begins in sadness but ends well. This is a dark story with a happy ending.

The narrator and main character is Dante himself. Virgil, the ancient Roman poet, guides this journey, which is split into three parts: Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise.

Hell

Dante first describes traveling through the nine circles of Hell (Inferno). Sinners are assigned to the circles according to their sins: the least offensive are in the First, limbo, and the worst are in in the Ninth, treachery.

The Second Circle of Hell is lust. In the fifth chapter, or canto, Dante meets Paolo and Francesca. Both were married to other people, but they fell in love with each other and kissed while reading a book together. Francesca’s husband murdered the couple, and they landed in the Second Circle together.

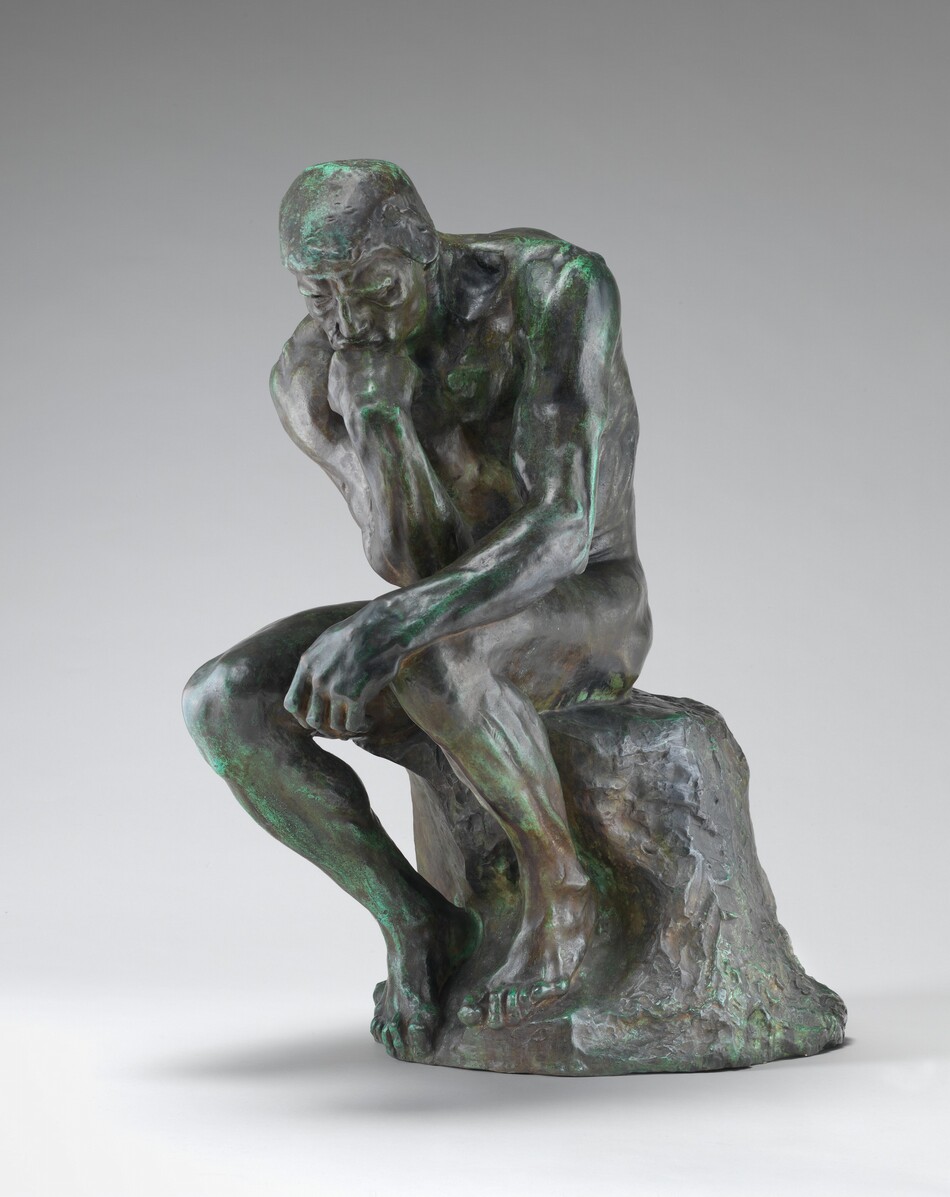

French sculptor Auguste Rodin’s bronze work shows that romantic, but damning, kiss. Rodin designed this sculpture for his Gates of Hell, two bronze doors inspired by Dante’s Inferno. His iconic sculpture, The Thinker, also came from this work. The man resting his chin on his hand represents Dante.

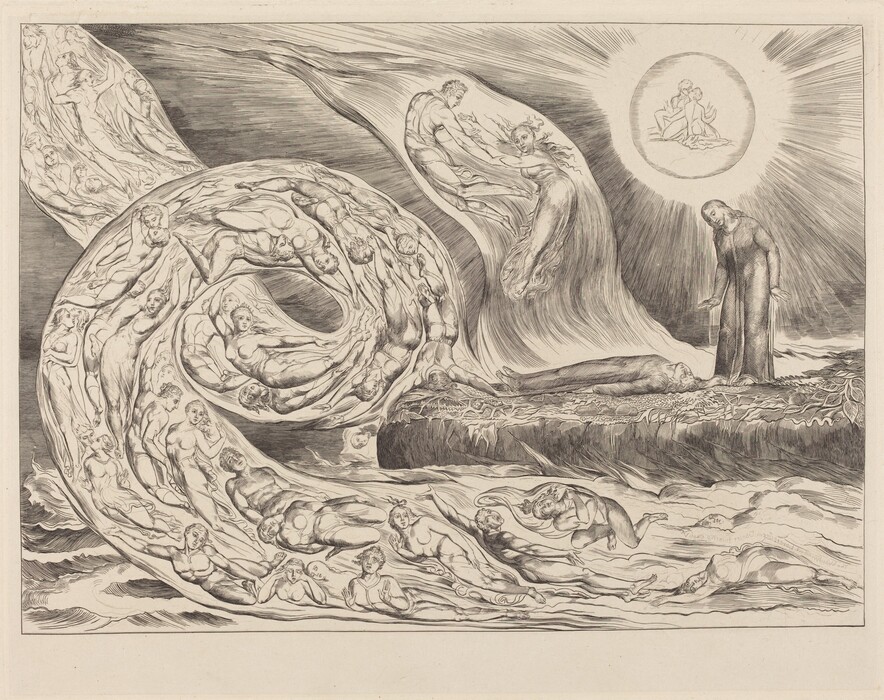

In this engraving, British poet and artist William Blake shows Paolo and Francesca being swept away in a whirlwind of irresistible desire. Blake made 100 drawings of the story while he was sick in bed.

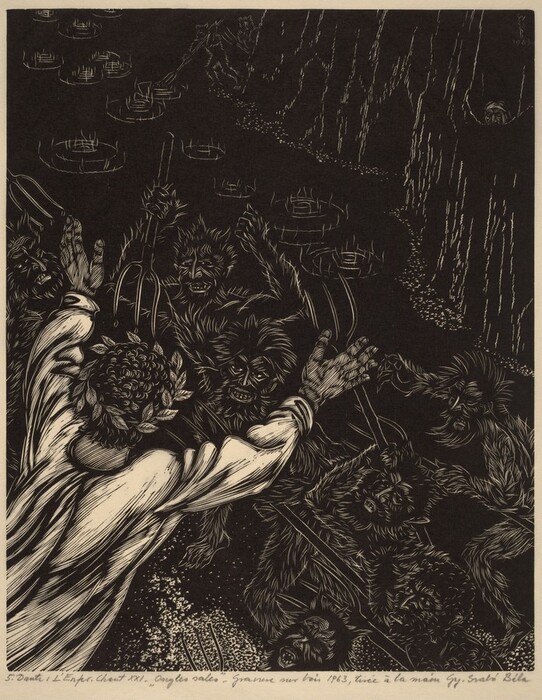

With a wood engraving by Romanian artist Gy Szabó Béla, we skip ahead to the Eighth Circle of Hell. Reserved for those who have committed fraud, the Eighth Circle is said to be “marvelously dark.”

Szabó’s print shows Virgil from behind, but we can recognize him from the laurel wreath on his head. He is overlooking a pitch-black pit as hairy demons holding pitchforks rise toward him. In the Comedy, these demons are supposed to keep corrupt politicians under the boiling lake of pitch (or tar) that we can see bubbling behind them.

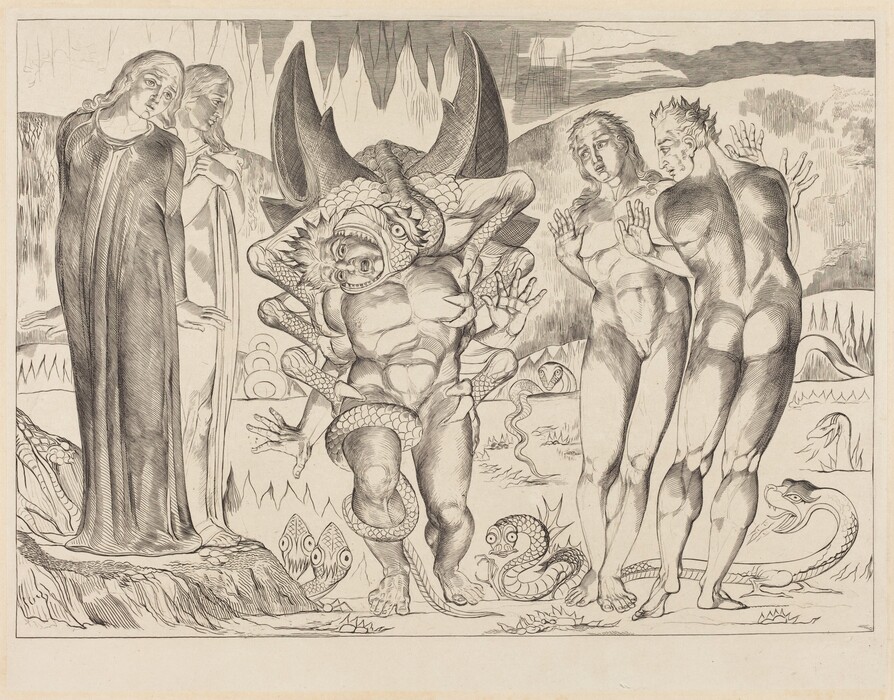

Thieves are also sent to the Eighth Circle, where they take turns becoming snakes to steal one another’s identities. Both William Blake and early 20th-century American artist Rico Lebrun show these sinners tormented by snakes. In Blake’s engraving, “a serpent with six feet” sits on the shoulders of a sinner. The creature has the man’s head in its mouth and its tail wrapped around his leg. Other snakes slither about—one is about to sink its fangs into the figure on the far right.

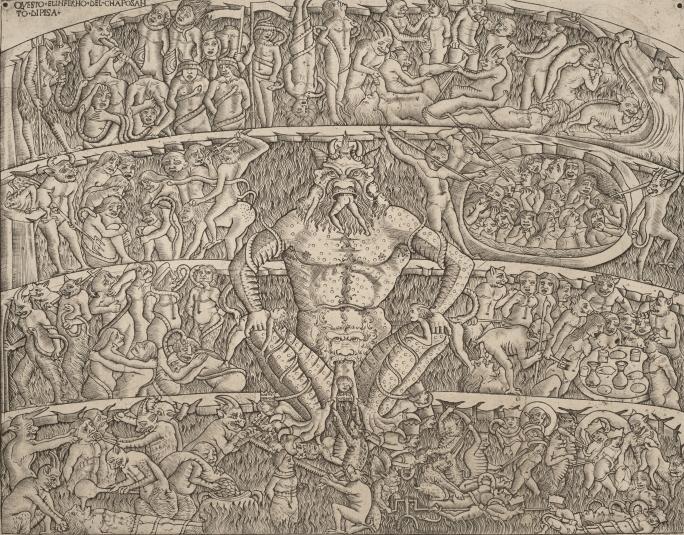

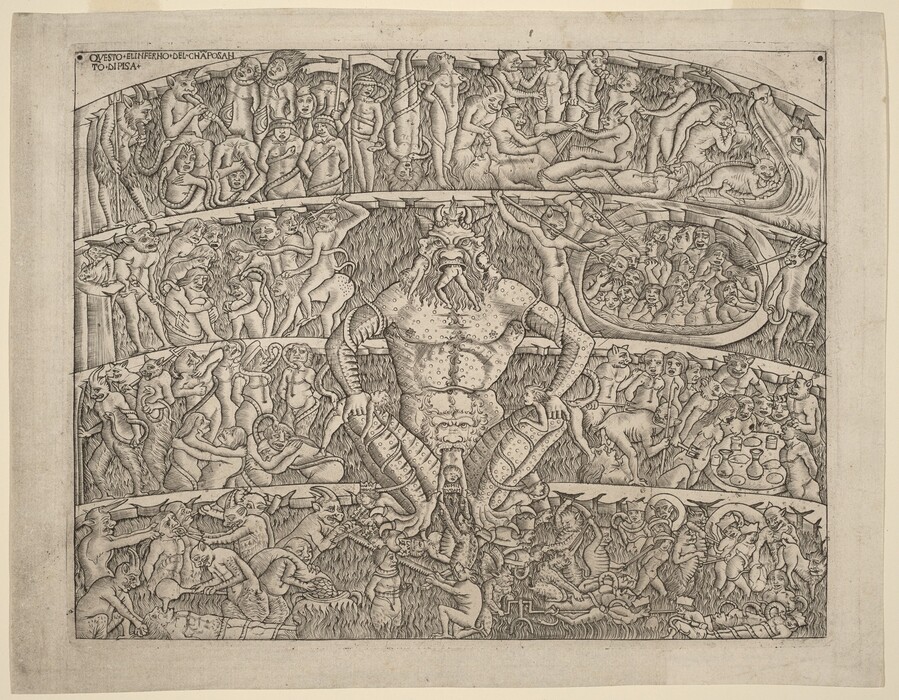

Eventually, Dante and Virgil meet Satan, who has bat-like wings and three faces. He feasts on a sinner in each mouth. This engraving was modeled after a fresco (a mural painted on wet plaster) by Buonamico Buffalmacco in the Campo Santo cemetery in Pisa, Italy. It brings to life the darkest level of Hell, complete with flames rising from the bottom. Take a closer look, but be warned . . . it’s gory!

Purgatory

After Hell, Dante reaches Purgatory—a mountain where people prepare themselves for heaven, or paradise. This late 15th-century bronze coin and 16th-century Allegorical Portrait of Dante show the poet with that mountain.

Both were made in Florence, where Dante was born. He was exiled from his hometown after being accused of corruption and financial wrongdoing. In the portrait, he looks back at Purgatory, holding a book open to a poem describing his longing to return to Florence. Here, the desires of Dante the poet overlap with those of Dante the character.

Paradise

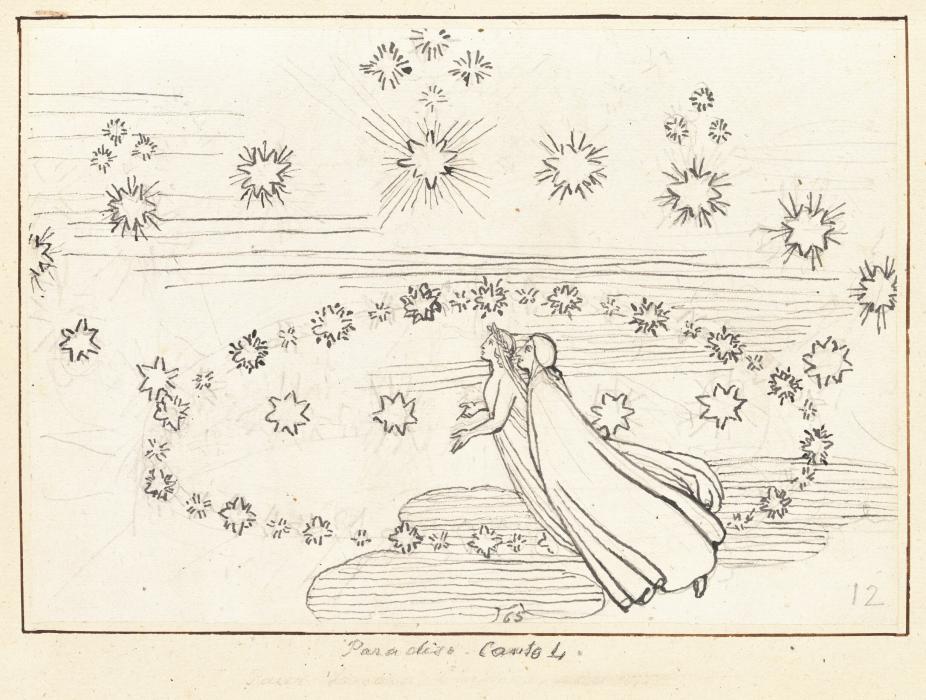

Finally, Dante arrives in Paradise. There, he is guided by Beatrice, a character inspired by the real love of Dante’s life and the muse for many of his poems. This pen and ink drawing comes from a suite that British artist John Flaxman published in 1807 in a popular illustrated edition of the Comedy. With simple lines, Flaxman shows Beatrice guiding Dante through the nine spheres of Heaven. They float among the planets and stars.

John Flaxman, Album of Drawings for Dante's "Divine Comedy", c. 1793, bound volume with 78 drawings in pen and ink and graphite, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.3734

This print is based on a fresco by Italian Renaissance painter Domenico di Michelino in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. It shows Dante with all three realms—Hell on the left, Purgatory behind him, and Paradise above with the curved lines and stars. On the right, we can recognize Florence by the iconic dome and tower of the cathedral. Dante stands in the center of the image, larger than life, holding his greatest work.

After Domenico di Michelino, Dante as the poet of the Divine Comedy, 1417-1491, heliogravure, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

You may also like

Article: A Poem of Exile on Dante Day

A look at the writer, poet, and father of the modern Italian language.

Article: Poet Ilya Kaminsky Responds to a Sculpture by Alberto Giacometti

The author of "Deaf Republic" imagines a convening with the "long-legged statue."