Race in America

Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, or Hendrick Tejonihokarawa, a Mohawk chief, was one of four Native men who traveled to Britain in 1710 on a diplomatic mission. While there, the men became celebrities and their portraits were painted by Dutch artist John Verelst for Queen Anne. Their portraits reveal contradictions: the men are depicted as leaders and allies, yet at the time Natives were often portrayed in European cultures as “savages” or “heathens.”

Tejonihokarawa appears here in an American landscape in British dress. European viewers would have connected his buckled shoes to the lofty title invented for him: Emperor of Six Nations. He holds a wampum belt—a symbol of alliance—decorated with Christian crosses. Next to him stands a wolf, symbolizing his clan affiliation within his tribe.

There is evidence that Tejonihokarawa willingly participated in the diplomatic mission. He was pro-British and wanted to position the Haudenosaunee (a confederacy of five Native nations) as a powerful ally who could push back against the French and their Catholic missionaries.

As you look at Tejonihokarawa’s portrait, what stands out to you? What choice or agency do you think he might have had in the creation of his portrait?

John Simon after John Verelst,

When you think of George Washington, what comes to mind?

This group portrait, titled The Washington Family, shows Washington and his wife Martha with their two grandchildren and an enslaved valet. Washington is dressed in his military uniform, leaning on his adopted grandson, whose hand rests on an astrolabe, a tool referring to Washington’s experience as a land surveyor. The setting is intended to represent Mount Vernon, their plantation home. In the center of the picture is a map showing Washington, DC, the future capital of the United States.

George and Martha Washington enslaved 317 people at Mount Vernon. The enslaved valet in this painting may be intended to represent one of at least two men who worked in this role:

William Lee was Washington’s valet and personal assistant for over 20 years, including through the Revolutionary War. He was known as an expert horseman. Lee was the only person freed by Washington at the time of his death. Lee remained at Mount Vernon after being freed and is buried there.

Christopher Sheels became Washington’s valet after William Lee became permanently disabled. He and his wife attempted to run away, but a note making the arrangements was discovered. Sheels stood by Washington’s bedside for hours as the president died. He was not freed at Washington’s death; instead, he was probably inherited by Washington’s grandson, shown here. There is no further record of him.

Edward Savage was a self-taught European American artist born in Massachusetts. Why do you think he included an enslaved valet in his painting The Washington Family?

Edward Savage,

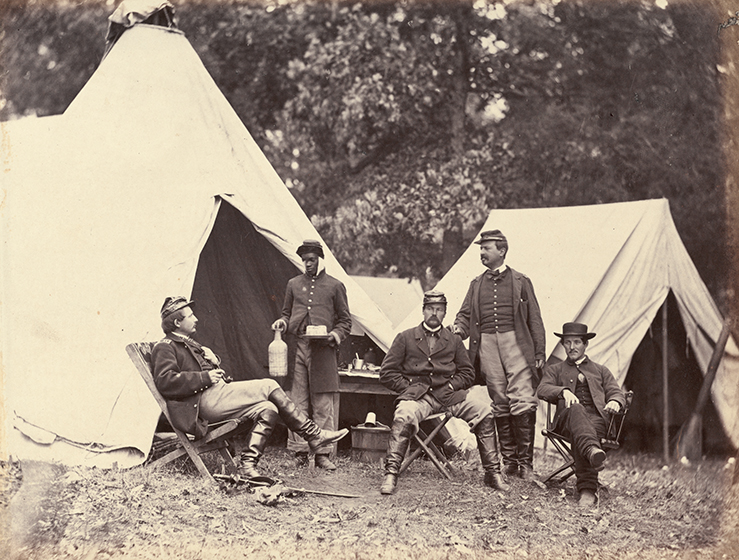

This staged Civil War photograph makes a joke at the expense of an African American man referred to as John Henry. The title—What Do I Want, John Henry?—is a musing the captain, at left, often voiced to Henry. Henry offers a jug of liquor, described by Scottish-born photographer Alexander Gardner “as the only appropriate prescription for the occasion that his untutored nature could suggest.”

Henry had escaped his Southern slaveholders and offered his services to the Union army, which led him to be labeled as “contraband.” Contraband individuals were not fully freed, but they were eventually paid for their services by the army—though sometimes inconsistently and unfairly. This photograph was made in 1862, a year before African Americans were recruited by the Union army.

Look at the positions, poses, and expressions of the men in this photograph. Who has power, and how can you tell? What does this make you think about the process of transitioning from enslavement to freedom?

Alexander Gardner,

Compare these two fighters. Who do you think will win the fight? How is the audience responding?

When George Bellows made this painting, public boxing was illegal in New York. To get around the law, promoters advertised fights for “members only”: individuals who paid fees to join a “club” and watch fights. The work’s title refers to this practice, but also suggests that, outside the ring, African Americans and European Americans were not members of the same “club.” One scholar has argued that Bellows—a European American artist from Ohio—made the painting to help white audiences process their racial anxiety around Jack Johnson, an African American boxer who won the world heavyweight title in 1908. Johnson’s victory, like Bellows’s painting, made clear that white fighters were not superior, calling into question the racial hierarchy in place across the United States.

Where and how do you see racial hierarchies still in play in sports today?

George Bellows,

The mammy figure is a racist caricature that emerged during slavery and proliferated during the Jim Crow era, from Reconstruction through the 1960s. Mammies are stereotypes of Black women who served in domestic roles in white households. They are often depicted in literature, movies, and commercial ads as cooks or caregivers who are overweight, good-natured, and deferential. Additionally, as one scholar points out, they are portrayed as asexual. This depiction of Black domestic servants helped white supremacists deny the reality that male slaveholders sexually assaulted enslaved women.

This work is a watercolor rendering of a bank in the form of a mammy. It was made by artist Robert Clark, likely European American, for the Index of American Design, a Depression era federal relief project. One of the goals of this project was to “record material of historical significance which has not heretofore been studied and which, for one reason or another, stands in danger of being lost.”

What can we learn from studying objects like this?

Robert Clark,

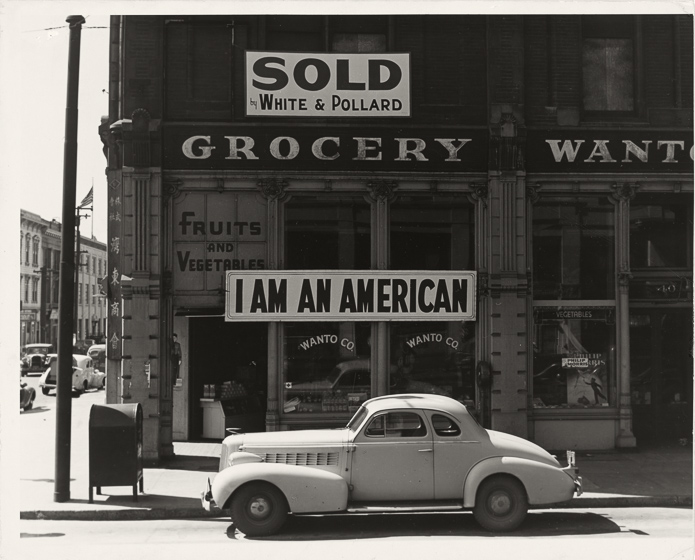

The US government hired Dorothea Lange—a European American artist widely known for her photos of Depression era migrants—to photograph the process of incarcerating Japanese Americans after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. The government hoped to use the images to promote the internment program. But instead, Lange’s photographs were impounded until the end of World War II, then placed in the National Archives. What stage of the internment process do you think this photograph depicts?

More than 100,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned in camps, and more than half of them were US citizens. In the 1980s, a Congressional commission determined that racism was the cause of incarceration, and in 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed legislation apologizing on behalf of the US government. The government authorized $20,000 payments to each survivor.

What might have compelled the grocery store owner to put up this sign? Have you ever had your “Americanness” questioned?

Dorothea Lange,

A Black ticket taker is the focal point of this painting. African American artist James Amos Porter created this depiction of Griffith Stadium, a multipurpose arena in Washington, DC, in the early 1940s.

The people shown here were likely attending a baseball game. Griffith Stadium was home to the Washington Senators from 1911 to 1960. Like many places in Washington, DC, the stadium was not officially segregated, but Black fans followed an unspoken policy to sit in a particular section of the stands.

Porter taught art and art history at his alma mater, Howard University, in Washington, DC, for more than 40 years. He published the first major history of African American art in 1943. Why do you think Porter placed the ticket taker at the center of his painting?

James Amos Porter,

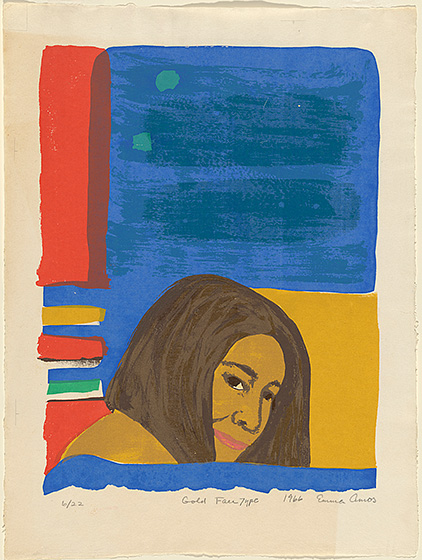

How would you describe the expression on this woman’s face?

Emma Amos made this self-portrait in 1966, the same year she received her master’s degree. She had been living and working in New York since 1960, and in 1964 became the youngest and sole woman member of Spiral, a collective of Black artists. Spiral formed in response to the momentous 1963 March on Washington to consider the role of African American artists in the civil rights movement.

Amos was a painter, printmaker, and weaver from Atlanta whose finished works incorporate multiple techniques and ideas. “The work,” wrote Amos, “reflects my investigations into the otherness often seen by white male artists, along with the notion of desire, the dark body versus the white body, racism, and my wish to provoke more thoughtful ways of thinking and seeing.”

What surprises you about this self-portrait? How do you think Amos was pushing against the idea of “otherness”?

Emma Amos,

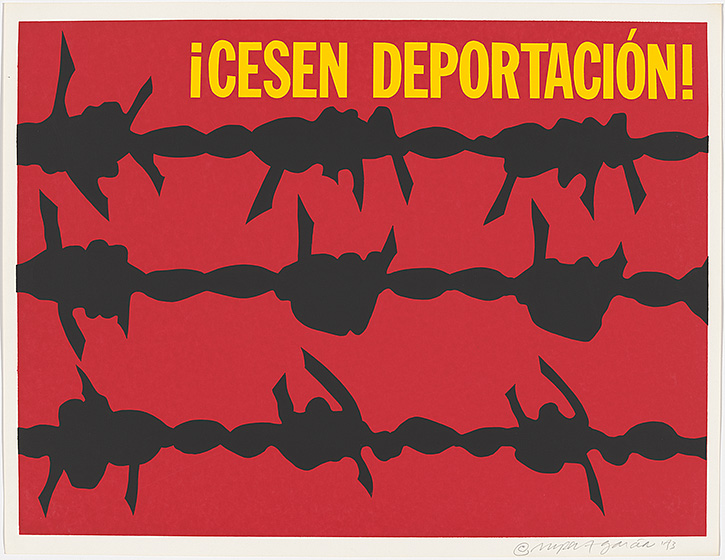

What message does this image send to you?

Rupert García is a Mexican American artist from California whose work addresses civil rights, racism, and specific injustices against Latin American communities. He created this poster—“Cease Deportation!” in English—in the early 1970s to protest deportations of undocumented Mexican immigrants. Legislative efforts to criminalize immigrants followed on the heels of the bracero program, which brought millions of Mexican guest workers to the United States between 1946 and 1964.

Many Chicano artists—those of Mexican descent—use barbed wire in their works. What does barbed wire make you think of? How does it function here as a symbol?

Rupert García,

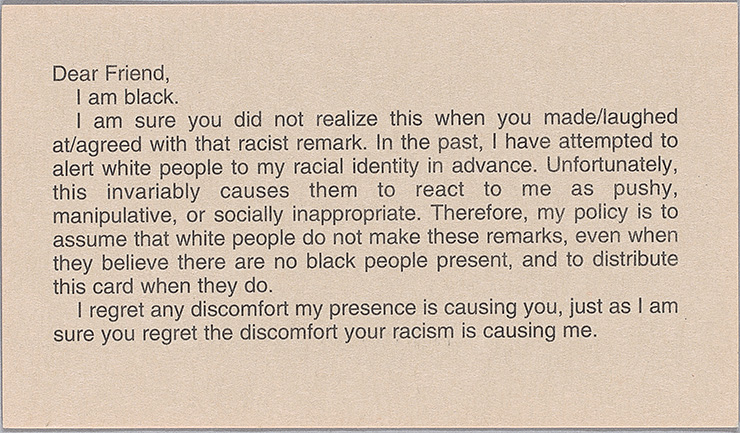

This is one of two different calling cards that Adrian Piper made in the late 1980s. She gave this version to people who made racist remarks in front of her.

Now based in Berlin, Germany, Piper is an artist and philosopher who changed her racial designation to “gray” in a 2012 performance piece. She has identified as African American and multiracial in the past. Her participatory and performative works challenge assumptions about social structures. They usually ask individuals to reflect or act in some way.

Why do you think Piper used this format—a handout the size of a business card—to create this work? Read the text. What feelings or reactions do you think the exchange and card elicited in its recipients?

Adrian Piper,

Each panel in Byron Kim’s Synecdoche represents the skin tone of an individual: a friend, family member, colleague, neighbor, or stranger. The work functions both as a group portrait and as a collection of simply painted panels in a minimal range of colors. Kim, who is Korean American, began the work in 1991 and continues to add panels (organized alphabetically by first name) from time to time. The word “synecdoche” is defined as a figure of speech in which a part of something stands in for the whole.

Many viewers understand this work of art to be a political statement on race and the construction of race in the United States. What do you think this work says about race and identity? What can you learn about the individual sitters for this work of art? How is Synecdoche similar to or different from a traditional portrait?

Byron Kim,

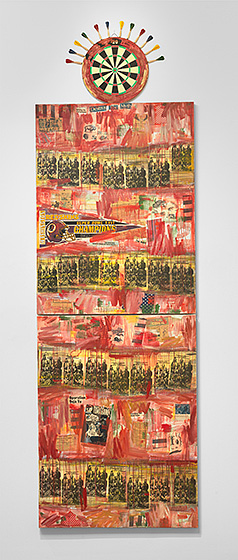

I See Red: Target is part of a series by artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (enrolled Salish, member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, Montana). She began the series in 1992 upon the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s landing in the Americas. The work incorporates stereotypes, racist tropes, and imagery that relates to the appropriation of Native Americans. Said Quick-to-See Smith, “I reference Indians being the Target of the corporate world of mascots and corporate goods.”

Look closely at this work and you will see that it is a collage. Quick-to-See Smith adds images and headlines from magazines and newspapers, including the Char-Koosta News, the Flathead Reservation newspaper published where she grew up. The dartboard serves as a target, with darts placed around it like feathers in a headdress. A pennant at top left celebrates the Washington football team, winners of the 1992 Super Bowl over the Buffalo Bills. Quick-to-See Smith refers to the Bills’ mascot, the bison, at upper right; the appearance of a racial slur for Native Americans connects to the work’s title and its dominant color.

Where else in your life do you see appropriation of Native American imagery? Consider other products, symbols, and visual media.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,

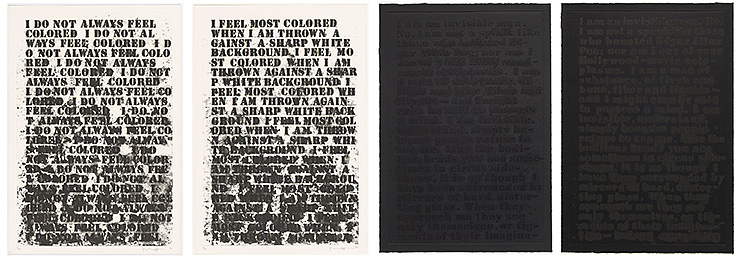

What colors and textures do you notice in these four prints? How would you describe their appearance?

African American artist Glenn Ligon based these works on two texts by African American writers. The black-on-white prints feature lines from Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels To Be Colored Me,” while the two black-on-black works feature lines from Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man. The quotations speak to the experience of being Black in a country that privileges whiteness, as do Ligon’s use and treatment of them: notice how lines repeat and punctuation is removed.

What effect do you think repetition has in these works? Why might Ligon have purposely obscured the text or made it difficult to read? Try reading the prints line by line and see what you notice.

Glenn Ligon,

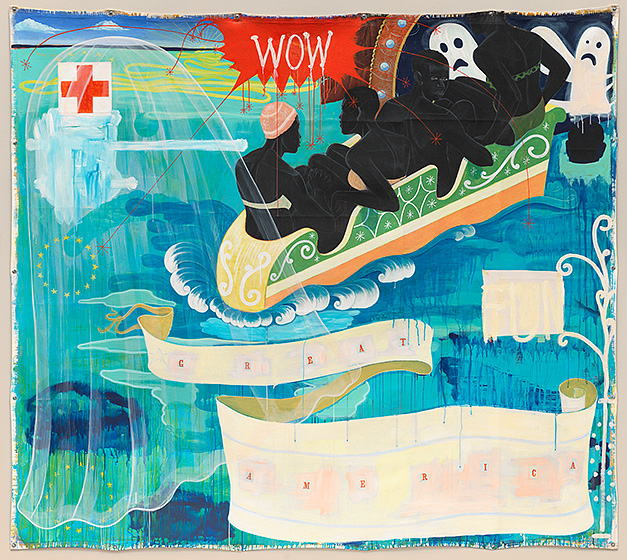

African American artist Kerry James Marshall has talked about the Middle Passage—the journeys of slave ships across the Atlantic Ocean—as the “zero point” of African American history. Tracing his lineage back to something so violent, traumatic, and fundamentally unknowable led Marshall to create works that displace violence with other imagery. In the case of Great America, Marshall uses elements from an amusement park.

From the 1400s to the 1800s, European slavers transported millions of Africans across the Atlantic Ocean for colonial destinations in South and North America. At least 15 percent of those enslaved died during the horrific journeys. People were packed into ships like cargo, and food and water were scarce. Disease, starvation, and depression were common, and many resisted through suicide and self-starvation. Acts of rebellion and uprising were also attempted.

Look closely at the figures Marshall depicts here. How would you describe their poses and expressions? What connections does Marshall make to those who experienced the Middle Passage?

The transatlantic slave trade was outlawed in 1807, but slavery persisted in the United States, instigating a civil war between Northern and Southern states in 1861. Slavery was abolished when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in 1865, though full voting rights were not accorded to African Americans and other people of color until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Kerry James Marshall,

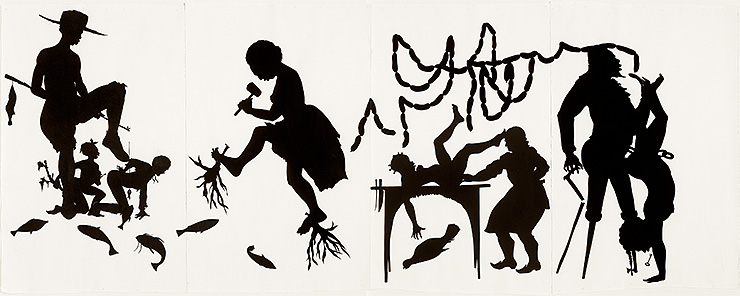

“Walker operates on the premise that when you make history truly visible, both your own and that of your people or nation, there exists a challenge to show all of it, the unholy mix, the conscious knowledge and the subconscious reaction, the traumatic history and the trauma it has created, the unprocessed and the unprocessable.” —Zadie Smith

The work of African American artist Kara Walker is both praised and contested by artists and critics. Her work routinely pictures violence, sadism, and racist and sexist stereotypes coexisting with fantasy-like narratives. Cut-paper silhouettes both hide and reveal individuals and their actions. The abbreviation “Inc.” in this work’s title refers to the institutionalization of racism and the implicit cultural approval of such degrading images. What might “roots” and “links” refer to?

How do you feel about Kara Walker’s work?

Kara Walker,

All the Boys is part of a series by African American artist Carrie Mae Weems about the systematic violence sustained by people of color, especially African Americans, at the hands of US authorities. Weems made these works in response to the killings of Black men and boys, including Laquan McDonald and Alton Sterling, who were both killed during altercations with police officers.

Here, Weems shows a man facing forward and in profile, referencing police mug shots. The man wears a hoodie, referring to criminal stereotypes associated with Black men, but his identity is obscured. The photograph is out of focus and the print is tinted blue. What do you think Weems might be communicating through these artistic choices?

Carrie Mae Weems,