Great Depression

This image is of a breadline in Cuba, showing us the effect of the Great Depression on other nations. People line up against a fence, where a sign reads: “Cocina gratuita de Periodico, Departo de Raciones” (Temporary Free Kitchen, Ration Distribution).

Walker Evans went to Cuba in 1933, but not to document the effects of the Depression. He was on assignment to take photographs for a book entitled The Crime of Cuba. The book was a critique of the regime of President Gerardo Machado y Morales, in office from 1925 to 1933. As the Depression was felt in Cuba, Machado’s regime became increasingly repressive, which fostered civil unrest. He was overthrown with assistance from the United States shortly after The Crime of Cuba was published. Machado was succeeded by Fulgencio Batista who was, in turn, overthrown by Fidel Castro in 1956.

Walker Evans, The Breadline, 1933, gelatin silver print, Gift of Katherine L. Meier and Edward J. Lenkin, 1991.173.1

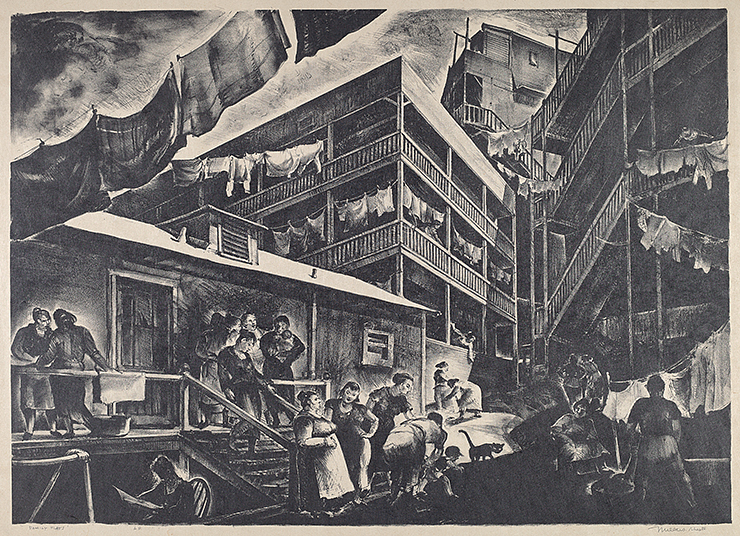

“Family flats” were houses and buildings divided by a landlord into small apartments, often overcrowded and in poor condition, and were also known as tenements. Such housing was frequently the only option for poor families. The place shown here is Millard Sheets’s native Los Angeles, in a neighborhood that no longer exists called Bunker Hill. You can get a sense of the pitched topography as the buildings at the top of the image rise quite high above the figures at the very bottom of the frame. It is laundry day and groups of women chat, do their wash using buckets (at right), and hang clothes on the swinging lines that crisscross the picture. Try to count the number of clotheslines and then the number of other diagonal forms. Name each type of diagonal you see (e.g., roofline, railing, stair). How do the diagonals create a sense of activity and movement? Imagine if the lines were all perpendicular or parallel. How would the scene be different? Try to draw a sketch of the scene replacing the diagonals with perpendicular or parallel lines. See the Pinterest board for a painting of this same scene that Sheets painted in 1934, upon which he based this print.

Millard Sheets, Family Flats, 1935, lithograph in black on heavy Japanese paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.4385

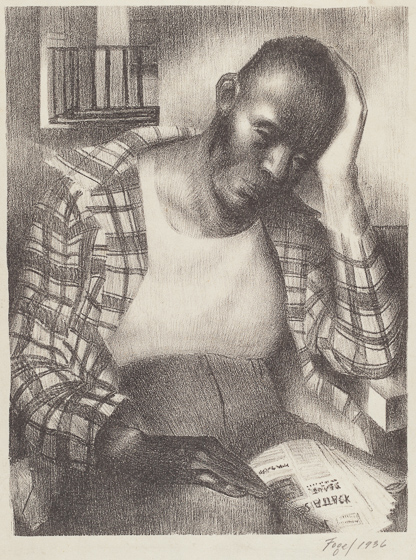

This empathic and realistic portrait of a man burdened by hard times is a compelling one. The word “attack” can be made out on the newspaper on the man’s lap. Note that the word is written backward. This is because the work is a print, the orientation of which is reversed when the paper is applied to the lithographic stone. What attack might the newspaper be announcing given the man’s attitude and the date of the image? How did events of the day both negatively and positively affect life for ordinary Americans?

The artist, Seymour Fogel, worked as an apprentice to Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in New York. Rivera’s art was in high demand during the 1930s and he traveled the United States completing mural commissions. Fogel went on to paint approximately 20 of his own public murals for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project and with the Department of the Treasury. See the resources section of this module to help you locate WPA-era murals and public works in your own community.

Seymour Fogel, Untitled (Pensive Black Man), 1936, lithograph, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.1807

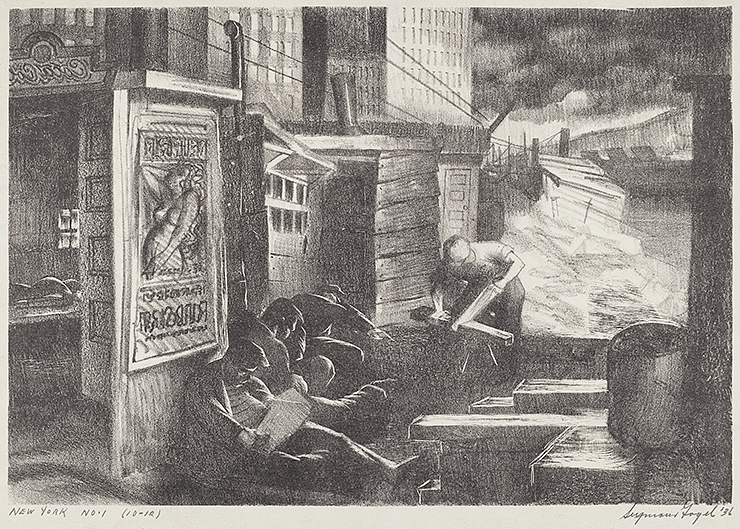

While one man works, sawing wood at the center of the image, others sit on the ground around him, dozing or reading a newspaper perhaps. The time may be night, with illumination coming from streetlights beyond where the men are gathered. A poster with an alluring female figure is featured, perhaps advertising a burlesque show, and suggesting moral temptations to men not gainfully occupied. Although the setting is ambiguous, the man may be sawing wood to create a shanty or shelter of some sort, as the slanted panels just behind him suggest. During the Depression, people made homeless by the crisis often built such improvised structures. Groupings of such dwellings were dubbed “Hoovervilles” in critique of President Herbert Hoover (in office from 1929 to 1933), who was unable to enact programs to effectively assist people plunged into poverty by the Depression. What parts of the scene tell you that this group of people may have fallen on hard times? Please see the Pinterest board for additional related images.

Seymour Fogel, New York No. 1, 1936, lithograph, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.1805

Walker Evans had a keen eye for the telling detail. He photographed this weathered window featuring a poster for presidential candidate Herbert Hoover. Hoover ran for and won the presidency in 1928, elected on the strength of his successful work to alleviate hunger in Europe after World War I. If you look closely, you can make out the “-er” of “Hoover” on the poster, which is no longer proudly displayed, but rather folded like origami and stained at the bottom. Its state seems to presage President Hoover’s sinking reputation once the Depression was underway, although Evans could not have known this in 1929. A small, faded flower arrangement on the sill reinforces the impression of a loss of hope and time moving on.

Walker Evans, Political Poster, Massachusetts Village, 1929, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Murray H. Bring), 2015.19.4232

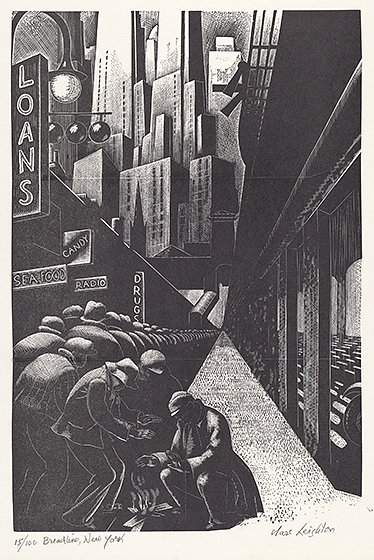

Compare this image of a Depression-era breadline to Walker Evans’s The Breadline, 1933. Look at specific parts of the scene: How are the people in the breadline portrayed? What is the setting? The season? Support your responses with specific evidence from the pictures. Think about differences in medium (wood engraving versus photography), in composition (arrangement of shapes and forms), and style (realistic or stylized). Take note of specific features such as facial expressions, words included in the image, etc.

The artist Clare Leighton was born in England and later became an American citizen. She was a specialist in a distinct type of woodblock printing called wood engraving, which allows the artist to create very fine lines and details. Typically, woodblock printing is characterized by rougher, more expressive lines (see the Pinterest board for an example, Fred Becker’s Rapid Transit, c. 1937). Wood engravers usually cut their designs into a very hard wood like boxwood. Typically, they emphasize the use of white, or “negative” line, to create an image, rather than black line (as in drawing). You can get a sense of what this approach is like by drawing on a black scratchboard with a white underlay.

Clare Leighton, Breadline, New York, 1932, wood engraving in black on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.3119

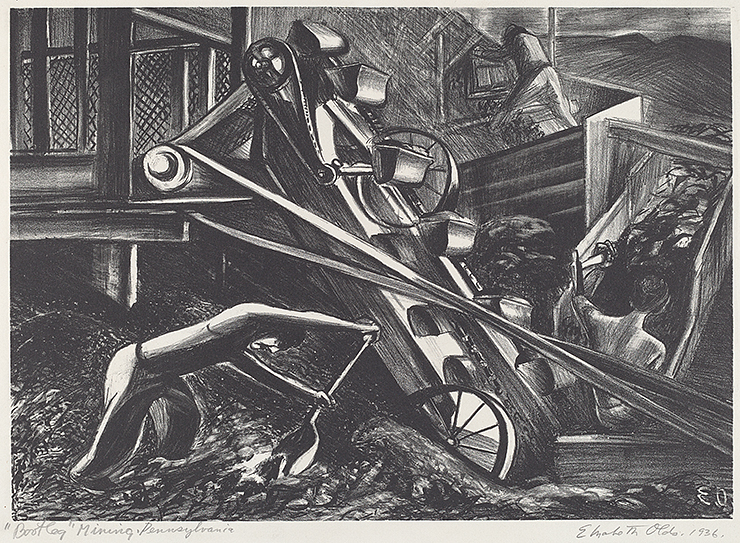

After a day’s work, coal miners in Pennsylvania and elsewhere would often “glean” coal for personal use—with the tacit permission of mine managers. However, worker layoffs during the Depression due to decreased demand for coal and the automation of coal mining led to a huge increase in bootleg—or illegal—mining practices. Laid-off workers returned to mines without permission to dig or collect coal on their own and then sold the bootlegged coal on the open market. The economy of bootlegged coal became big business, with estimates of up to 100,000 people in Pennsylvania living off the practice. Oral history records one miner stating, “We ‘steal’ coal in order to keep from becoming thieves and hold-up men, which, to keep alive, we probably would be forced to become if we didn’t have these holes” (Louis Adamic, “The Great Bootleg Coal Industry,” originally published in The Nation, 1934).

Elizabeth Olds vividly illustrates the situation: the hulking machinery despised by the miners sits idle, while men work with a shovel, pickax, and crate to dig the coal manually.

Elizabeth Olds, Bootleg Mining, Pennsylvania, 1936, lithograph, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.3787

Walker Evans worked for an agency of the Works Progress Administration, the Farm Security Administration, from 1935 to 1937. He traveled across the rural South to photograph the effects of the Depression. This house, with its classical columns and imposing form, was once grand. Yet ultimately, it was subject to the same destructive economic and environmental forces that devastated plantations and farms small and large throughout the United States. It also appears to symbolize the final demise of a way of life built on the labor of enslaved people.

Walker Evans, Abandoned Ante-Bellum Plantation House, Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1936, gelatin silver print, Robert B. Menschel Fund, 1989.69.11

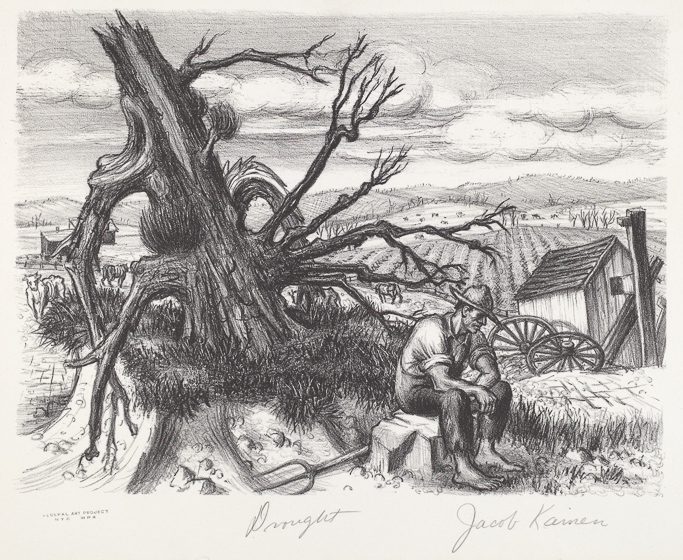

Many artists created images that addressed the environmental devastation that occurred during the Depression. The effects of the bad economy were magnified for agricultural workers and American Indians living on reservations, whose Native lands were overgrazed by livestock permitted there by federal rules, and vulnerable to erosion. In Jacob Kainen’s work, what signs do you see in the picture that offer clues to the state of the environment? You may notice the farmer’s downcast appearance as well as the twisted, dead tree, sandy-looking soil, bony livestock, and sparse vegetation in the fields. Discarded wagon wheels may indicate there is nothing to harvest or transport.

Jacob Kainen, Federal Art Project (New York City), Drought, 1935, lithograph, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2754

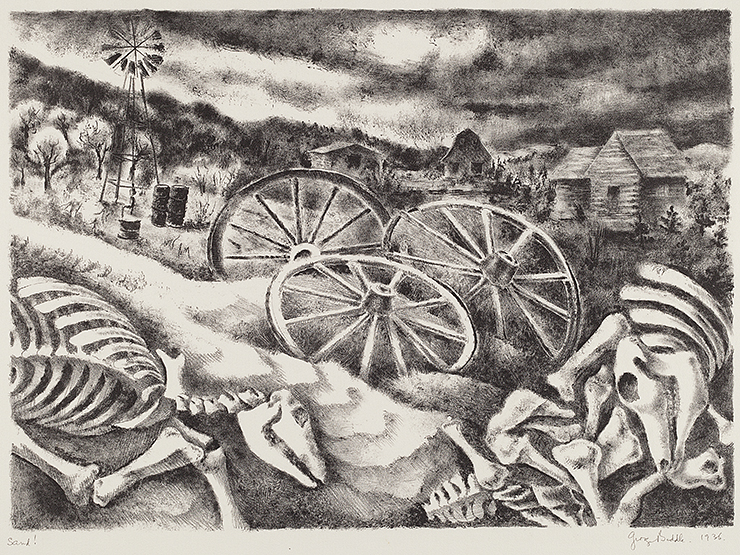

The imagery in Biddle’s Sand! and Kainen’s Drought is similar; notice the placement of the horizon line, gathering storm or dust clouds, and the use of the wagon wheel motif, which may symbolize the halt of progress and inability to move on from difficulties. Biddle’s work offers more explicit imagery—suggesting the bones of domestic livestock that withered from starvation. Biddle studied the art of Mexican muralists who frequently used death imagery and Sand!may reflect their influence. Biddle was also instrumental in advising Franklin Delano Roosevelt to start a program paying unemployed artists a living wage to create images reflecting aspects of American life, which eventually became the Federal Art Program.

George Biddle, Sand!, 1936, lithograph, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.903

This house is not located on the seashore, but in the middle of Nebraska. Photographers working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) took images such as this one to both document and publicize the plight of farmers in the news media—newspapers and magazines at that time—and help the public understand the effects of the drought, the Depression, and resettlement programs. They also sought to influence policy and budget decisions in Washington, DC. Many of their photographs are now in museums, but they were not considered art at the time of their making. Today, the 80,000 images taken by FSA photographers form an important archive about the Depression years and the extreme environmental conditions that occurred due to poor agricultural practices, producing erosion, combined with a persistent lack of rainfall.

Wright Morris, Nebraska Farm House, 1940, gelatin silver print, Robert B. Menschel Fund, 1997.32.1

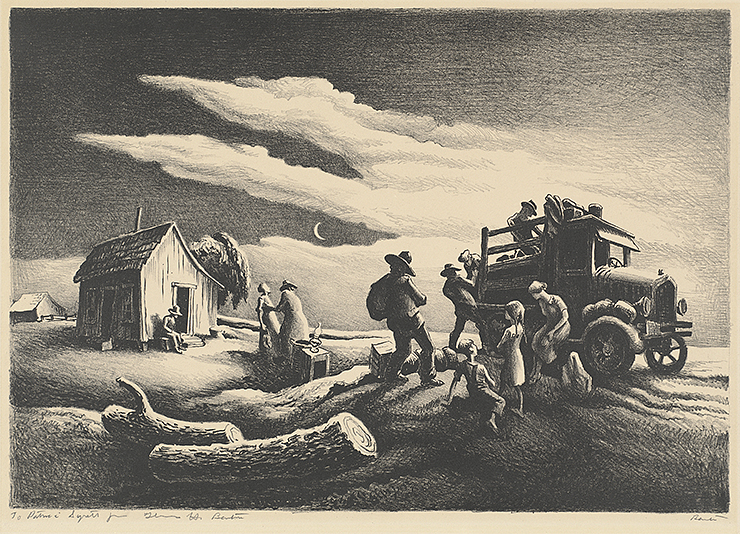

John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel, The Grapes of Wrath, was inspired by the real-life tribulations that the author observed in his native California. In the novel, the Joad family abandons their Oklahoma farm due to drought and seeks a new life in California. Here, the Joads pack their truck as they prepare to depart. The novel relates that the time is just before dawn, with the moon rising in the west and a table with a lantern on it. In Benton’s lithograph, two ominous fingers of clouds reach across from right to left, possibly threatening a stinging dust storm.

Departure of the Joads was part of a series of six prints that were created by Thomas Hart Benton as promotional material for the 1940 film based on the book. The images were blown up to billboard size to advertise the movie.

Thomas Hart Benton, Twentieth-Century Fox Film Corporation, Departure of the Joads, 1939, lithograph in black on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Florian Carr Fund and Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.14

Families from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas abandoned their drought-stricken farms to seek jobs as migrant farmworkers in California. Workers were lucky to find a place in a clean and organized agricultural migrant camp such as this one in California’s Central Valley, one of the first constructed to meet the basic needs of recent arrivals. Other migrants were not so fortunate and formed ad hoc camps near irrigation ditches or roadways, where health and sanitation problems frequently arose. The number of arriving people vastly outnumbered the available jobs or places to live.

Dorothea Lange worked as a portrait photographer in San Francisco for a decade before pursuing her interest in documenting social justice issues, first with the California State Emergency Relief Administration and then with the Federal Resettlement Agency, which became the Farm Security Administration. Many of her photographs came to vividly symbolize the economic and social issues of her time.

Dorothea Lange, Farm Security Administration camp for migrant agricultural workers at Shafter, California, June 1938, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Joshua P. Smith), 2015.19.4298

Stephen Mopope (Kiowa Tribe) depicted ceremonial dance and other aspects of the Plains Indians’ culture. Mopope’s artistic talent was recognized early on the Oklahoma reservation where he grew up. He trained in techniques of painting on hides used for garments and tipis (his traditional Kiowa name was Qued Koi, which means “Painted Robe”) and also was a practiced dancer and musician. Mopope and four other artists, who later became known as the Kiowa Five, attended the University of Oklahoma School of Art during the late 1920s, among the first Native Americans to do so. The Five participated in exhibitions in the United States and abroad and later created a portfolio of prints produced in Paris, of which #17 (Red Dancer) and the next image, #19 (Three Dancers), are a part.

The works were made with a print-making technique known as pochoir, or hand-colored stenciling. Stencils are created by cutting out a design from a rigid material such as cardboard, placing it over another surface, and applying color over the cut areas to produce an image. A stencil permits the production of multiple images, which vary with the materials or colors used each time. Try making your own pochoir and repeat the process with different colors or on different types of surfaces.

Stephen Mopope, #17 (Red Dancer), c. 1940s, pochoir, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.450

Kiowa Native American art often depicts the ceremonial dances, events, and symbolizes the beliefs that reflected the culture. Stephen Mopope, a Kiowa artist, dancer, and musician, grew up on a reservation in the Southwest U.S. where he was trained in the arts by his uncles who were also prominent Kiowa artists. Later, at the University of Oklahoma School of Art, he blended the traditional art skills he had learned with European training, including painting on media such as paper, canvas, and in a mural format.

The technique that Mopope used to create the two works represented in this set is known as pochoir, or hand-colored stenciling, a printmaking method. Although stenciling is centuries old and practiced in numerous cultures, the term pochoirwas first popularized in France in the 1920s in graphic arts and illustration. Mopope and the Kiowa group developed what became known as the flat style, in evidence here, which relates to the techniques used to paint on hides (used for ceremonial robes and tipis) to make the imagery graphically legible.

Mopope’s experience translated well to the public art murals he painted for Andarko, Oklahoma Post Office on Kiowa land under the Federal Art Program and for the Department of the Interior building in Washington, DC (where they may be seen today). Think about how public art murals painted on a wall might be different from a portable painting on canvas – what factors might an artist take into account?

See the related Pinterest board for imagery of the Washington, DC, murals.

Stephen Mopope, #19 (Three Dancers), c. 1940s, pochoir, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.449

Artists during the Depression portrayed what they saw around them in different ways, not all of them realistic. Influences such as the urban landscape, music, and the work of other artists, like that of the cubists, also shaped how they saw the world around them. Artists strived to depict not only sights, but sounds, feelings, and experiences of life as it was lived.

The subject of Leon Bibel’s screenprint depicts what may have been an everyday sight on New York City streets: a pushcart vendor selling food, in this case franks and lemonade. How is this commonplace scene portrayed differently from a realistic rendering? Consider: the buildings tilting at different angles, the flat areas of color, the wavelike swoop of the curb, the cart’s umbrella split in two by a building, and how the colors of the vendor and the scene are the same, as if he himself is a feature of this landscape.

Leon Bibel, Red Hot Franks, 1938, screenprint, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.888

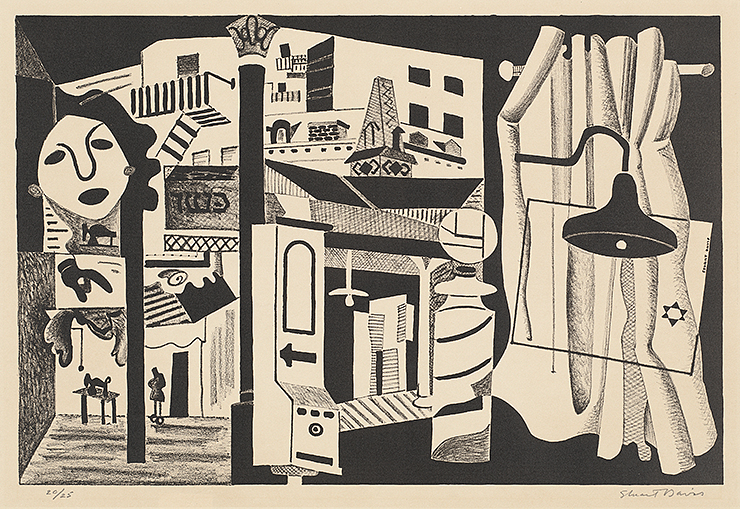

Stuart Davis worked in New York City, whose skyline was growing and changing, adding high-rises, bridges, and transit lines, into which people were funneled and came into proximity with one another in new, impersonal ways. If you’ve ridden a bus, subway, or elevator, you have had such an experience.

Stuart Davis’s lithograph is inspired by the “el” or elevated train line (many in New York City were dismantled to make way for current day subway lines). Describe what you see in the image: What do you recognize and what seems unfamiliar? How might this image relate to the experience of riding the elevated train, or walking near it as it zoomed by overhead?

On the Pinterest board, you can see a photograph by Berenice Abbott, Jefferson Market Court, 1935, that shows a view of the El that may have inspired Stuart.

Stuart Davis, Sixth Avenue El, 1931, lithograph in black on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Florian Carr Fund and Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.52

Grant Wood, who was born and lived most of his life in Iowa, worked as an artist with the Works Progress Administration’s Public Works of Art Project (PWAP, a predecessor of the Federal Art Project). He created murals, notably for Iowa State University’s library, that pictured the virtues of rural life. Wood also served as the director of PWAP in Iowa, coordinating public art projects across the state. Please see the Pinterest board for images of the Iowa State mural that Wood completed.

Wood’s pictures of rolling and verdant farmlands, which have an idealized, dreamlike quality, depart from the images of drought and farm devastation that many WPA-era artists created. By 1939, the Dust Bowl and drought had subsided (it lasted from about 1931 to 1937) and the economy was benefiting from WPA investment in restoring agricultural land and jobs in public works, as well as the start of World War II production. How might this image symbolize new hope in America?

Grant Wood, New Road, 1939, oil on canvas on paperboard mounted on hardboard, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Irwin Strasburger, 1982.7.2

Automats were an early kind of self-service restaurant that offered cheap food to eat in a cafeteria or to take away. Patrons inserted coins next to a window containing their choice of food, and the door unlocked, permitting them to remove it. Automats were the first fast-food restaurants and they opened in urban environments where a lot of people needed to find food quickly and cheaply. The popularity of automats peaked during the Great Depression.

In 1935, Berenice Abbott proposed and directed a project for the WPA’s Federal Art Project called “Changing New York.” Her ambition was to photo-document New York City, which was rapidly modernizing with skyscrapers; new, often WPA-funded infrastructure such as subway lines, bridges, and tunnels; and novel types of shops and conveniences, such as this automat. Abbott also documented aspects of old New York that were being razed to make way for the new. Her work was published in a book of the same name, which was distributed to New York City high schools, libraries, and public institutions.

Berenice Abbott, Automat, 977 Eighth Avenue, Manhattan, 1936, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 1996.6.1

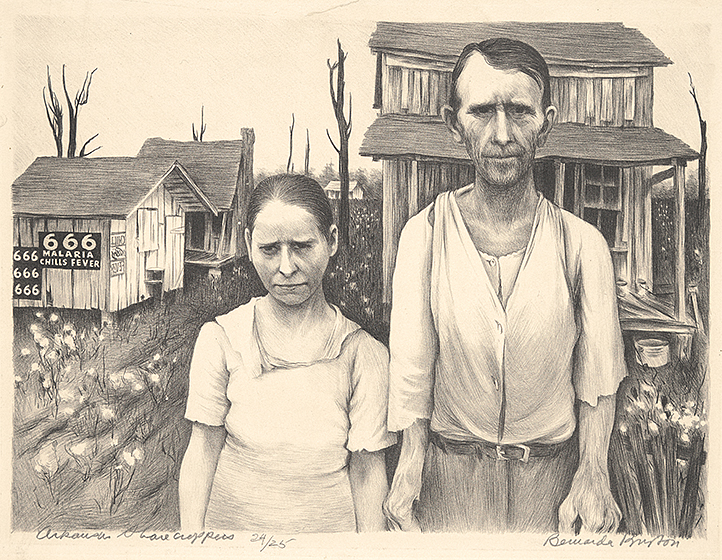

This print by Bernarda Bryson and the following photograph by Gordon Parks are each inspired by Grant Wood’s famous painting, American Gothic, 1930. American Gothic portrays an austere and prim farmer couple outside their clapboard house (which features a pointed “Gothic” window). You can see an image of Wood’s painting on the related Pinterest board (and a different work by Wood elsewhere in this slideshow).

The couple in Bryson’s lithograph stand in a similar frontal pose, but their appearance, and that of their home, is shabby and rickety in contrast to Wood’s painting. Signage behind them on some outbuildings refers to “malaria, chills, and fever” along with repeated use of “666.” Bryson was the companion of another artist who participated in WPA programs, Ben Shahn. They worked together to document aspects of a disappearing rural America.

Bernarda Bryson, Arkansas Sharecroppers, 1935–1936, lithograph, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.4357

Gordon Parks, a photographer, musician, and filmmaker, created this iconic image that also makes reference to Grant Wood’s painting, American Gothic, 1930. While he lived in Washington, DC, working for WPA programs, Parks created a series of photographs about the life of Ella Watson. Watson was an ordinary woman who worked in housekeeping for the federal government (in the offices that housed the Farm Security Administration) in Washington, DC, to support her family. Parks photographed Watson’s life, both at work and at home, extensively. Here, she alone assumes the frontal pose of Wood’s painting, missing a partner, with a mop or broom in place of a pitchfork.

The work of Bernarda Bryson (previous slide) and Parks poses questions about the promise of and disappointments in pursuit of the American dream, and to whom it is available.

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Government Charwoman (American Gothic), July 1942, gelatin silver print, printed later, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2016.117.104

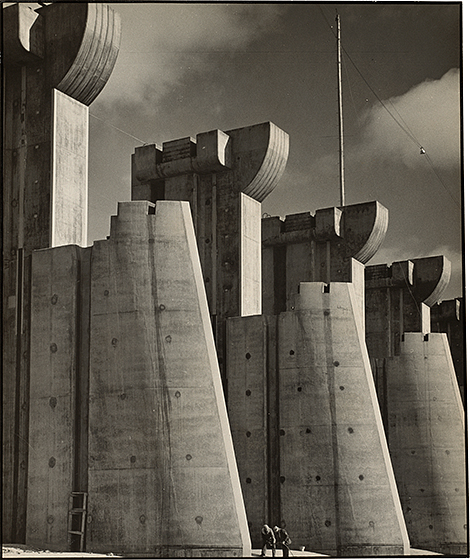

Margaret Bourke-White’s photo of the Fort Peck Dam under construction was famous—it graced the cover of the first issue of Life magazine in 1936. (See the related Pinterest board for a picture of the magazine cover.) The hulking cast concrete piers, supports for an elevated roadway over the dam’s spillway, almost look like abstract sculptures. Bourke-White maximized their visual drama by including figures at the bottom to show the scale of the piers and the dynamic diagonal line in which they are arrayed, as if marching forward. The photo captures the fascination with the dramatic new structures of modern life.

Margaret Bourke-White, Fort Peck Dam, Montana, 1936, gelatin silver print, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2014.113.1

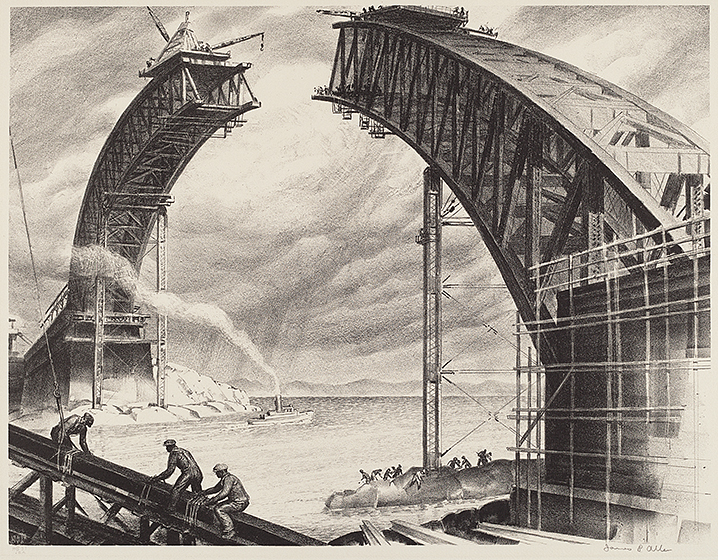

The Bayonne Bridge is pictured here under construction as a pre-WPA project. (It was completed in 1931.) The bridge connects Bayonne, New Jersey, with Staten Island, New York City; below, ships pass back and forth, to and from the Port of Newark. Following its construction, numerous bridges and other elements of infrastructure were funded and built through WPA programs and continue to serve as public amenities today. WPA artists documented and made art inspired by the urban landscape to create positive images of progress in American society and the economy. Bayonne Bridge continues to be in service today and in 2017 it was lifted by 64 feet in order to accommodate larger ships passing underneath. Please see the related Pinterest board for an image of how the bridge looks today.

James E. Allen, Arch of Steel, 1937, lithograph in black, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.644

From 1934 to 1938, the Works Progress Administration assigned workers to make improvements to New York’s Central Park, which included clearing dead trees; building new paths and walls; seeding and reviving the landscaping; and placing amenities like benches, trash cans, lighting, and drinking fountains throughout the park, many of which are still in use today. Artists also working for the WPA documented and created images of the projects and improvements being made to public spaces.

Gifford Beal, Gathering Brush, Central Park, 1934, drypoint in black on laid paper, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Mary E. Maxwell Fund), 2015.19.376

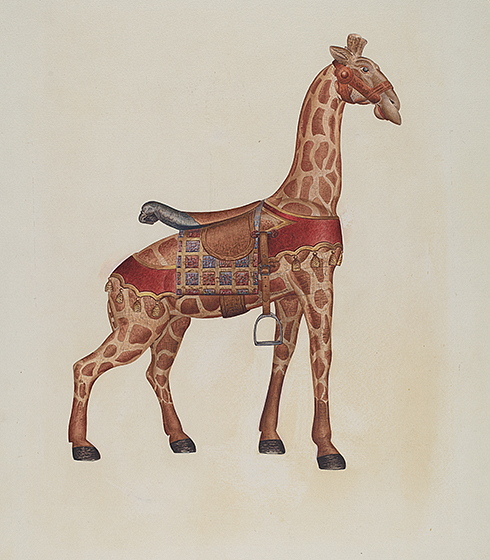

This drawing is one of thousands that artists employed by the Federal Art Project made for the Index of American Design (IAD). The IAD compiled detailed drawings of the well-crafted, everyday objects that represented American material culture from colonial times to about 1890. Objects illustrated included examples of folk art, decorative arts (furniture, rugs, ceramics, quilts, etc.), clothing, signs, and household objects—such as weather vanes, piggy banks, tools, puppets, and this merry-go-round giraffe. Each artist drew from the actual object, whose dimensions were often recorded alongside information about the drawing itself.

The IAD sought to establish a record and history of American design that reflected the country’s unique history, origins, and diverse people and places. It showcased the ingenuity, pragmatism, and pride craftspeople took in their work, and sought to foster people’s pride in those accomplishments.

Henry Tomaszewski, Carousel Giraffe, c. 1939, watercolor and graphite on paperboard, Index of American Design, 1943.8.17121

Drawings made for the Index of American Design project during the Depression offer a valuable record of not only arts and crafts, but the handmade ordinary objects used in everyday life–a washboard, jug, carriage, toy, saddle, or hammer—from colonial times until about 1890. By the 1930s, the pace of modernization, with its increasing reliance on mass-produced commodities, prompted IAD program administrators to seek to document an earlier way of life in which American craftspeople produced by hand all the things needed for living, one by one. The IAD also generated needed jobs for artists, administrators, and researchers. Finely crafted objects, such as this delicate Shaker-style woven and fabric hat and utilitarian, functional items like an ox-cart expressed the range of American design.

This drawing represents an example among the nearly 22,000 that were produced by a team of 400 artists working in 36 states. The planned book—to be distributed to public schools and libraries around the country—was never published as its funding was appropriated for the World War II effort. However, exhibitions of the completed drawings were shown in department stores, community arts centers, and museums around the country. The National Gallery of Art is the largest repository of these drawings, many of which can be viewed online.

Orville A. Carroll, Bonnet, 1935/1942, watercolor, graphite, and gouache on paperboard, Index of American Design, 1943.8.16810

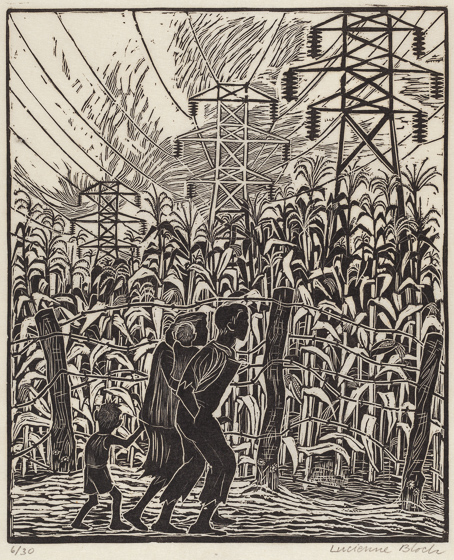

This family of four, who appear tired and bent over, with ragged clothing and bare feet, pass before a field of abundant corn and soaring electrical lines overhead. The picture on one hand represents hope and recovery from the Depression—electricity was made available to many more Americans as part of WPA infrastructure projects, and the Farm Security Administration of the period provided assistance to farmers. However, a fence separates the family from these resources, which are inaccessible to them. The image may comment on the lack of equity in the distribution of such life-sustaining resources to families of color. Lucienne Bloch studied with and was an assistant to Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, working with him on major commissions in Detroit and New York City. She also completed a mural for a women’s detention facility in New York City, entitled Life Cycle of a Woman, 1935.

Lucienne Bloch, Land of Plenty, 1936, woodcut in black on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.944

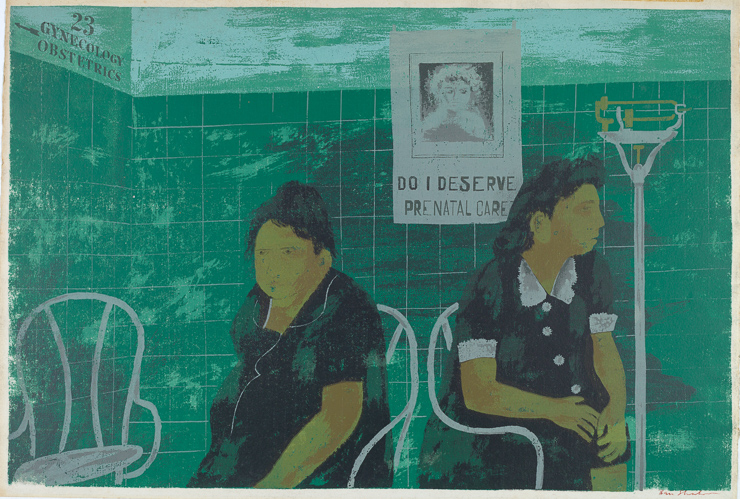

This image of two women in a doctor’s waiting room at a hospital or clinic was an unusual, and even taboo, choice of subject. While today we are accustomed to open discussions about pregnancy and associated health care, in the 1940s (and until the 1960s), such subjects were not publicly discussed. A poster behind the women asks, “Do I deserve prenatal care,” suggesting that some might answer “no.” The two women, who wear maid uniforms typical of the period, appear distracted and disconnected from one another. The ambience of the green, tiled room is grim and unwelcoming.

Ben Shahn is known as a social realist, or artist who depicts the conditions and struggles of working-class people. He also worked with Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, whose work similarly focused on the lives of ordinary people and women’s experiences. Shahn painted murals for the Federal Art Project and also served as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, documenting the plight of agricultural workers. He was married to artist Bernarda Bryson, whose work is also featured in this resource.

Ben Shahn, Prenatal Clinic, 1941, screenprint, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.4345

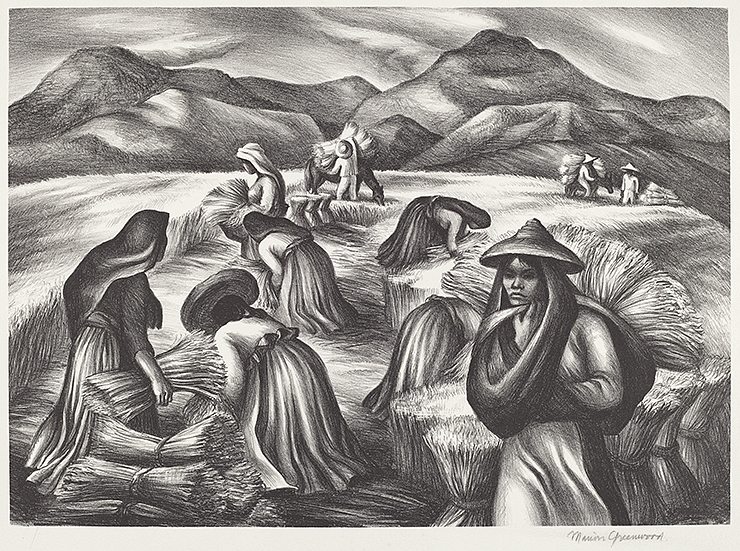

Marion Greenwood, born in Brooklyn to a family of artists, began her art studies early. By age 15 she was enrolled at the Art Students League of New York. She established a successful portrait-painting practice while still young, an endeavor that financed her subsequent travels around the United States, Europe, and Mexico. Greenwood first went to Mexico in 1932 and was commissioned to create murals for the Mexican government, sometimes traveling with her sister Grace, also an artist. She returned to the United States around 1936 and was commissioned to create murals for the Department of the Treasury’s Section of Fine Arts and the Federal Art Project.

This image reflects Greenwood’s association and familiarity with Mexican themes. Mexican Harvest depicts indigenous women gathering wheat beneath a mountainous landscape. In the background, men also dressed in traditional garb load wheat onto the backs of horses or donkeys. Men and women work side by side as equals, laboring to bring in the life-sustaining harvest.

Marion Greenwood, Associated American Artists, Mexican Harvest, 1941, lithograph in black on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2239

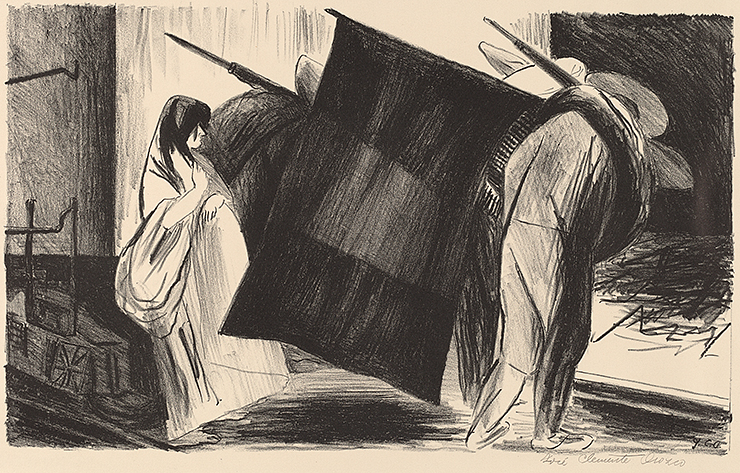

Mexican artists such as José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros played an important role in influencing the course of art in the United States during the Great Depression. During the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), these artists and others were commissioned by the government to create images intended to stoke national pride in Mexican heritage and identity. The artists depicted the revolution’s humble heroes: working-class people; campesinos, or farmers; and the lives of indigenous people, long treated as an underclass by the dominant culture. Here, campesinos in traditional dress, armed with rifles slung over their shoulders, bear the new Mexican flag. A draped pregnant woman stands nearby, possibly symbolizing the birth of a new era for ordinary Mexicans.

José Clemente Orozco, George C. Miller, Flag (Bandera), 1928, lithograph, Rosenwald Collection, 1944.2.45

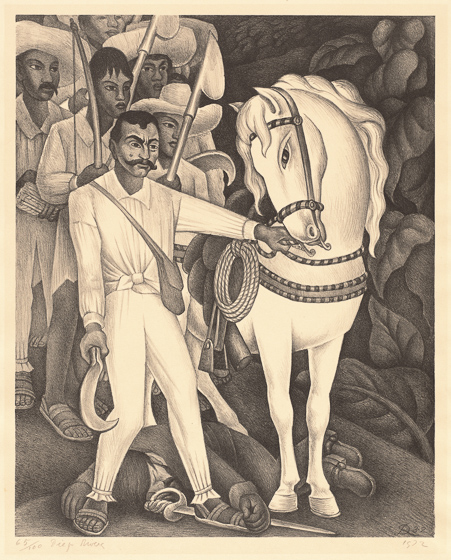

This image memorializes Emiliano Zapata (1879–1919), a folk hero of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). Diego Rivera rendered this image of Zapata three times. The first was for a public mural he painted in Cuernavaca, commissioned by the Mexican government in 1929. Its purpose was to instruct illiterate Mexicans about the history of the Mexican Revolution. In 1931, Rivera painted a copy for a portable fresco he made for a solo exhibition of his art held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Finally, Rivera created this lithograph version.

Zapata stands over the slain body of a hacienda owner, or oppressor. Campesinos, farmworkers, line up behind him with only their farming implements as weapons. The revolutionary Zapata was a charro, or cowboy, and is usually pictured in flamboyant dress. Here, however, he is dressed as a peasant in solidarity with the farmers, for whom he seeks landownership reform. The Cuernavaca murals were Rivera’s first mural commissions from the Mexican government; they sought to illustrate the cultural history and new values of Mexico through art. The Mexican program provided a model for the United States in the 1930s, demonstrating how government-commissioned art could foster a sense of national pride.

Diego Rivera, Viva Zapata, 1932, lithograph in black on Rives BFK paper, Gift of Mrs. Robert A. Hauslohner, 1990.106.51