Civil Rights Movement

The photograph seen here is of two water fountains: one marked “white” and one marked “colored.” Water fountains became symbols of the segregation that permeated all parts of life in the South. This image did not show direct physical violence; instead it demonstrated how Jim Crow laws, which were made at a state and local level in order to enforce segregation, influenced everyday activities such as the simple act of taking a drink of water.

Danny Lyon was a photographer from New York who hitchhiked to Illinois in 1962 in order to document the desegregation movement that was underway there. He was recruited by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as their first staff photographer. Lyon spent two years documenting segregation, racial violence, and demonstrations.

Take a long look at the details in this photograph. Why might this image be important to the civil rights movement?

Danny Lyon, Segregated Drinking Fountains, County Courthouse, Albany, Georgia, 1962, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Friends of the Corcoran), 2015.19.4465

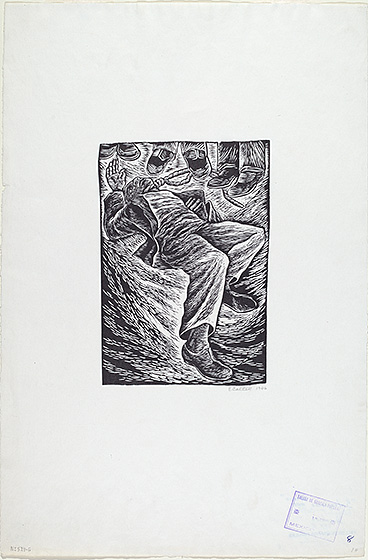

Elizabeth Catlett created a series of 15 linocuts—prints made by cutting a relief drawing into a piece of linoleum—titled I Am the Negro Woman. The series featured both famous and everyday African American women, with accompanying texts celebrating their courage and determination. Catlett’s prints called attention to the daily struggles of African Americans, especially in the South.

Look carefully at the details of this print. What details are included and what details are left out? What is your vantage point as the viewer? This linocut depicts a lynching, the unlawful murder of an African American at the hands of white Americans, in response to an alleged crime or violation of social norms. Lynching was a constant threat that plagued the African American community from the time of emancipation in the late 19th century into the civil rights era.

Discuss the meaning of the title …and a special fear for my loved ones. What other fears might people have felt at this time? What fears might people have now?

Elizabeth Catlett, ...and a special fear for my loved ones, 1946, linocut, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Florian Carr Fund and Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.36

“I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapons against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty.” —Gordon Parks

In 1956 Life magazine published a photo-essay titled “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” featuring 26 color images by staff photographer Gordon Parks. These photographs exposed white Americans to the realities of racial segregation by focusing on the day-to-day activities of families in Alabama.

Jim Crow laws—common in many states from the 1890s to the 1960s, especially in the South—mandated the segregation of public spaces, including bathrooms, drinking fountains, restaurants, public transportation, schools, and theaters, such as the one shown here with its neon “colored entrance” sign above Joanne Thornton Wilson and her niece, Shirley Anne Kirksey. Parks’s photo-essay documented the impact of Jim Crow laws on individuals. Rather than focusing on boycotts, demonstrations, or the brutality that marked the fight for justice, Parks captured intimate views of inequality. He also wanted to undo racial stereotypes of African Americans by providing positive accounts of real people.

What “weapons” can you use to fight for what you believe in?

Gordon Parks, Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, printed later, silver dye bleach print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2016.117.195

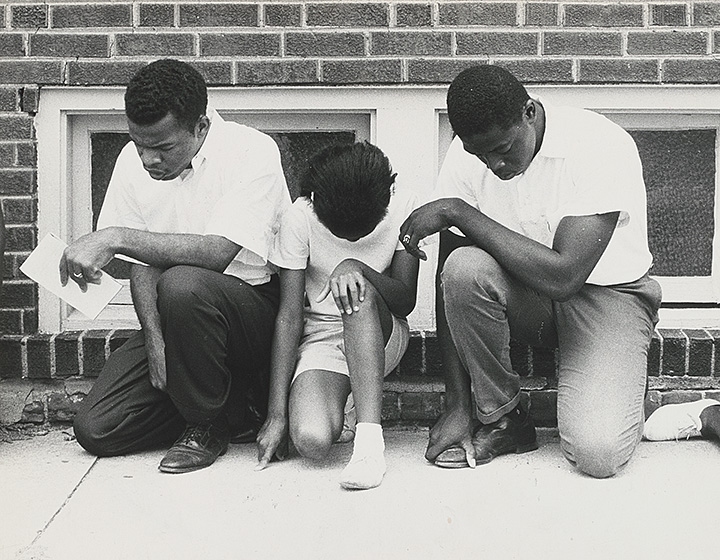

In 1962 photographer Danny Lyon captured three young African Americans protesting through prayer in front of a “whites-only” swimming pool and recreational facility in Cairo, Illinois. Their demonstration was part of a larger effort to integrate businesses and other spaces in the town. Lyon was involved in the movement and developed strong relationships with members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a group of young people who were committed to full-time grassroots organization. Through his involvement, Lyon captured many aspects of SNCC’s efforts, from prayer demonstrations led by a young John Lewis (at left) to violence suffered by students at the hands of the National Guard. John Lewis continued his activism for many years and was elected to the US Congress in 1986, where he continues to serve as a representative for Georgia in the House of Representatives.

SNCC used this 1962 photograph to develop its public image in support of expanded rights for African Americans. For example, it was used as part of a poster series; printed in bold below the demonstrators’ photograph were the words “come let us build a new world together.”

What does “come let us build a new world together” mean to you? What other slogans or images have inspired you to act? How is kneeling used as a form of protest today?

Danny Lyon, John Lewis and Colleagues, Prayer Demonstration at a Segregated Swimming Pool, Cairo, Illinois, 1962, printed 1969, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase), 2015.19.4466

Arthur Ellis was a leading photojournalist for the Washington Post from 1930 through the early 1970s. He captured a period of dramatic change across the country through the lens of the nation’s capital.

Here Ellis has captured one of many demonstrations during the civil rights movement, a 1963 protest demanding equitable housing opportunities and fair labor laws. The fight for equal housing would continue for five more years until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was passed. This act prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, or sex, expanding on the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Choose one person in the photograph. Imagine you are that person. What might you see, feel, hear, taste, or smell? How might it feel to be in this crowd?

Arthur Ellis, Civil Rights Demonstration for Fair Employment and Housing Legislation, Washington, D.C., June 14, 1963, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Estate of Frederica Ellis, wife of Arthur J. Ellis), 2015.19.5005

Congressman John Lewis befriended photographer Danny Lyon in the 1960s, when they were both working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization that aimed to desegregate the United States. In 2002 Lewis described this picture, in which National Guard troops dragged Clifford Vaughs, an activist, out of a sit-in:

“We had discussions about the role of photography in SNCC, but it was only later that I really understood what we were trying to do. We had to find a way to help educate and sensitize people, especially non-Southerners. We were trying to put a face on the movement, to make it real, to make it very plain and simple to ordinary people. We wanted to say, ‘This is what is happening.’ Many people across the country saw all these unbelievable photographs in newspapers or magazines and were inspired by them….They became a tool to educate, inspire, and enlighten the public.”

What strikes you about this photograph? Choose one person in the image and consider that person’s point of view. What might that person be thinking?

Danny Lyon, Clifford Vaughs, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Photographer, Arrested by the National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland, 1964, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Friends of the Corcoran), 2015.19.4463

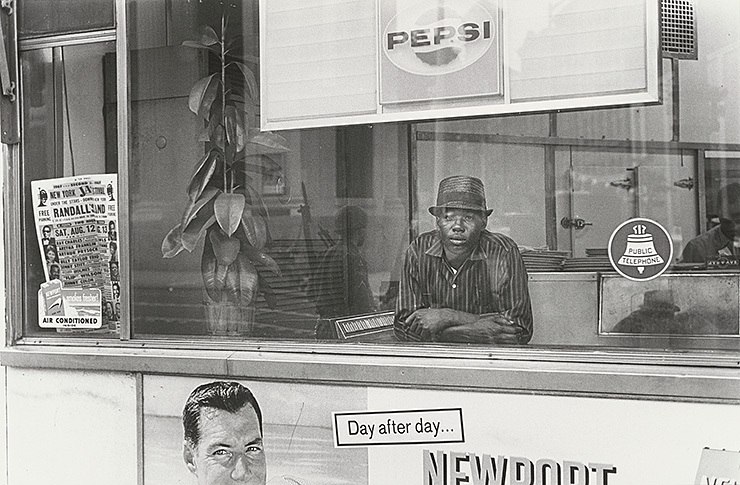

This photograph was taken during what was known as the “long, hot summer of 1967.” It was a season marked by racial tensions that exploded into a series of deadly riots in California, New York, Michigan, and New Jersey. The Newark riots, the subject of this photo, erupted on July 12 when residents of a large public housing development witnessed the beating of an African American cab driver by white police officers. Over the course of several days, 26 people were killed (making it among the deadliest of the riots), another 700 were injured, and entire blocks were burned to the ground, causing millions of dollars in damages.

Benedict J. Fernandez made a series of artistic choices in this photograph. What details did he include? What can you see through the window? What do you think Fernandez is trying to convey in this photograph?

Benedict J. Fernandez, Newark Riots, Day After Day, 1967, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Alexander Wolf Levy), 2016.22.121

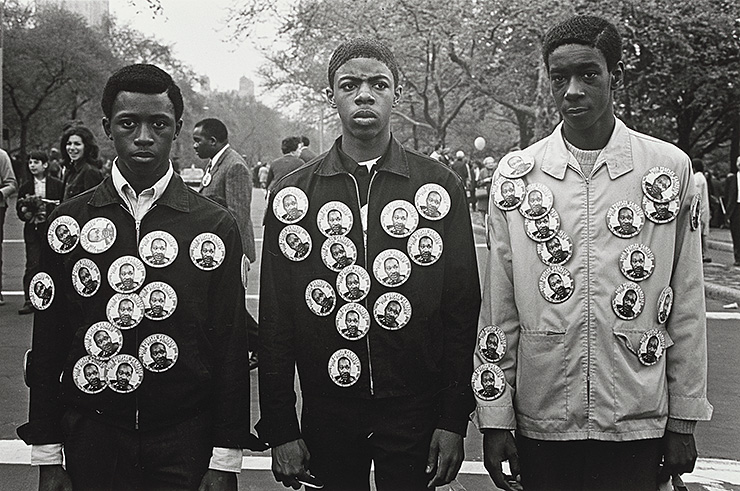

On April 5, 1968, a crowd of New Yorkers, including several thousand high school students, gathered in Central Park. They came together to mourn the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who had been shot and killed the previous day. The mourners listened to several speeches from local leaders before marching down Broadway to city hall. This was largely a peaceful demonstration in respect for King’s belief in nonviolence.

Consider the title of this photograph. What do you think the photographer, Benedict J. Fernandez, meant by this? Look at the facial expressions of the three young men. How would you describe them?

Benedict J. Fernandez, Memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr., Central Park, New York, April 1968, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Michael S. Engl), 2016.22.112

In February 1968, over 700 African American sanitation workers went on strike in Memphis to advocate for higher wages and protest poor working conditions following the death of two workers. This strike, known as the Memphis Sanitation Strike, had the support of the local union and lasted over two months. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Memphis to support the strike, and on April 4 he was assassinated. Placards like the ones held by these two men were created for a memorial march held in Memphis four days after King’s assassination. The photographer, Benedict J. Fernandez, had developed a close relationship with King and was an active participant in many of the events where King was present.

Look carefully at this image. What clues are there about what this event was like? Why might Fernandez have chosen this moment to depict?

Benedict J. Fernandez, Memphis, Tennessee, April 1968, printed 1989, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Eastman Kodak Company and Michael S. Engl), 2016.22.104

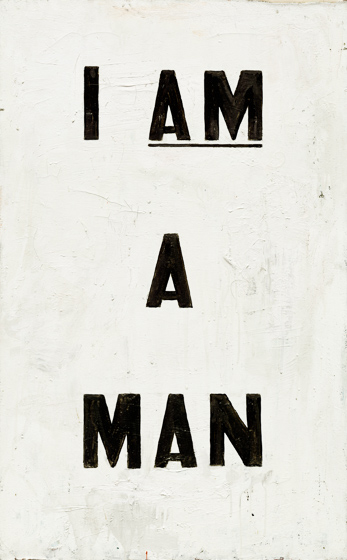

In this photograph, we see two men resting on the steps of a church in Washington, DC. In the foreground, there is an iconic protest sign with the words “I Am a Man.” Another sign, worn by one of the men, says “Honor King: End Racism!”

During the summer of 1968, activists took over the National Mall in order to raise awareness of the widespread effects of poverty. The movement was known as the Poor People’s Campaign. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was a central figure in the campaign, bringing together different groups of people in support of a living wage for all. On June 19, over 150,000 people gathered on the National Mall to support the movement’s goals, culminating with a Solidarity Day rally in celebration of Juneteenth, the historical date of emancipation across the former Confederate States of America. This photograph, captured by Benedict J. Fernandez, is from this summer of 1968 in Washington, DC.

Explore the composition of this photograph and the prominence of the sign in the foreground. What might the photographer want us to know? What story or stories are being told here? What effect do these two slogans have on you?

Benedict J. Fernandez, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington D.C., Summer 1968, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Michael S. Engl), 2016.22.108

Untitled (I Am a Man) is a representation of actual signs carried by over 700 striking African American sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968. Prompted by the wrongful deaths of two coworkers from faulty equipment, the strikers marched to protest low wages and unsafe working conditions. They took up the slogan “I Am a Man,” a variant on the first line of Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952): “I am an invisible man.” By deleting the word “invisible,” the Memphis strikers asserted their presence, making themselves visible in standing up for their rights. This slogan and these signs continued to be used throughout the civil rights movement.

In this work, Glenn Ligon differentiates his painting from the original signs by reorganizing the line breaks and painting the black letters in eye-catching enamel.

This iconic sign—both its language and design—is particularly powerful, as evidenced by its continued use today. It was recently used by groups of children protesting family separation at the US-Mexico border. They edited the text to say, “I Am a Child.” Why do you think this slogan is so powerful?

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988, oil and enamel on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund and Gift of the Artist, 2012.109.1

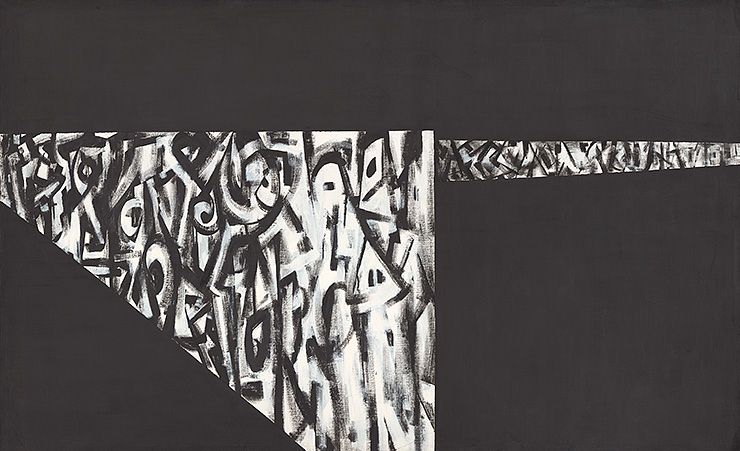

Although there is no official title for this painting, Norman Lewis’s widow reported that he called it Alabama. Its composition reflects and exaggerates the shape of that Southern state, which is a tapering quadrilateral with a “handle” at Mobile, where the United States meets the Gulf of Mexico. In Lewis’s work, there is a sharp contrast between the painting’s two dominant geometric shapes and their black surroundings. The shapes have razor-edged outlines and angles, and are abruptly cropped at the edge of the canvas—forming the profile of a meat cleaver or guillotine. In the larger shape, the hood of a Klansman emerges from a mass of black and white brushstrokes, adding a menacing figure to Lewis’s dramatic composition.

Consider this abstract painting in conjunction with the photographs in this image set. What new insights does this painting give you on the civil rights era? What can this painting tell us that a photograph might not?

Norman Lewis, Untitled (Alabama), 1967, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2009.45.1

On September 15, 1963, four Klansmen bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama; four young girls were killed and two teenage boys were murdered in racially motivated violence following the incident. In 2005 American photographer Dawoud Bey (b. 1953) visited Birmingham to explore the possibility of making artwork to commemorate the event. He created a series, The Birmingham Project, composed of diptychs—works of art on two combined panels. Each diptych pairs a portrait of a young person the same age as one of the victims with a second portrait of an adult 50 years older—the child’s age had she or he survived.

Look carefully at these images. What emotions do they stir up in you? How might these photographs help us to connect the past to the present?

Dawoud Bey, Mary Parker and Caela Cowan, 2012, printed 2014, 2 inkjet prints, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Collectors Committee and the Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2018.12.3.1–2