Introduction

When photography was introduced to the world in 1839, society and culture were on the brink of profound change. In the words of one of its inventors, William Henry Fox Talbot, the new art that directly reproduced nature without the human hand was “a little bit of magic realized.” Almost 20 years later, the critic Lady Eastlake would remark on the camera’s power to harness “the eye of the sun,” so that “photography has become a household word and a household want.” Integrating art and science, photography was a startling invention that created new ways of seeing, experiencing, and understanding the world.

The exhibition features photographs from the medium’s first 50 years, from the earliest photographs in the Gallery’s collection to amateur pictures taken with the Kodak, the first snapshot camera. The objects below highlight some of the new acquisitions featured in The Eye of the Sun and represent a range of subjects and techniques embraced by early photographers.

William Henry Fox Talbot

Winter Trees, Reflected in a Pond, 1841–1842

William Henry Fox Talbot, Winter Trees, Reflected in a Pond, 1841-1842, salted paper print, Purchased as the Gift of the Richard King Mellon Foundation, 2018.6.2

Equally adept in astronomy, chemistry, Egyptology, physics, and philosophy, Talbot is the father of modern photography. He spent years inventing his paper-based photographic process, which involved sensitizing a sheet of paper to light by coating it with a solution of silver salts, exposing it in a camera, and then chemically developing the latent image. This “negative,” which tonally reversed lights and darks, was then placed in direct contact with another sheet of sensitized paper, resulting in a “positive” print. While the rival French process of the daguerreotype, a direct positive image on a silver-coated copper plate, initially found greater popularity, it was Talbot’s negative-positive process that became the foundation of the medium until the advent of digital photography.

Though steeped in the sciences, Talbot grasped the artistic potential of his invention. In his limpid view of the reflection of trees in the lake at Lacock Abbey, his family home where he conducted his experiments, Talbot exploited the massing of highlights and shadows characteristic of the salted paper print. Journeying to France a year or so later, Talbot climbed to the top of one of the towers of Orléans Cathedral. Instead of capturing the entire cathedral, he took advantage of the camera’s ability to frame a detail that was expressive of the larger whole.

William Edward Kilburn

Queen Victoria and Children, January 19, 1852

Queen Victoria, who ascended to the British throne just two years before photography was unveiled, became fascinated by the medium. Over the course of her reign she shrewdly employed portrait photographs of herself and her family to fashion her public image as a monarch for modern times. Upon the death of her husband, Prince Albert, she turned to photography as a way to reach her public, sitting with her children for a portrait by William Bambridge that captures the family in mourning. The

Mary Dillwyn

The Picnic Party, 1854

Mary Dillwyn, The Picnic Party, 1854, salted paper print, Purchased as the Gift of the Richard King Mellon Foundation, 2018.7.23

Generally regarded as the first female photographer in Wales, Mary Dillwyn made salted paper prints in the 1850s that depict flowers, birds, pets, family, and friends. She used a small camera, which shortened exposure times and enabled her to record spontaneous moments and intimate gatherings such as this picnic at Oystermouth Castle. Unlike the formal poses and austere expressions seen in most early photographs, Dillwyn captured the everyday pleasures of elite Victorian families. The young women pictured here likely include her friends Caroline and Dulcie Eden.

Dillwyn grew up in a family of experimental photographers. Her older brother was the pioneering photographer and botanist John Dillwyn Llewelyn. His wife, Emma Talbot Llewelyn, was a cousin of William Henry Fox Talbot, the British inventor of photography on paper. Inspired by these close connections, the Llewelyn family made photography a communal pursuit at their estate of Penllergare, located near Swansea in southern Wales.

Gustave Le Gray

Brig on the Water, 1856

Gustave Le Gray, Brig on the Water, 1856, albumen print, Purchased as the Gift of Diana and Mallory Walker, 2018.5.1

Painter-turned-photographer Gustave Le Gray is notable for achieving a rare level of technical, artistic, and commercial success in the 19th century. In the mid-1850s he produced a groundbreaking series of seascapes, including this albumen print taken off the coast of Normandy. At the time, because photographic emulsions were more sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum, the sky was often overexposed, so that it appeared gray or mottled in prints. To circumvent this limitation, many photographers painted out the sky in the negative, so that it appeared as a bright, blank expanse on the print, sometimes hand-painting clouds into the empty space. Others captured details in both areas by making two negatives—one for the landscape, and a faster one for the sky—to be printed as a single image.

In Brig on the Water Le Gray took a different approach, exploiting the practical limitations of the medium for artistic effect. Rather than optimizing the exposure for the water, he used a shorter exposure to capture the atmospheric details of the clouds and sunlight. The underexposed sea appears dark, its details difficult to discern. This technical manipulation made Le Gray’s daytime view appear to be a seascape at twilight, with the sun slipping behind the clouds and illuminating the horizon. Brig on the Water won both critical and popular acclaim and was widely circulated.

Eugène Cuvelier

Gorges de Franchard - Forêt de Fontainebleau, October 20, 1863

Eugène Cuvelier, Gorges de Franchard - Forêt de Fontainebleau (Franchard Gorges – Fontainebleau Forest), October 20, 1863, salted paper print, Purchased as the Gift of the Richard King Mellon Foundation, 2018.6.1

The forest of Fontainebleau is a bucolic wooded landscape that became a popular day trip from Paris after a railway connected it to the city in the 1850s. It was a favorite of artists, such as the painters Camille Corot, Jean-Francois Millet, and Theodore Rousseau, who gathered at the small town of Barbizon on the outskirts of the forest and, working outdoors, painted the landscape. Cuvelier initially trained as a painter and was part of this artistic milieu, even marrying the daughter of a Barbizon innkeeper who hosted the artists. He brought his training to the new medium of photography, wandering the forest with tripod and camera. Though many of his photographs capture the density of the ancient forest, teeming with detail, he also focused on Fontainebleau’s distinctive rocky plains. One of his images features a lone figure perched atop the rock to impart a sense of scale.

Frederick DeBourg Richards

McAllister's Optical Shop, Philadelphia,

December 12, 1854

Richards simultaneously pursued a career as a landscape painter and a photographer. Opening a commercial studio in 1848 where he offered daguerreotypes, Richards soon adopted paper-based photography in the early 1850s, often photographing the streets and buildings of Philadelphia for the city’s avid antiquarian community. The daguerreotype process was slowly superseded by paper and glass negatives and corresponding paper prints. Yet in 1854 Richards chose the daguerreotype to commemorate an important site in Philadelphia’s photographic history: the building housing McAllister’s Optical Shop. The store had served as a significant gathering spot for the first adopters of the daguerreotype process—chemists, scientists, and mechanical tinkerers—in the heady early experimental years of the medium after its announcement in 1839. Over the next 15 years, John McAllister Jr., who poses in the second story window on the far right, supplied lenses and other equipment to the first generation of photographers. Thriving as the major photographic supplier in the city, when this photograph was taken the store was in the process of relocating to newer and bigger premises nearby. Richards’s elegiac souvenir not only captured the final days of the business before it embarked on its next phase, but also commemorates the heyday of the daguerreotype.

Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg

Assembly of Troops for Napoleon III, Place Bellecour de Lyon, 1860

Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg, Assembly of Troops for Napoleon III, Place Bellecour de Lyon, 1860, albumen print, Purchased as the Gift of Diana and Mallory Walker, 2019.20.3

One of the first to exhibit daguerreotypes in Paris, Richebourg embraced photography in 1839. He made portraits and sold photographic equipment at his Paris shop beginning in 1841, and in the early 1850s he began working with the collodion negative, a process involving sensitizing, exposing, and developing a glass plate coated with salt and collodion. Richebourg exhibited photographs on a range of subjects, including reproductions of art and views of palace interiors. As an official photographer for the Second Empire, he also documented contemporary events. His photographs formed the basis of widely circulated illustrations.

When Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie visited Lyon in August 1860 for the inauguration of the Palace of Commerce, Richebourg captured the assembly of thousands of French troops in the nearby Place Bellecour. Richebourg’s photograph illustrates not only the scale of public ceremony under Napoleon’s regime, but also the symbolic significance of the Palace of Commerce for the prosperity of the city. Napoleon III sought to modernize the French economy by building the necessary infrastructure to support economic growth—from railways and roads that facilitated trade to institutions like Lyon’s Palace of Commerce.

McPherson & Oliver

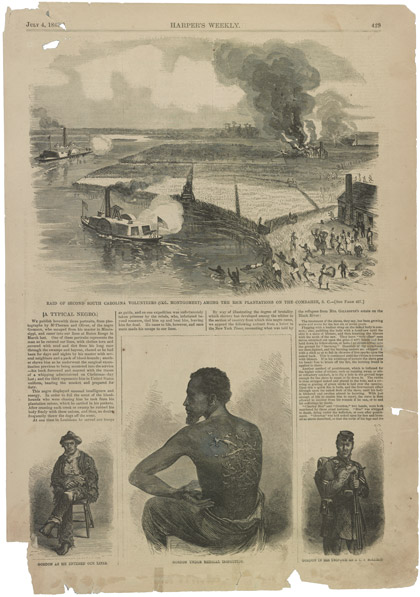

The Scourged Back, c. 1863

Seated with his back exposed, this young man bears scores of raised scars, evidence of the punishing whippings he received as an enslaved man. Most commonly identified as Gordon, but also described as Peter, he is believed to have escaped a plantation in either Mississippi or Louisiana before finding sanctuary in early 1863 at a Union soldiers’ camp in Baton Rouge, where this picture was taken during a medical examination.

Abolitionists circulated this photograph to substantiate their allegations of the brutal mistreatment of enslaved persons and build support for their cause. The photograph was taken by McPherson & Oliver, owners of photography studios in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, and sent to New England, where copies, such as this carte-de-visite, were distributed by other studios. An unidentified writer for the New York Independent said, “This Card Photograph should be multiplied by 100,000, and scattered over the States. It tells the story in a way that even Mrs. [Harriet Beecher] Stowe [author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)], can not approach, because it tells the story to the eye.”

The photograph reached an even wider audience when it was reproduced as an engraving in Harper’s Weekly in July 1863. In that publication it was flanked by two additional illustrations: one depicting Gordon, a fugitive slave, upon arrival in Baton Rouge, with bare feet, tattered clothes, and “covered with mud and dirt from his long race through the swamps and bayous, chased as he had been for days and night by his master and several neighbors and a pack of blood-hounds;” and the other showing what is described as the same young man, now uniformed, after mustering into the Union army. Presented as a tale of resilience, Gordon’s story was intended to elicit sympathy and respect.

African American soldiers began to sit for portraits soon after 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation lifted the ban on their serving in the army. Although President Lincoln initially had misgivings about permitting these men to enlist, he eventually authorized their recruitment. As Frederick Douglass persuasively argued, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth . . . that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” The uniformed portrait of Private Christopher Anderson of Company F 108 of the US Colored Infantry shows a typical formal, proud stance. Taken as part of a group of similar portraits, it was made for an officer. Anderson’s regiment, which included many men formerly enslaved in Louisville, Kentucky, was stationed in Rock Island, Illinois, where the soldiers’ responsibilities included the guarding of Confederate prisoners.

Andrew Joseph Russell

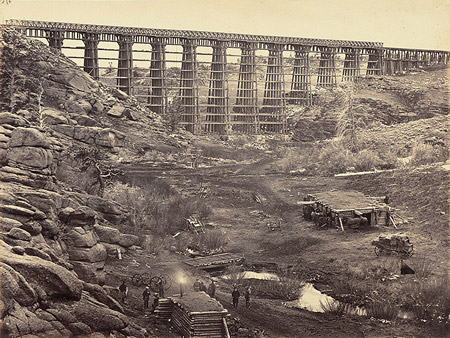

Granite Canon, from the water tank, from The Great West Illustrated in a Series of Photographic Views Across the Continent, 1869

Andrew Joseph Russell, Granite Canon, from the water tank, albumen print from The Great West Illustrated in a Series of Photographic Views Across the Continent, 1869, bound volume, Avalon Fund and New Century Fund, 2016.155.1

Andrew Joseph Russell’s The Great West Illustrated is a landmark of 19th-century American photography. Its powerful pictures of the Wyoming and Utah landscapes celebrated the region’s vast untapped resources and natural beauty and suggested the promise of technological development to promote westward expansion.

Trained as a landscape painter, Russell began his photographic career during the Civil War when he worked for the United States Military Construction Corps documenting the repair and construction of railroads and other engineering projects. After the war Russell was hired as the official photographer for the Union Pacific Railroad, which had recently been granted loans and land to expand the country’s transportation infrastructure with the goal of connecting the Pacific Coast with existing railroads in the East. Union Pacific was charged with the task of laying tracks from Omaha, Nebraska, to Promontory Summit, Utah, where they would eventually be connected with lines being built by Central Pacific Railroad eastward from Sacramento, California.

By 1868, when Russell began his first of three expeditions, Union Pacific had reached Wyoming. Russell was given a railroad car to transport his supplies along the freshly laid tracks that traversed desolate, rugged terrain. He then accompanied workers as they pushed forward over unbuilt sections, where he captured images of a pristine and unfamiliar landscape, as well as signs of industrial growth. His picture of the Dale Creek Bridge—the longest along the Union Pacific route—shows the wooden bridge under construction, with laborers and supplies seen in the foreground. After it was completed, passing trains slowed to a crawl because of the perilous sway of the wooden structure; less than a decade later the bridge had been largely replaced by a sturdier iron construction.

Andrew Joseph Russell, Dale Creek Bridge, from above, albumen print from

Andrew Joseph Russell, High Bluff, Black Buttes, albumen print from

Andrew Joseph Russell, Hanging Rock, foot of Echo Canon, albumen print from

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne

(de Boulogne)

Terror mixed with pain, torture, 1854–1856

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne), Terror mixed with pain, torture, 1854-1856, printed 1862, albumen print, W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg Fund, in Honor of the 25th Anniversary of Photography at the National Gallery of Art, 2015.52.15

A neurologist, physiologist, and photographer, Duchenne conducted a series of experiments in the mid-1850s in which he applied electrical currents to various facial muscles. Convinced that the expressions they induced accurately rendered feelings, he photographed the results to establish a visual lexicon of human emotions. Duchenne’s favorite model was a shoemaker described by the doctor as “a tooth-less man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality and whose facial expression was in perfect agreement with his inoffensive character and his restricted intelligence.”

Using photography to record the effects of electrical stimulation allowed Duchenne to preserve fleeting expressions and then present them to the scientific community, as in his 1862 work The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression. The first published physiological experiments to be illustrated with photographs, the volume includes chapters on the expression of a range of emotions, including pain, attention, terror, sadness, and surprise. Several months later, Duchenne supplemented his scientific findings with an aesthetic section, where his theories took on a more narrative approach, expanding from the focus on isolated facial expressions to include gestures, poses, and background scenery.

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne), Painful memories, 1854-1856, printed 1862, albumen print, W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg Fund, in Honor of the 25th Anniversary of Photography at the National Gallery of Art, 2015.52.9

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne), Expression of severity, 1854-1856, printed 1862, albumen print, W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg Fund, in Honor of the 25th Anniversary of Photography at the National Gallery of Art, 2015.52.4

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne), Attention, attentive gaze (left); Painful attention (right), 1854-1856, printed 1862, albumen print, Eugene L. and Marie-Louise Garbáty Fund, 2015.52.21

Julia Margaret Cameron

A Minstrel Group, 1867

Julia Margaret Cameron, A Minstrel Group, 1867, albumen print, Purchased as the Gift of the Richard King Mellon Foundation, 2018.7.11

Immersed in the intellectual and artistic circles of midcentury Britain, Cameron manipulated focus and light to create poetic pictures rich in references to literature, mythology, and history. Making unprecedented life-size portraits, she defined a new mode of photography that she intended to rival the expressive power of painting and sculpture. Her subjects included her family and servants as well as the literary and cultural giants of her day—the poet Alfred Tennyson was a neighbor and friend who posed for her frequently.

Aside from portraiture, a major part of Cameron’s practice consisted of narrative tableaux—“fancy subjects,” as she called them—that arranged models in elaborate costumes and theatrical poses. A Minstrel Group features her young neighbor Kate Keown dressed as a medieval minstrel. Holding a mandolin, she stands between her sister, Elizabeth, and Cameron’s maid, Mary Ryan. With their props, dress, and expressive gazes, Cameron transforms and elevates her ordinary models into a scene from Victorian poetry. The photograph illustrates Christina Rosetti’s poem “Advent” (1862): “We sing a slow contented song / and knock at Paradise.”

Glossary

Daguerreotype

Announced to the world by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in 1839, the daguerreotype is a photograph produced using a highly polished, silver-coated copper plate that is sensitized with iodine and bromine vapors before being placed in a camera for exposure to sunlight. After it is removed from the camera, the plate is exposed to the fumes of heated mercury, revealing the image. It is then “fixed” to prevent unexposed silver compounds from further development, washed, dried, and often toned with gold. As a direct positive image rather than a print from a negative, the daguerreotype is laterally reversed. Daguerreotypes are characterized by a subtle tonal range and are capable of achieving exacting detail. However, their mirrorlike surface makes the images difficult to see from certain angles.

Paper Negative and Salted Paper Print

Introduced by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1839–1840, the paper negative and salted paper print were the basis for the first practical negative-positive photographic processes. A paper negative is made by coating a sheet of paper with a solution of silver salt to render it light sensitive. Once dry, the sheet is placed in a camera and exposed to sunlight. It is then chemically developed to make the image visible and subsequently fixed, washed, and dried. To make a positive salted paper print, a sheet of paper is first coated with a salt solution of ammonium or sodium chloride. Once it is dry a silver nitrate solution is applied to sensitize the salted paper. When that solution dries the paper is placed in direct contact with a negative in a printing frame and exposed to sunlight, which causes the image to form spontaneously, or “print out.” The print is then washed to remove any unexposed silver salts, fixed, washed again, and dried. Later improvements to the process included oiling or waxing the thin negative paper to increase its transparency, which allowed more detail to be captured in the negative and the salted paper print made from it. Although many salted paper prints have a matte surface, some are coated with wax or varnish, which further enhances detail and imparts a sheen to the paper.

Collodion Negative

Developed by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 and widely adopted by the mid-1850s, the collodion negative was the most common negative process used in the third quarter of the 19th century. A collodion negative is made by coating a glass plate with a salted collodion solution (a liquid made by dissolving gun cotton in ether and alcohol) and then sensitizing the plate by bathing it in a silver nitrate solution. The damp plate is inserted into a camera and exposed to light. After exposure, the plate is removed from the camera and chemically developed to reveal the image. It is subsequently fixed, washed, and dried, and finally coated with varnish. In the mid-1850s, variations on this process were introduced that allowed sensitized plates to be prepared ahead of time rather than just before exposure.

Albumen Print

The dominant print process in the latter half of the 19th century, the albumen print was introduced by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard in 1850. A sheet of paper is coated with a mixture of albumen (egg whites), water, and ammonium or sodium chloride salt. The paper is floated on a bath of silver nitrate to form light-sensitive silver salt. The dried sheet is placed in direct contact with a negative in a printing frame and exposed to sunlight, whereupon the image forms spontaneously or “prints out.” In addition to fixing and washing, the print is usually toned with a gold solution to improve image stability and to change the hue from a reddish-brown to a purple-brown. Albumen prints can achieve rich, warm black tones and a high level of detail, with a surface sheen ranging from semigloss to a high gloss. However many albumen prints have faded and yellowed over time, losing detail and shifting their image hue toward sepia.

Carte-de-Visite

The carte-de-visite is a photographic format patented by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri in 1854. The image is created by making several exposures on the same negative in a specially designed camera with multiple lenses and a sliding plate holder. The resulting print, usually albumen, was then cut into multiple smaller prints of 2.5 by 4 inches that were usually mounted on cardstock.