Past Exhibition

Made in America: Radical Figures

Details

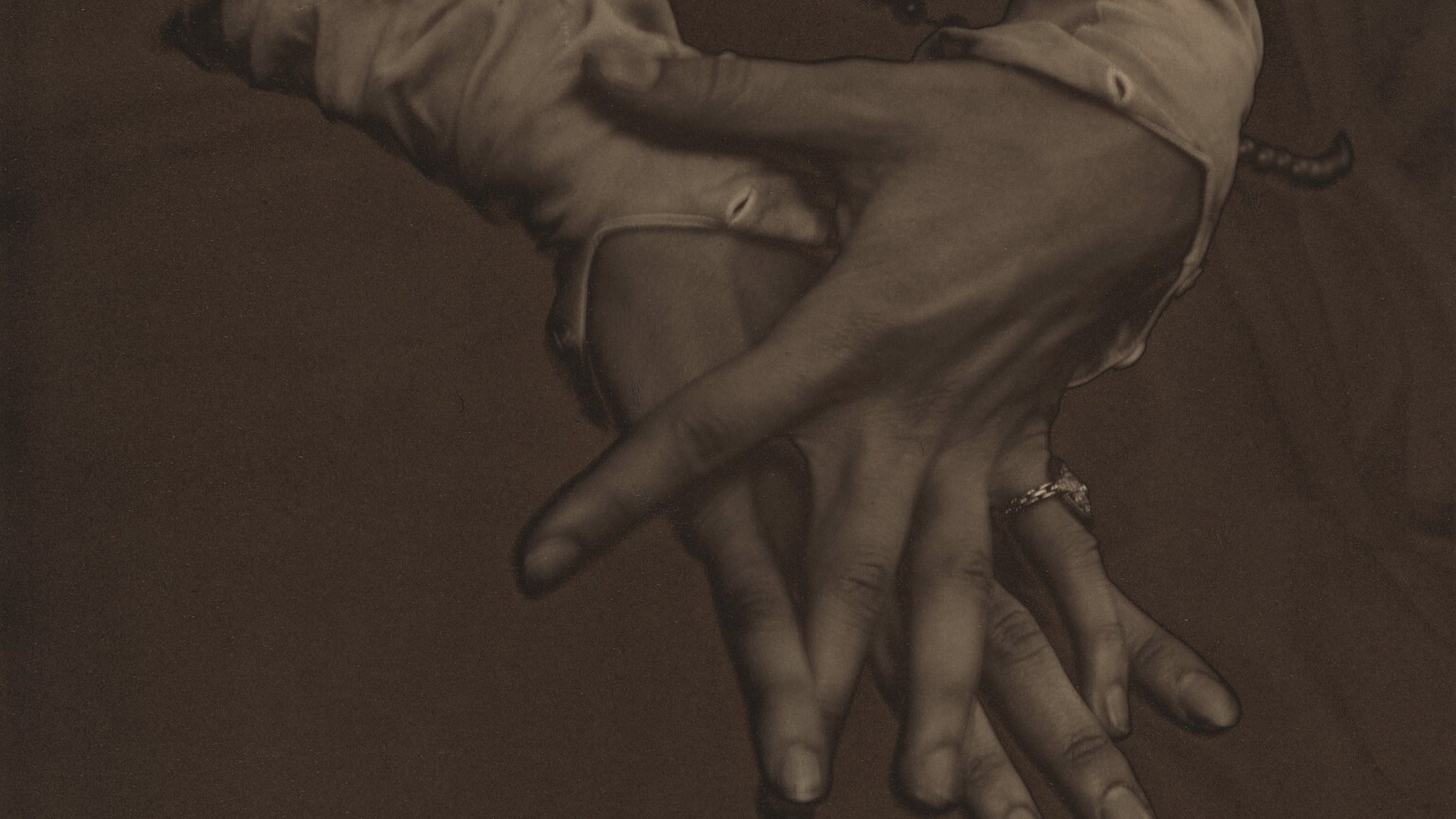

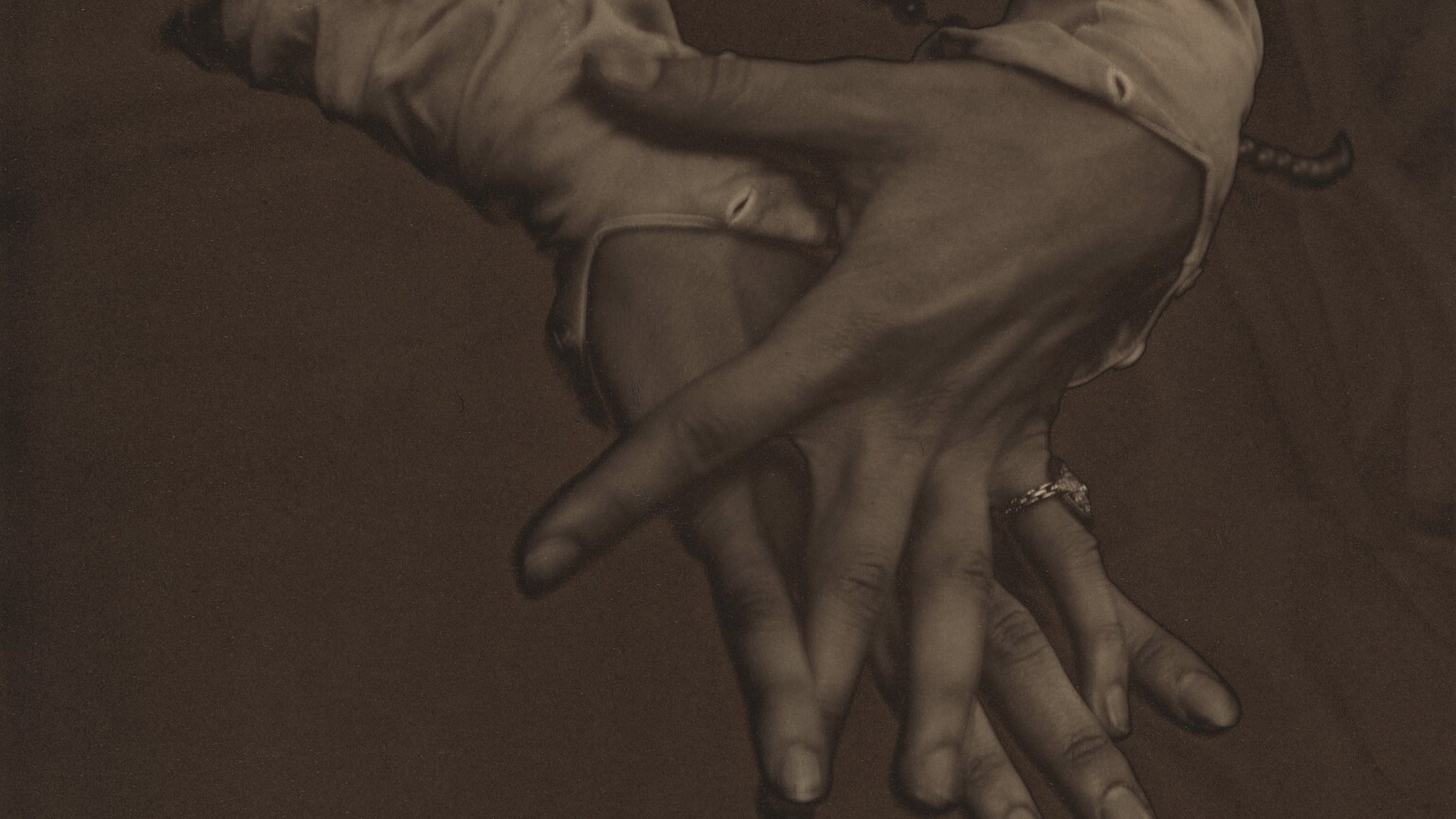

Alfred StieglitzAlfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery in New York City (1905–1917) was not much bigger than this installation’s room, but it sparked great debates about modern art. Pioneering exhibitions of work by such Europeans as Constantin Brancusi, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Rodin challenged Americans like Georgia O’Keeffe and Max Weber to reconceive the body in more expressive and abstract ways. In his photographs, Stieglitz explored how body parts—neck, torso, hands, legs, even feet—could convey the whole.

The art of the portrait was also rethought by the artists of 291, who played with words and symbols to express identity. Francis Picabia depicted Stieglitz as a broken machine—part camera, part car—with its limp bellows unable to reach the lens at the top. Marius de Zayas collaborated with Agnes E. Meyer, an art patron and journalist, to construct a fractured poem-portrait of a woman’s feelings about an illicit romance. Using colored triangles, Edward Steichen lampooned Marsden Hartley as Mushton Shlushley, the Lyric Poet and Aestheticurean (a fusion of “aesthete” and “epicurean”), and he depicted fellow painter John Marin as Johnny Marine, a beady-eyed peeping Tom.

O’Keeffe hesitated to show some of her paintings because she regarded them as intimate portraits, yet few viewers realized it: “They have slipped into the world as abstractions—no one seeing what they are.” Her 1946 painting A Black Bird with Snow-Covered Red Hills, with its mustachelike bird, may be a portrait of Stieglitz, who had a bushy mustache and referred to himself as Old Crow’s Feathers. If that is true, the painting can be read as O’Keeffe’s farewell to her husband, who had just died.

About this Series

American Art, 1900–1950: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs

During a period fueled by enormous urban growth and technological changes, riven by world wars, and rocked by new modes of thought, American artists explored many diverse means to express their changing experience and environment. Prints, drawings, and photographs were vital media through which artists pursued radical experiments in form, figuration, and abstraction. Reevaluating European traditions, they developed new ways of seeing the modern world around them.

Complementing the American modernist paintings and sculptures in the adjacent galleries, these rotating installations feature prints, drawings, and photographs by American artists working in the first half of the 20th century. By looking at pairs or groups of artists, or at broader themes such as abstract portraiture or the Machine Age, the installations spark conversations between established and lesser-known figures in American modernism and highlight the era’s full range and complexity.

Organization: Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington.