The Pre-Raphaelite Lens: British Photography and Painting, 1848–1875

Introduction

A few years after the discovery of photography was announced in 1839, the British art critic John Ruskin named it "the most marvelous invention of the century." Making permanent what the eye saw fleetingly, the new technology seemed an almost magical revelation.

As photography gained a foothold in the 1840s, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. These young painters and their followers wished to return to the purity, sincerity, and clarity of detail found in medieval and early Renaissance art that preceded Raphael (1483–1520). But they were also spurred on by the possibilities of the new medium, which could capture every nuance of nature. Indeed, Pre-Raphaelite artists painted with such precision that some critics accused them of copying photographs.

Many photographers in turn looked to the language of Pre-Raphaelite painting in an effort to establish their nascent medium as a fine art. Both photographers and painters—many of whom knew one another—drew inspiration directly from nature. In choosing subjects, they also mined literature, history, and religion, as well as modern life. Together they developed a shared vocabulary that is explored in this exhibition through the genres of landscape, narrative subjects, and portraiture.

John Everett Millais, British, 1829–1896, A Huguenot, on Saint Bartholomew's Day, Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge, 1851–1852, oil on canvas, The Makins Collection

Minute Details

The Pre-Raphaelites were inspired by the writings of critic John Ruskin, who became their advocate. Ruskin encouraged artists to paint directly from nature, "rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing." Heeding Ruskin's advice to observe nature closely, Pre-Raphaelite artists painted their landscapes out-of-doors. They filled every inch of the canvas with the minutiae of nature, precisely delineating vegetation and topography. Photographers, despite the challenges of working in the open air, were also drawn to nature, exploring the camera's ability to record sharp detail and building on the strong tradition of landscape painting in Britain.

Anstey's Cove depicts a site on the southwest coast of England, which Inchbold rendered with the sensitivity to detail recommended by Ruskin. The artist painted the far view of the cliff with the same meticulous focus as the near vegetation: this treatment evokes the sharp focus of photography rather than the perception of the human eye.

John William Inchbold, British, 1830–1888, Anstey's Cove, 1853–1854, oil on canvas, Lent by the Syndics of The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

White, who practiced law throughout his life, met with critical success as a landscape photographer in the mid-to-late 1850s. This subject was well suited to the collodion negative and albumen print process, which provided a level of detail and richness of tone that beautifully rendered an array of textures.

Henry White, British, 1819–1903, Ferns and Brambles, 1856, albumen print, Private collection

This watercolor is one of Ruskin's most highly finished nature studies. The close-up format was quickly adopted by photographers.

John Ruskin, British, 1819–1900, Rocks and Ferns in a Wood at Crossmount, Perthshire, 1847, pencil, ink, watercolor, and gouache on paper, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, Cumbria, England

Ruskin's admiration for photography's ability to capture precise detail led him to amass a large collection of daguerreotypes that were either purchased by him or taken by his valets Frederick Crawley and John Hobbs.

John Ruskin and attributed to John Hobbs, British, 1819–1900; dates unknown, Venice, Ducal Palace, Judgment Capital, c. 1849–1852, daguerreotype, Courtesy K. & J. Jacobson, UK

The light reflecting off the foliage in this bird's-eye view of a Scottish garden resembles a dusting of snow (a common effect in early landscape photographs). Drummond made his albumen prints with a variation called the malt process, which produced particularly rich purple tones.

Reverend David Thomas Kerr Drummond, Scottish, 1805–1877, Loch Earn, c. 1864, albumen print, Scottish National Photography Collection, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Here a photographer captured a scene in Ireland with a painter depicting the same site. Such interactions were not uncommon in these decades.

John Payne Jennings, British, 1843–1926, The Dargle Rock, c. 1869, albumen print, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

Natural Effects

Both photographers and Pre-Raphaelite painters spent hours outdoors working to record seasonal effects and changing light conditions. Photographers endeavored to achieve delicate atmospheric effects that mimicked the perception of the eye. However, they faced difficulties in capturing sky and earth together because photographic materials were more sensitive to blues than to greens and browns. Land, trees, and foliage therefore required longer exposure times than the sky. This problem often led photographers to compose views that minimized overexposed skies. Pre-Raphaelite painters in turn studiously observed the effects of sunlight on color, which led to a riot of brilliant hues in even the darkest shadows of their paintings. John Ruskin, responding to the common charge that the Pre-Raphaelites had no consistent formula for arranging light and shadow on their canvases, asserted that "their system...is exactly the same as the Sun's; which is, I believe, likely to outlast that of the Renaissance, however brilliant."

The difficulty of Wortley’s task—simultaneously recording different elements despite their various sensitivities to light—was noted by the press. By photographing only sea and sky, Wortley took advantage of the balancing effect of the light reflected on the water. In addition, he aimed his camera toward the sun while it was partially covered with clouds.

Colonel Henry Stuart Wortley, British, 1832–1890, The Clouds Are Broken in the Sky, c. 1863, albumen print, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In Mid-Spring, Inchbold adopted a composition that is essentially photographic: sun-dappled bluebells fill the bottom of the picture while trees are sliced off at the top. Photographers often used such a low vantage point, as is seen in Charles Conway's Winter. The resultant cropping mirrored the fragmentary character of human sight and avoided vast expanses of sky, which would appear as a blank white area because of the sensitivity of photographic chemicals to the blue end of the light spectrum.

John William Inchbold, British, 1830–1888, Mid-Spring, c. 1856, oil on panel, Private collection

Charles Conway, British, active 1850s, Winter, 1855, albumen print, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1963

John William Inchbold, British, 1830–1888, The Chapel, Bolton, 1853, oil on canvas, Northampton Museum and Art Gallery

The Gothic ruins of Bolton Abbey in northern England attracted nineteenth-century painters and photographers alike. Taken a year after Inchbold completed his painstaking painting of the subject, Fenton's photograph explores a softer, more atmospheric treatment. Fenton, like Inchbold, avoided the view of the priory from the nearby river, which earlier artists such as J.M.W. Turner had made famous. Fenton instead focused on the play of light and shadow on the abbey's façade, including the light filtering through the Gothic tracery of the window.

Roger Fenton, British, 1819–1869, Bolton Abbey, West Window, 1854, albumen print, The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Media Museum, Bradford. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund

A Scottish earl who earned patents for several scientific inventions, Caithness took up landscape photography as an amateur and exhibited his work at various photographic societies. In this photograph forceful juxtapositions of light and dark capture the effect of bare winter trees dusted in snow.

Earl of Caithness, Scottish, 1821–1881, Avenue at Weston, Warwickshire, 1860s, albumen print, Courtesy of George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

Delamotte, the son of a painter and lithographer, framed the brightly illuminated river with trees and their reflections, and thus created a study of light and dark tones.

Philip Henry Delamotte, British, 1821–1889, Evening, 1854, albumen print, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1952

Portraits & Studies

The Pre-Raphaelite circle was a lively mix of painters, photographers, and writers. At the illustrious gatherings hosted by family of the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron in London, guests included the painters William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and George Frederic Watts. Cameron also invited guests to her home on the Isle of Wight, where they might have been introduced to her neighbors, Alfred Tennyson and his family. One visitor was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). An enthusiastic follower of the visual arts, he also became a talented photographer who focused almost exclusively on making portraits. Although immediately hailed for its ability to record true likenesses, photography was criticized for failing to capture the liveliness and subtleties of human expression, a result of the long exposure times then necessary. Photographers such as Cameron and David Wilkie Wynfield responded by manipulating focus and experimenting with pose, costume, and setting to achieve compelling portraits.

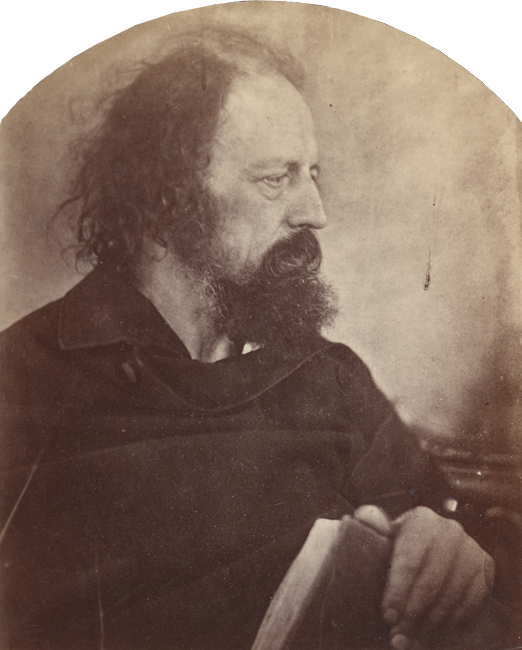

One of Cameron's several portraits of Tennyson, the above print presents him as the model of a Romantic poet, disheveled and wearing a cloak. "I prefer," he wrote, "the Dirty Monk to the others of me."

Julia Margaret Cameron, British, 1815–1879, Alfred Tennyson (The Dirty Monk), 1865, albumen print, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1966

After training in Italy in the 1840s, Watts produced many portraits, literary and history paintings, and murals. Here, he painted a lyrical portrait of his wife, the actress Ellen Terry, wearing her wedding dress, a Renaissance-inspired gown designed by William Holman Hunt. She lifts showy camellias to her face, crumpling the modest but more sweetly scented violets in her hand. Terry acted as muse to both Julia Margaret Cameron and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll).

George Frederic Watts, British, 1817–1904, Choosing, 1864, oil on strawboard, Lent by the National Portrait Gallery, London

Dodgson saw and admired George Frederic Watts' portrait of Ellen Terry, Choosing, at the Royal Academy in 1864. The following year, Dodgson photographed Terry in the same dress, her wedding gown, at her family home. She had recently separated from the much older Watts, whom she had wed at the age of sixteen (the marriage lasted only a year).

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, British, 1832–1898, Mrs. Watts (Fancy Dress), 1865, albumen print, Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Jane Burden, the daughter of a stableman, was attending a theatrical performance in Oxford when she met Rossetti, who convinced her to model for him. She married the designer William Morris in 1859 and later resumed modeling for Rossetti, who painted her repeatedly from 1868 to 1882. Rossetti, who was passionately involved with Jane during this time, usually transformed her into mythological and literary heroines in his paintings. Here, however, he presented his muse as herself, wearing a gown he helped her design. She appears in a similar dress and pose in several photographs by John Robert Parsons.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, British, 1828–1882, Jane Morris (The Blue Silk Dress), 1868, oil on canvas, By Permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London

In the summer of 1865 Rossetti invited Parsons to his home to photograph his model Jane Morris. Parsons, a painter who had recently taken up photography, operated the camera, but Rossetti staged the photographs, working with Morris to adjust her hair, posture, attire, and background. A series of eighteen photographs resulted. Rossetti used them as inspiration for his oil paintings of Morris, including The Blue Silk Dress.

John Robert Parsons, British, c. 1825–1909, Jane Morris, 1865, albumen print, Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Hunt's attire is not a historical costume, but an outfit he took to wearing after his travels to the Middle East.

David Wilkie Wynfield, British, 1837–1887, William Holman Hunt, early 1860s, albumen print, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A mathematics don at Oxford whose pen name was Lewis Carroll, Dodgson often photographed the children of acquaintances. Amy was the daughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter and illustrator Arthur Hughes.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, British, 1832–1898, Amy Hughes, 1863, albumen print, Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Poetic Subjects

A hallmark of the Pre-Raphaelite style was a preference for poetic subjects drawn from literature, history, religion, and mythology. Shakespearean plays, poems by Alfred Tennyson, and tales from King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table were particular favorites. Pre-Raphaelite artists focused on intimate, emotional moments and strove for historical accuracy by carefully researching period costumes and settings. Photographers, too, turned to these sources, staging scenes in an effort to demonstrate that photography could equal painting in narrative potential.

The story of Elaine, a tragic tale of unrequited love, was told by Sir Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur (1485) and reworked by Tennyson in Idylls of the King. Lancelot has left his shield in Elaine's care while he competes in a tournament with a blank shield to disguise his identity. She eventually dies of a broken heart, and, at her request, her body is borne by boat to Camelot.

Henry Peach Robinson, British, 1830 – 1901, Elaine Watching the Shield of Lancelot, 1862, albumen print, The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Media Museum, Bradford. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund

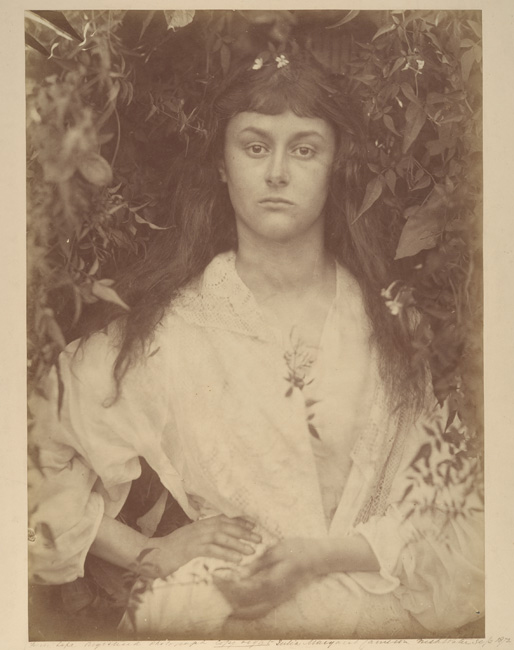

Cameron's distinctive large-scale images of single female figures in a shallow space evoke Rossetti's poetic paintings of women. To illustrate the Roman goddess of fruitfulness, Cameron placed the model Alice Liddell against flowering vines and allowed her hair to blend into the leaves. As a young girl, Liddell had been Lewis Carroll's muse for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

Julia Margaret Cameron, British, 1815–1879, Pomona, 1872, albumen print, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1963

Music makes a frequent appearance in Pre-Raphaelite paintings, complementing delights for the eye with pleasures for the ear. Highly ornamented works such as this one derive from Rossetti's passion for medieval manuscript illumination, though the musical instruments shown here are purely imaginary. The designer and poet William Morris purchased this vibrant watercolor. It inspired him to write a poem of the same name, which begins "Lady Alice, Lady Louise, / Between the wash of the tumbling seas / We are ready to sing, if so ye please: / So lay your long hands on the keys...."

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, British, 1828–1882, The Blue Closet, 1857, watercolor on paper, Tate: Purchased with assistance from Sir Arthur Du Cros Bt and Sir Otto Beit KCMG through The Art Fund 1916

Rossetti's influence on Cameron's photographs is evident in both their subject matter and composition. The musical subject and medieval look of this photograph also characterize Rossetti's watercolor The Blue Closet.

Julia Margaret Cameron, British, 1815–1879, A Minstrel Group, 1866, albumen print, Collection of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro

A curse befell the Lady of Shalott, who glides down the river to Camelot, where she will die. Based on an Arthurian legend, as retold by Tennyson, Robinson's work is a tour de force made from more than one negative. One reviewer noted that it reflected “the quaint poetic manner of the Pre-Raphaelites.”

Henry Peach Robinson, British, 1830–1901, The Lady of Shalott, 1860, albumen print, Tunbridge Wells Museum & Art Gallery

In illustrating Shakespeare's tragedy, Cameron closely framed the four characters and focused on the psychological intensity of their expressions. Lear has announced that he will divide his kingdom among his daughters, giving the largest allotment to the one who loves him best. Charles Cameron, the photographer's husband, modeled for King Lear, while the three Liddell sisters posed as his daughters, with Alice at right. Lewis Carroll's muse for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, she also appears as Pomona.

Julia Margaret Cameron, British, 1815–1879, King Lear Allotting His Kingdom to His Three Daughters, 1872, albumen print, Courtesy of George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

Romance & Modern Life

Telling stories was an important function of the visual arts throughout the era of Queen Victoria (reign 1837–1901). Pre-Raphaelite narratives often dwell on love and romance, from depictions of the joys of courtship to its perils, played out in scenes of yearning and unrequited passion. Painters communicated poignant situations and heightened emotions through pose and expression. Photographers sought to achieve the same effects in evocative, staged vignettes and occasionally addressed grimmer aspects of modern life. Some of these photographs do not relate to specific literary sources, but recall the narrative scenes and intimate moods found in Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Often, the title sets the tone and alerts the viewer to the implied story.

Frederick Pickersgill, British, 1820–1900, Sunshine and Shade, 1859, from The Sunbeam: A Photographic Magazine (London, 1857–1861), albumen print, The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Media Museum, Bradford. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund

The tragic romance between the son of a squire and Maud, the daughter of a woodsman, is chronicled in a poem by Millais' friend Coventry Patmore. Here Millais depicted the future lovers as childhood friends. The young boy tempts the girl with strawberries, foreshadowing later events, as her father works behind them. The story ends with Maud's ruin: she goes mad after drowning their illegitimate child. Fulfilling the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites, Millais painted the background details directly from nature.

John Everett Millais, British, 1829–1896, The Woodman's Daughter, 1850–1851, oil on canvas, Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

This preliminary study for Fading Away, a print made from multiple negatives, takes its title from Shakespeare's Twelfth Night.

Henry Peach Robinson, British, 1830 - 1901, She Never Told Her Love, 1857, albumen print from a wet collodion negative, Paul Mellon Fund, 2007.29.40

Robinson, who had initially trained as a painter, was known for combining multiple negatives to create complex compositions. This photograph provoked controversy when first exhibited: though praised for conveying the family's anxiety as the consumptive child lies dying, it was also criticized for making such an upsetting subject seem too realistic.

Henry Peach Robinson, British, 1830–1901, Fading Away, 1858, albumen print, The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Media Museum, Bradford. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund

Drawn from Tennyson's poem The Gardener's Daughter (1842), this photograph illustrates the title character, Rose. The narrator, an artist, falls in love when he happens upon her trying to reattach a fallen rose: "Gown'd in pure white, that fitted to the shape— / Holding the bush, to fix it back, she stood. / A single stream of all her soft brown hair / Pour'd on one side.…"

Julia Margaret Cameron, British, 1815–1879, The Gardener's Daughter, 1867, albumen print, National Media Museum Collection, Bradford

One of several small paintings of single figures of women painted by Millais in the 1850s, Waiting demonstrates the shift in his work away from the dense narratives of such paintings as The Woodman's Daughter toward more open-ended subjects that suggest rather than tell the story.

John Everett Millais, British, 1829–1896, Waiting, 1854, oil on mahogany, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. Gift from Mrs. Edward Nettlefold, 1909