Tell It with Pride: The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial

Even before the war’s end in April 1865, the courage and sacrifice that the 54th Massachusetts demonstrated at Fort Wagner inspired artists to commemorate their bravery. Two artists working in Boston, Edward Bannister and Edmonia Lewis, were among the first to pay homage to the 54th in works they contributed to a fair that benefited African American soldiers. Yet it was not until the late 19th century that Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial solidified the 54th as an icon of the Civil War in the American consciousness.

Commissioned by a group of private citizens, Saint-Gaudens first conceived the memorial as a single equestrian statue of Colonel Shaw, following a long tradition of military monuments. Shaw’s family, however, uncomfortable with the portrayal of their 25-year-old son in a fashion typically reserved for generals, urged Saint-Gaudens to rework his design. The sculptor revised his sketch to honor both the regiment’s famed hero and the soldiers he commanded—a revolutionary conception at the time. Saint-Gaudens worked on his memorial for 14 years, producing a plaster and a bronze version.

When the bronze was dedicated on Boston Common on Memorial Day 1897, Booker T. Washington declared that the monument stood “for effort, not victory complete.” After inaugurating the Boston memorial, Saint-Gaudens continued to modify the plaster, reworking the horse, the faces of the soldiers, and the appearance of the angel above them. The success of his final plaster earned the artist the grand prize for sculpture when it was shown at the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris. It was installed at the National Gallery of Art in 1997, on long-term loan from the U.S. Department of the Interior, the National Park Service, and the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, New Hampshire.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), Shaw Memorial, 1900, patinated plaster, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, Cornish, New Hampshire, on long-term loan to the National Gallery of Art, Washington

Many African Americans offered to fight for the Union cause at the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, but it was not until President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, that they were legally allowed to enlist. Immediately thereafter Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew started to form the first African American regiment in the North, the 54th Massachusetts and appointed Robert Gould Shaw as its colonel. With the abolitionist George Luther Stearns the governor formed the “Black Committee” of prominent citizens, both black and white—including Frederick Douglass, shown here, William Lloyd Garrison, Amos A. Lawrence, and Wendell Phillips—to garner support for the regiment. These men, along with other leaders of the African American cause, canvassed the country seeking soldiers for the 54th. They urged men to recognize, as Douglass persuasively argued, that those “who would be free themselves must strike the first blow.”

A noted social reformer, orator, statesman, and writer, Douglass became a leading protagonist in the abolitionist movement after escaping from slavery in eastern Maryland in 1838. In this photograph he revealed himself to be, as the abolitionist and suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton noted, “majestic in his wrath.”

Samuel J. Miller (1822–1888), Frederick Douglass, c. 1847–1852, daguerreotype, Art Institute of Chicago, Major Acquisitions Centennial Endowment

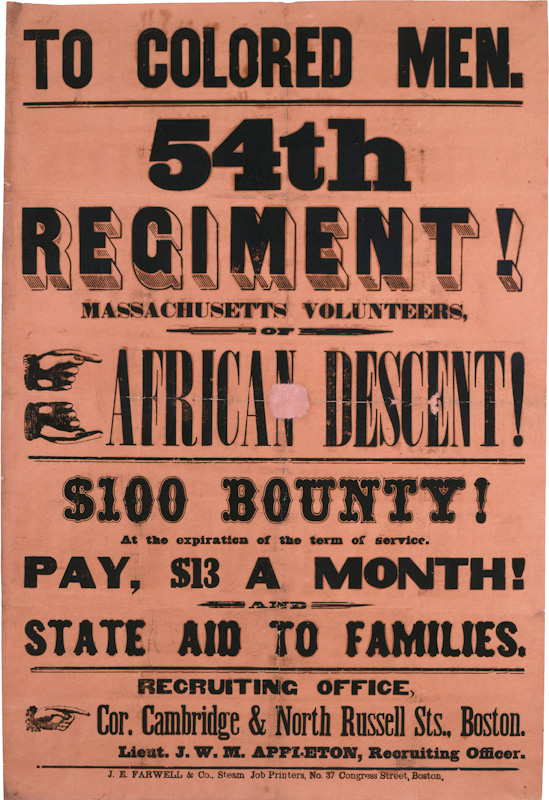

J. E. Farwell and Co., To Colored Men. 54th Regiment! Massachusetts Volunteers, of African Descent, 1863, ink on paper, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Beginning in March 1863, African American recruits streamed into Camp Meigs on the outskirts of Boston, eager to enlist in the 54th. By May, the regiment numbered more than 1,000 soldiers. Most were freemen working as farmers or laborers; some were runaway slaves. Many of the new enlistees, proud of their professions and uniforms, had photographs of themselves taken. Their pictures recall Frederick Douglass’ 1863 speech before an audience of potential recruits: “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on the earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.”

Henry F. Steward, shown here, actively recruited for the 54th in Michigan. He had been promoted to sergeant soon after he arrived at Camp Meigs and probably had this portrait made shortly after he received his rifle and uniform. Proud of his new career, Stewart paid an extra fee to have the photographer tint his cap, sword, breastplate, and pants with paint to highlight their importance. Steward survived the Battle of Fort Wagner but died just over two months later, most likely of dysentery.

Sergeant Henry F. Steward, 1863, ambrotype, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew, seeking to ensure that Robert Gould Shaw would accept command of the regiment, wrote to Shaw’s abolitionist father, “This I cannot but regard as perhaps the most important corps to be organized during the whole war.” Though initially hesitant, the 25-year-old Shaw accepted Andrew’s offer and was appointed colonel.

Mathew B. Brady (1823–1896), Governor John A. Andrew, c. 1861–1866, albumen print, Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS, Am 1084 (59), Gift, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Commandery of the State of Massachusetts, 1974

Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew appointed 25-year-old Robert Gould Shaw as colonel of the 54th, promoting him several grades above his previous rank of captain of the 2nd Massachusetts. Shaw and his second-in-command, lieutenant colonel Norwood Penrose Hallowell, evaluated the other officers, all of whom, by military regulations of the time, had to be white. Many of the officers came from strong abolitionist families and almost all had previous service in other Union regiments. Some of the officers, like Shaw, had their portraits made as small carte de visite photographs that were inexpensive and could be easily sent through the mail.

When orders came for the 54th to assist several all-white regiments in the attack on Fort Wagner, Shaw was determined to prove that they were fit soldiers. Fort Wagner was among several forts that guarded Charleston, South Carolina. As explosions lit up the night sky, Shaw led the 54th into the fray. When they were about 150 yards from the fort, Confederate troops opened fire. The 54th reached the parapet, but after a violent struggle, they were forced to retreat. Of the 600 soldiers from the regiment who participated in the assault, more than 280 were killed, wounded, captured, or missing and presumed dead. Shaw was among those killed in action. Although defeated in combat, the 54th forever distinguished itself. “Wagner was the battle-ground, not of regiments,” one newspaper wrote,”but of centuries and civilizations, and the black man there won his place among the freemen of the age and wiped out the stain of servitude.”

John Adams Whipple (1822–1891), Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, 1863, albumen print, Boston Athenaeum

Purvis, the son of a free woman of color and a wealthy white cotton broker from Charleston, South Carolina, was an ardent abolitionist and women’s rights activist.

Robert Purvis, c. 1840–1848, daguerreotype, Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

Women, such as the former slave, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth, who solicited recruits in Michigan, provided critical support for the 54th Massachusetts. Her grandson, James Caldwell, served as a private in the regiment.

Sojourner Truth, 1864, albumen print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Image: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY

On July 20, 1863, two days after the Union assault on Fort Wagner, Lewis Douglass, son of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, wrote to his fiancée, recounting the bravery of his comrades: “We charged that terrible battery on Morris Island known as Fort Wagner.… I escaped unhurt from amidst that perfect hail of shot and shell. It was terrible…. The regiment has established its reputation as a fighting regiment, not a man flinched, though it was a trying time…. I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops—we would put an end to this war.”

Case and Getchell, Sergeant Major Lewis H. Douglass, 1863, albumen print, Frederick Douglass Collection, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

A sailor born in Toronto, Canada, Abraham Brown accidentally killed himself while cleaning his gun on July 11, 1863, on James Island, northwest of Fort Wagner.

Private Abraham F. Brown, 1863, tintype, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Born in New Orleans, Gooseberry had worked as a sailor in St. Catharines, Ontario, before he enlisted in the 54th on July 16, 1863. He survived the war but died destitute at about age 38.

Private John Gooseberry, musician, 1864, tintype, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Colonel Shaw referred to Private Alexander Johnson, a 16-year-old recruit from New Bedford, Massachusetts, as the “original drummer boy.” He was with Shaw when the colonel died at Fort Wagner and carried important messages to other officers during the battle.

H. C. Foster (?), Private Alexander H. Johnson, musician, 1864, tintype, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

John Wilson, a painter from Cincinnati, Ohio, had this portrait made a month after he was promoted to sergeant major in May 1864. One of only five African American noncommissioned officers in the regiment at the time, Wilson proudly displayed his stripes and cap with its horn and the number “54.”

Sergeant Major John Wilson, June 3, 1864, albumen print, West Virginia University Libraries, West Virginia and Regional History Collection

After appointing Robert Gould Shaw to be the colonel of the 54th, Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew named Norwood Penrose Hallowell, son of abolitionists in Philadelphia, as lieutenant colonel.

Captain Norwood P. Hallowell, c. 1862–1863, albumen print, Pamplin Historical Park and The National Museum of the Civil War Soldier. Image courtesy of Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the the Civil War Soldier

Major Lincoln R. Stone, the surgeon for the regiment, had this photograph made on the day that the 54th marched through Boston on its way to sail for combat in the South.

Major Lincoln R. Stone, surgeon, May 28, 1863, albumen print, Pamplin Historical Park and The National Museum of the Civil War Soldier. Image courtesy of Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the the Civil War Soldier

Luis Emilio, the son of a Spanish immigrant and pictured in the center of this photograph, enlisted in the Union army in 1861 at age 16 (even though the minimum age was 18). When he mustered out at the war’s end, he was only 21. He later wrote the first history of the 54th Massachusetts.

Second Lieutenant Ezekiel G. Tomlinson, Captain Luis F. Emilio, and Second Lieutenant Daniel Spear, October 12, 1863, tintype, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Currier & Ives, The Gallant Charge of the 54th Massachusetts (colored) Regiment: On the Rebel Works at Fort Wagner, Morris Island, near Charleston, July 18th, 1863, and Death of Colonel Robt. G. Shaw, 1863, hand-colored lithograph, Boston Athenaeum, Gift of Raymond Wilkins, 1944

While many members of the 54th Massachusetts died on the battlefield, others survived thanks to the support of doctors, nurses, and caregivers. Susie King Taylor, shown here, tended soldiers’ wounds on Morris Island.

Susie King Taylor, nurse, 1902, halftone frontispiece from Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, Chris Foard

By the war’s end in 1865, years of bombardment had reduced the once cosmopolitan Charleston to “a city of the dead.” Amid the destruction, Charleston’s African Americans came together on May 1, 1865, to commemorate the nation’s losses in a ceremony that is now known as Memorial Day. Among those who returned to Charleston to honor the fallen were members of the 54th Massachusetts.

In 1866, with the endorsement of Major General William T. Sherman, George N. Barnard published a volume of photographs documenting the scarred battlefields, ruined buildings, and burned landscapes that the war left in its wake. The book concludes with his elegiac depictions of Charleston.

This photograph shows a white man—perhaps Barnard’s assistant—and a younger black man contemplating the destruction around them, with the hint of renewal on the horizon.

George N. Barnard (1819–1902), Ruins in Charleston, South Carolina, 1865 or 1866, albumen print from the album “Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign” (1866), Collection of the Sack Photographic Trust for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, fractional gift to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

As Colonel Shaw led the assault on Fort Wagner, a 23-year-old sergeant from New Bedford, Massachusetts, William H. Carney, was standing near him. When Sergeant Carney saw the color bearer drop the national flag, he recalled years later, “as quick as a thought, I threw away my gun, seized the colors and made my way to the head of the column.” As Shaw and Carney reached the top of the parapet, Shaw waved his sword, shouted “Forward, 54th!” and fell dead. The severely wounded Carney planted the flag and, when the order to retreat came, he extracted “the precious colors,” limped back to his comrades, and proclaimed: “Boys, I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground.”

Carney’s heroism at Fort Wagner earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor, making him the first African American to merit the nation’s highest award for bravery. Yet due to an administrative oversight, he did not receive his medal until May 1900. To commemorate his achievement, Carney had his photograph taken by James E. Reed—one of the few African American photographers at the time to own and operate a photography studio in Massachusetts—while proudly wearing his Medal of Honor.

The inscription on the back of the medal reads: “The Congress to Sergeant William H. Carney, Co. C. 54th Mass Inf., for gallantry at Fort Wagner, S.C., July 18, 1863.”

James E. Reed (1864–1939), William H. Carney, c. 1901–1908, gelatin silver print, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

Congressional Medal of Honor, awarded to William H. Carney, July 18, 1863, designed by Christian Schussel, engraved by Anthony C. Pacquot, issued 1900, bronze and silk, Carl J. Cruz Collection

For over a century, the 54th Massachusetts, its famous battle at Fort Wagner, and the Shaw Memorial have remained compelling subjects for artists. Poets such as Paul Laurence Dunbar and Robert Lowell praised the bravery of these soldiers, as did composer Charles Ives. Artists as diverse as Lewis Hine, Richard Benson, Carrie Mae Weems, and William Earle Williams have highlighted the importance of the 54th as a symbol of racial pride, personal sacrifice, and national resilience. These artists’ works illuminate the enduring legacy of the 54th Massachusetts in the American imagination and serve as a reminder, as Ralph Ellison wrote in an introduction to Invisible Man, “that war could, with art, be transformed into something deeper and more meaningful than its surface violence.”

Around 1920 Hine traveled to Atlanta to document local African American communities. His series, “Southern Negroes,” included this photograph of a couple reading to their daughters. Above the mantelpiece hangs a Curtis & Cameron print of the Shaw Memorial.

Lewis Hine (1874–1940), Black Family by Fireplace, from the series “Southern Negroes,” c. 1920, gelatin silver print, Collection of George Eastman House, Transfer from Photo League Lewis Hine Memorial Committee; ex-collection of Corydon Hine

In 1973 Richard Benson and Lincoln Kirstein published Lay This Laurel, a book with photographs by Benson, an essay by Kirstein, and poems and writings by Emily Dickinson, Frederick Douglass, and Walt Whitman, among others. It was intended to focus renewed attention on the bronze version of the Shaw Memorial on Boston Common, which had fallen into disrepair.

Richard Benson (born 1943), Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, 1973, pigmented ink jet print, Gift of Susan and Peter MacGill. © Richard Benson, Courtesy of Pace MacGill Gallery, New York

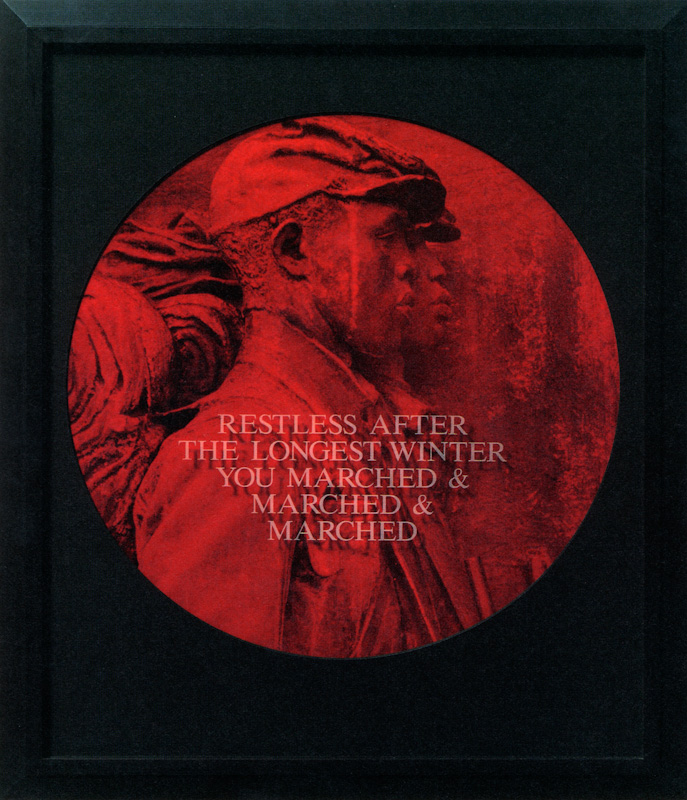

In this piece Carrie Mae Weems appropriated and altered one of Richard Benson’s photographs of the Shaw Memorial. Printed with a blood red filter, it is placed beneath glass etched with words that allude to African Americans’ quest for freedom and equal rights as well as their long struggle to attain them.

Carrie Mae Weems (born 1953), Restless After the Longest Winter You Marched & Marched & Marched, from the series “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” 1995–1996, chromogenic color print with etched text on glass. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Carrie Mae Weems

This photograph is part of William Earle Williams’ series “Unsung Heroes: African American Soldiers in the Civil War,” depicting locations where black troops served, fought, and died. This picture records the location where Fort Wagner once stood; it is now submerged, marked only by the lighthouse.

William Earle Williams (born 1950), Folly Beach looking towards Morris Island, 1999, 1999, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Purchased as the Gift of the Gallery Girls