Henry Moore

Introduction

Henry Moore (1898-1986) was one of the twentieth century's great sculptors. First emerging from the relative obscurity of the radical modernist movement in England in the 1920s, Moore quickly established himself as one of Britain's leading young artists. In 1946 his sculpture was presented in a one-man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Two years later, he won the prestigious International Prize at the Venice Biennale. After 1950, with the sponsorship of the British Council (an organization promoting British cultural values), Moore executed large-scale public projects throughout the Western world. At the time of his death, Moore was a formidable cultural presence whose work had become synonymous with modern sculpture.

This exhibition is the first U.S. retrospective in twenty years to assess Moore's contributions to the art of the last century. At once an homage and a voyage of rediscovery, the show traces the crucial stages of the artist's development: from his groundbreaking work following World War I and his experimentation with abstraction and surrealism in the 1930s, to his patriotic engagement as an official war artist during World War II, his postwar humanism, and his interest in large-scale public sculpture during the last four decades of his life. Presenting both sculpture and drawings, the exhibition examines the development of Moore's formal and thematic repertoire, his enduring preoccupation with the reclining figure, and his radical exploration of sculptural form.

Henry Moore, Family Group, 1948-1949, bronze, Tate, London, Purchased 1950

Carving a Reputation: The 1920s

Henry Moore was born and raised in Yorkshire, a rugged mining region in northern England. After serving in the trenches of World War I, he studied and then taught at the Royal College of Art in London--a stronghold of academic formalism that afforded students few opportunities to explore nontraditional sources for their art. His chance discovery of Roger Fry's seminal book Vision and Design in 1921, with essays on African and pre-Columbian art, led Moore to the British Museum, where he found inspiration in its vast collections of non-European art. The art of ancient Mexico particularly appealed to him: "Its 'stoniness,' by which I mean its truth to material,...its approach to a full-dimensional conception of form, make it unsurpassed in my opinion by any other period of stone sculpture."

The encounter with the bold forms of non-Western art liberated the young artist from the constraints of the neoclassical tradition. His sculpture from the 1920s was, for the most part, intimately scaled work created in response to the sensuous colors and textures of wood and stone. He favored native British materials, such as Hornton stone and English elm, over traditional Italian marbles. During a visit to Paris in 1923 he saw the work of contemporary sculptors, including Constantin Brancusi, whose radical reduction of the human figure and understanding of sculpture in the round defined the path of his art. At home in London, Moore was most deeply affected by the works of the French expatriate Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and by the American sculptor Jacob Epstein, who fostered the young man's penchant for tribal art and bold formal expression.

Both Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska passionately advocated the art of "direct carving." Deeply convinced of the sculptor's symbiotic relationship with his or her craft, they shunned preliminary techniques such as pointing-up (which translated the proportions of a small model to a larger scale), seeking instead to release their forms directly from within their materials. "A sculptor," Moore noted, "gets the solid shape, as it were, inside his head--he thinks of it, whatever its size, as if he were holding it completely enclosed in the hollow of his hand. He mentally visualizes a complex form all around itself; he identifies himself with its center of gravity, its mass, its weight; he realizes its volume, as the space that the shape displaces in air."

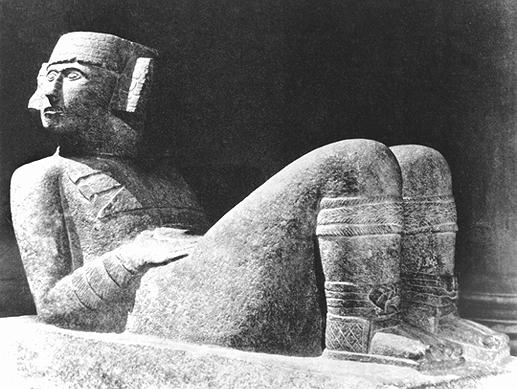

Aztec Chocmool figure, 900-1000 A.D., Mexico, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City

In 1928 Moore's first solo exhibition in London won him favorable reviews and a lifelong friend, the influential critic Herbert Read. That same year, Moore created his first masterpiece, a reclining figure, touching upon a theme he would revisit many times. The work was inspired by a photograph of a pre-Columbian carving of the rain spirit Chacmool that Moore had discovered in a 1922 book on Mexican art. The horizontal, earthbound pose of both the Chacmool and of Moore's Reclining Woman powerfully suggests connections with landscape, an idea that would preoccupy him throughout his creative life.

Henry Moore, Reclining Woman, 1930, Hornton stone, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Purchased 1956

Abstraction and Surrealism: The 1930s

The 1930s represent Moore's most radical and inventive phase. Building on his interest in non-European art and the avant-garde sculpture of Brancusi and Epstein, Moore pushed his art into new territory. During regular trips to Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s, he met Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Picasso, André Breton, and others working in the surrealist vein. Their interest in the workings of the unconscious, in what lay beyond the constraints of logic and reason, opened up new avenues of formal expression for Moore. He now exhibited in surrealist circles in London, Paris, and New York. "Beauty, in the later Greek or Roman sense," he noted, "is not the aim of my sculpture."

Henry Moore, Girl, 1931, Ancaster stone, Tate, London, Purchased 1952

Figurative work increasingly gave way to more abstract forms. The sculpture that moved Moore most was strong, self-supporting, and fully realized in three dimensions, "giving off something of the energy of great mountains," he observed. In formal and thematic terms Moore's work remained a synthesis--the product of keen observation and intellect wound around a core of personal experience and private obsession. His creative process was driven by the assimilation of disparate visual ideas. He collected stones, twigs, bones, and shells, using them as creative points of departure. He pierced volumes with holes, tunneling out heavy masses to explore form within form. As seen in Reclining Figure, Moore was also interested in the creative tensions between figuration and abstraction, working in a style the poet and critic Geoffrey Grigson in 1935 called "biomorphism." Good art, Moore asserted, contains elements both abstract and surrealist, classical and romantic: "Order and surprise, intellect and imagination, conscious and unconscious. Both sides of the artist's personality must play their part."

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure, 1939, elmwood, The Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase with funds from the Dexter M. Ferry, Jr. Trustee Corporation

In the late 1930s, geometric elements entered his work. Sculptures such as Stringed Figure were inspired by mathematical models Moore had seen at the Science Museum in London. Indebted to surrealism's play with ambiguity and transformation, his stringed sculptures allowed Moore to play linearity against mass, color against material. Such play was key to another recurrent theme: the interactions of internal and external forms.

Henry Moore, Stringed Figure, 1937, cherry wood and string on oak base, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase Fund, 1989

Crisis and Aftermath: The 1940s and 1950s

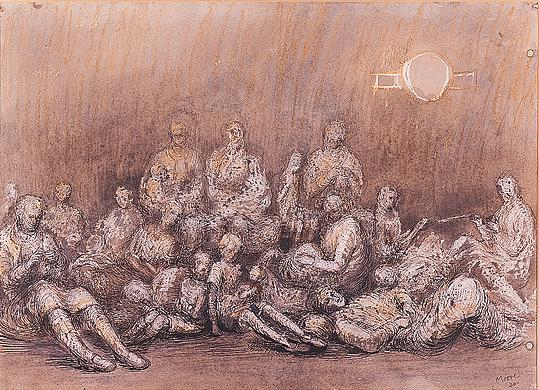

During the war years, when materials were scarce and opportunities rare, Moore found it impossible to execute major sculptural projects. Increasingly conscious of the war's devastating effect, he began to sketch Londoners seeking shelter in the Underground Railway during the German air raids of 1940. His drawings, powerful evocations of human suffering in gouache and ink, proved exceptionally popular with British audiences, boosting Moore's reputation.

Henry Moore, Grey Tube Shelter, 1940, pen and ink, chalk, wash, and gouache on paper, Tate, London, Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946

In 1940, Kenneth Clark, a mentor, appointed Moore an official war artist, a salaried position in the British government. He commissioned Moore to make drawings of coal miners at Wheldale Colliery in Castleford, a mining pit once managed by Moore's father. Moore thus continued his investigations into the dark subterranean worlds that had intrigued him in London, documenting "carvers" of a very different kind.

Henry Moore, Miner at Work, 1942, ink, chalk, and gouache on paper, Imperial War Museum, London

Later that year, after his old studio in Hampstead was bombed, Moore moved north of London to the small village of Much Hadham. His work softened, reflecting Moore's deepened interest in human relationships and connections with the natural environment. In 1946, his only child Mary was born, leading to a series of works evoking family life. At the same time, his career reached new heights as the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited his work in a major retrospective. Following the horrors and destruction of World War II, Moore's wholesome and universal imagery suggested spiritual rebirth and found widespread approval.

After the war, Moore briefly ventured into darker thematic territory, confronting demons both private and public. The emaciated body of Warrior with Shield, for example, is precariously perched on a plinth, his amputated limbs piercing the air like a silent scream, his head gashed.

Henry Moore, Warrior with Shield, 1953-1954, bronze, The Moore Danowski Trust

In a dark and shocking variation on the mother and child theme, Moore depicted a spindly, birdlike child sharply attacking her mother's breast. The brutality of their encounter is matched only by the rough, tortuous quality of the sculpture's metal surface.

Henry Moore, Maquette for Mother and Child, 1952, bronze, The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of Irina Moore 1977

Embracing Greatness: Moore's Monumental Sculpture

In the late 1940s Moore approached the pinnacle of his success, both at home and abroad. Sponsored by the British Council, Moore became Britain's most prominent cultural export. His earthbound, reassuring themes--the reclining figures, family ensembles, and abstract biomorphic forms--were suited to the ideals of the postwar world; his work resonated with the philosophy stated by the organizers of the 1948 Venice Biennale: Art must speak in a common language, inviting all people, beyond ideological barriers, into the family of man.

Moore's success allowed him to hire assistants and work on a larger scale, placing his sculpture outdoors, his lifelong dream. In 1955 he was chosen to create the most prominent sculpture for the much-heralded headquarters of UNESCO in Paris. Carved from white travertine marble, it was the first of many international commissions and his largest sculpture thus far. Size, as a defining element of his art, became increasingly important to him. "Most everything I do," Moore explained, "I intend to make on a large scale... Size itself has its own impact, and physically we can relate ourselves more strongly to a big sculpture than to a small one."

Shifting his energies away from the direct carving that had been the hallmark of his earlier style, Moore began to work increasingly in bronze. This durable material, ideally suited for outdoor sculpture, withstood his experiments with hollows and voids. Large outdoor bronze works, such as the 1971-1972 Sheep Piece in Much Hadham, bespeak Moore's ability to produce powerful work in any medium. Moore had now been firmly established as the sculptor for works in public places.

In 1968, to mark Moore's seventieth birthday, the Tate Gallery in London mounted a monumental retrospective of his work. Moore continued to work in countries around the world, with sculptures traveling to Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela, Argentina, and Japan. In 1978, he supervised the installation of Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece in front of the new East Building designed by architect I.M. Pei for the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Moore was a complex and deeply influential figure. His former student, the distinguished sculptor Anthony Caro, spoke for many younger artists when he noted in 1960 that Moore's picture "is not man-size, but screen-size." Yet, Caro also attested to the enormous impact Moore has had on an entire generation of British artists walking in his footsteps: "[He] provided an alphabet and a discipline within which to start to develop. His success has created a climate for all of us younger sculptors and has given us confidence in ourselves which without his effort we would not have felt."

A man both unassuming and driven by sparks of tremendous ego, Henry Moore made crucial contributions to the development of twentieth-century sculpture. Like many artists of his generation, Moore explored the boundaries between figuration and abstraction, inventing a formal language that celebrated the human figure at a time when representation was in crisis. After World War II, he altered our expectations about art in public places, experimenting with issues of scale and monumentality that transcended the efforts of most of his peers. His bold yet respectful handling of materials, his innovative treatment of form and space, and his deep conviction in the enduring significance of the human figure give his work unique stature in the history of modern art. In 1964, the critic Jean Clay observed that Moore's work reminds us of our umbilical cord with nature: "Moore sinks into the earth, archaic and immutable, closer to prehistory than the year 2000, even though he was born in the heart of the industrial world."

Henry Moore, Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece, 1976-1978, bronze, Gift of The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, 1978.43.1