Frederic Remington: The Color of Night

Introduction

Frederic Remington (1861–1909) has long been celebrated as one of the most gifted interpreters of the American West. Initially, his western images appeared as illustrations in popular journals. As he matured, however, Remington turned his attention away from illustration, concentrating instead on painting and sculpture. About 1900 he began a series of paintings that took as their subject the color of night. Before his premature death in 1909 at age forty-eight, Remington completed more than seventy paintings in which he explored the technical and aesthetic difficulties of painting darkness.

Surprisingly, Remington's nocturnes are filled with color and light—moonlight, firelight, and candlelight. These complex paintings testify to the artist's interest in modern technological innovations, including flash photography and the advent of electricity, which was rapidly transforming the character of night. The paintings are also elegiac, for they reflect Remington's lament that the West he had known as a young man had, by the turn of the century, largely disappeared. Although immediately recognized as extraordinary works, Remington's late nocturnes have never before been the subject of an exhibition. Frederic Remington: The Color of Night gathers together for the first time the finest of these mysterious, often deeply personal paintings.

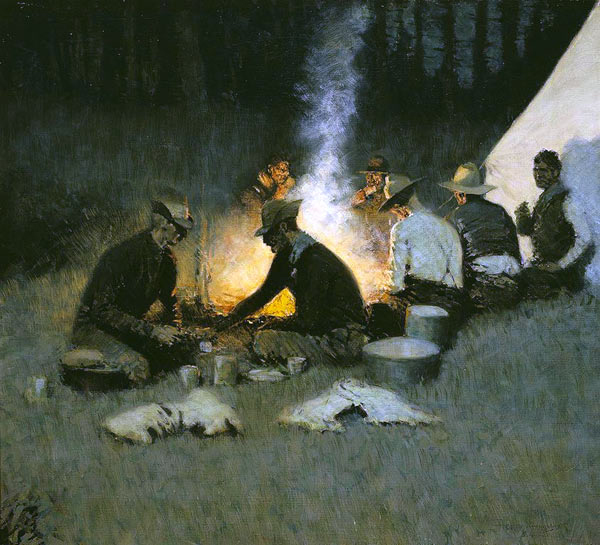

Frederic Remington, The Hunters' Supper, c. 1909, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Early Years

Frederic Sackrider Remington was born in Canton, New York, in 1861, the only son of a Civil War hero. As a young boy, he aspired to a military career, but an interest in drawing led him to Yale University, where he majored in art and joined the football team. Remington left Yale following the sudden death of his father in 1880. A subsequent series of uninspiring clerical jobs left him bored and restless.

Remington at Highland Military Academy, Worcester, Massachusetts, c. 1877, Photograph by The Notman Photographic Company, courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Early Years

In the spring of 1883, having come into his inheritance, he traveled west where he bought a sheep ranch near Peabody, Kansas. Ill suited for ranch life, he sold his property and later invested in a saloon, an endeavor that proved equally unsuccessful. His prospects were, in fact, so poor that he was initially rejected by the family of the young woman he had hoped to, and later did, marry.

(top) Frederic Remington, My Ranch (detail), 1883, courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

(bottom) Eva and Frederic Remington, Brooklyn, New York, c. 1886, Photograph courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Early Years

His luck changed, however, when Harper Brothers, the New York publisher of a popular weekly, expressed interest in several drawings of western subjects that he had brought with him when he returned east. Crudely done, these early sketches had to be redrawn by others before publication. Nevertheless, Remington soon established himself as an accurate observer of western life at a time when eastern audiences were eager for images of the Far West.

Frederic Remington, The Apache War–Indian Scouts on Geronimo's Trail, from Harper's Weekly (January 9, 1886)

Early Years

For more than a decade Remington worked at a frenetic pace, producing an astonishing number of images for popular journals. At the same time he published dozens of articles that served to enhance his reputation as a truthful reporter of life on the frontier. By the mid-1890s he was both famous and successful, but as the turn of the century approached, he deliberately set out to change the course of his career. Though not yet forty, Remington had determined that he wished to be judged a fine artist rather than simply a successful illustrator.

The Writer at Work, Ingleneuk, 1902, Photograph by Edwin Wildman, courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Early Years

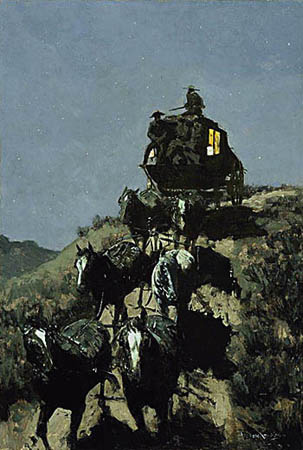

Remington's The "Hold-Up" was created as an illustration for a story published in Collier's Weekly. The tale focused on a young cavalry officer's foolish claim that robbing a stagecoach was so easy he could do it brandishing only sheepshears. Utilizing the illustrator's muted palette, Remington composed an image that gives visual form to written text.

Frederic Remington, The "Hold-Up," c. 1902, Collection of William I. Koch, Palm Beach, Florida

War Years

Fearing that his ability to paint in color had been compromised by the restrictive palette of illustration (primarily black, white, and gray), he undertook a period of intense experimentation with color. Ironically, his efforts at self-transformation were first interrupted and then aided by an unexpected event.

As the son of a war hero, Remington had long wished to observe military combat firsthand. In the spring of 1898, when the battleship Maine exploded in Havana Harbor and set off the Spanish-American War, Remington found his combat zone. Eager for an up-close look at armed conflict, he successfully secured war correspondent credentials.

(left) Frederic Remington, The Correspondent, from Colliers Weekly 32 (April 23, 1904)

(right) The Cuban War Correspondent and Colleague, Cuba, 1898 (detail), 1898, photograph courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

War Years

In June 1898, he arrived in Cuba expecting to witness a grand military spectacle. Instead, he found confusion, incompetence, and enormous suffering. In place of the glorious cavalry charges he had anticipated, Remington found American soldiers under attack from an elusive army of guerrilla fighters. Often only the “scream” of shrapnel, a new and deadly threat, signaled the approach of an enemy rarely seen. As he confronted the anxious uncertainty of jungle warfare, Remington’s ardor for combat quickly cooled.

Frederic Remington, Before the Warning Scream of the Shrapnel, from Harper's Monthly (November 1898)

War Years

The pivotal battle of the conflict began on July 1 near San Juan Hill. Though Remington was nearby on the day Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders made their famous "charge," he did not actually see the assault. Along with several other correspondents, he had taken cover behind the lines, where he witnessed, instead, the agonized suffering of the wounded. Ill with fever, Remington left Cuba shortly thereafter.

Frederic Remington, At the Bloody Ford of the San Juan, from Harper's Monthly (November 1898)

War Years

Matured, sobered, and haunted by this experience of modern warfare, Remington soon began to explore—in his art—the ramifications of what he had seen. To fulfill his obligations as a correspondent, he quickly produced a number of images documenting American troop maneuvers in Cuba.

Frederic Remington, The Charge of the Rough Riders, 1898, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Artistic Experimentation

Later, after a recuperative trip to Montana and Wyoming, he returned to the western subject matter he had so successfully made his own prior to the outbreak of war. Informed by his recent experience, however, these "western" paintings are far different in character from those that had come before.

Frederic Remington, The End of the Day, c. 1904, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Artistic Experimentation

According to a close friend, Remington became intrigued with the challenge of painting night in the fall of 1899 after seeing an exhibition of paintings in New York by a California artist named Charles Rollo Peters. An admirer of Whistler’s nocturnes, Peters had returned from a period of study abroad and begun painting moonlit views of California missions. Sixteen of these compositions were included in the exhibition that sparked Remington’s interest in the coloristic effects of moonlight.

Charles Rollo Peters, San Fernando Mission, not dated, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California, Gift of William C. Wright

The Nocturnes

Not long after seeing the Peters exhibition, Remington completed two nocturnes of his own. Both were intended to serve as illustrations for a novel he had recently written titled The Way of an Indian. Both were also transitional works, for they were dependent upon text for their full meaning. In the more striking of the two images, "Pretty Mother of the Night—White Otter is No Longer a Boy," the novel’s hero (White Otter) addresses the moon (Pretty Mother of the Night) after successfully completing a test of manhood. The spare quality of the landscape and the lack of surface detail signaled a significant change in Remington’s compositional technique.

Frederic Remington, "Pretty Mother of the Night—White Otter is No Longer a Boy," c. 1900, Bellas Artes, Nevada, LLC

The Nocturnes

Already less concerned with images that complemented or completed text, Remington soon began to compose paintings that posed, rather than answered, questions. Among the earliest of these works were two paintings from about 1902. In the first, a lone Indian—unsure whether he faces, as the title suggests, friends or foes—stares at a cluster of dwellings near the horizon.

Frederic Remington, The Scout: Friends or Foes?, 1902–1905, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

The Nocturnes

In the second work, A Reconnaissance, two figures stand at the edge of a wooded ridge, peering into a distance not visible to the viewer or to the mounted figure who waits behind. Danger, palpable yet undefined, serves as the subtext for both paintings.

Frederic Remington, A Reconnaissance, 1902, Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis, Minnesota

The Nocturnes

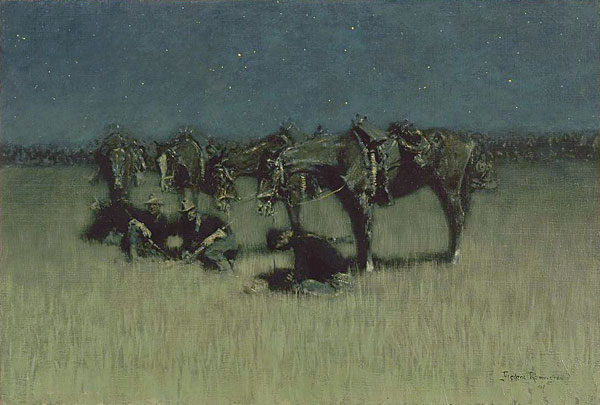

Layered, complex, and technically innovative, these images of night are also profoundly personal works of art. Filled with danger, threatened violence, and menacing silence, they mirror—metaphorically—Remington's experience of war.

Frederic Remington, Indian Scouts in the Moonlight, c. 1902, Private Collection

The Nocturnes

The Old Stage–Coach of the Plains is one of Remington's most dramatic early nocturnes. Against a starry night sky, the candlelit coach tumbles forward into the viewer’s space. A guard, his rifle poised, sits atop the coach scanning the horizon for danger, again, undefined.

Critics quickly took notice of Remington’s nocturnes and applauded his efforts, but the artist himself remained discouraged by what he perceived as his inability to capture accurately the colors of night. In 1905 he expressed his frustration to a friend: “I’ve been trying to get color in my things and still I don’t get it. Why why why can’t I get it. The only reason I can find is that I’ve worked too long in black and white. I know fine color when I see it but I just don’t get it and it’s maddening. I’m going to if I only live long enough.”

Frederic Remington, The Old Stage–Coach of the Plains, 1901, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

The Nocturnes

Remington was his own harshest critic, for in the same year that he voiced this frustration he also completed two of his finest nocturnes. In Evening on a Canadian Lake, an alarming sound or movement outside the picture plane has caught the attention of the figures in the canoe. The subject of their interest remains unknown. Remington explained his artistic approach: "Cut down and out—do your hardest work outside the picture, and let your audience take away something to think about—to imagine."

Frederic Remington, Evening on a Canadian Lake, 1905, Collection of William I. Koch, Palm Beach, Florida

The Nocturnes

In Coming to the Call, the threat is more clearly defined—a moose silhouetted against a vivid sunset sky is about to be shot by the figure in the canoe. Remington created a frozen moment of peril. Beautifully crafted and skillfully composed, these paintings confirm that Remington had left behind his illustrator’s concern with detail, pared his compositional elements to a minimum, and engaged his viewer by leaving his pictorial narratives open.

Frederic Remington, Coming to the Call, c. 1905, Collection of William I. Koch, Palm Beach, Florida

The Nocturnes

Though he continued to study the night sky and to experiment with color, Remington remained unsatisfied with the results of his efforts. It was not until June 1908 that he was able to write in his diary that he had finally discovered “how to do the silver sheen of moonlight.”

Frederic Remington, Sunset on the Plains, 1905–1906, West Point Museum Collection, United States Military Academy

The Nocturnes

Six months later, in a one-man show at Knoedler Galleries in New York, he exhibited nine stunning nocturnes. Upon seeing the exhibition one critic declared, “it would be difficult to congratulate Mr. Remington too warmly” for his “night scenes.” Another reviewer wrote, “He has grown to think through his paint so freely and fluently that in some of his more recent work he seems to have used his medium unconsciously, as a great musician does his piano and score.”

Frederic Remington, The Grass Fire (Backfiring), 1908, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

The Nocturnes

Among the paintings that inspired such praise was an eerie moonlit scene titled Apache Scouts Listening. Between diagonal bands of cast shadows and receding trees, several Indian scouts crouch, listening to a sound outside the picture plane. At the center, a trooper, his hand to his ear, strains to hear the same unidentified sound. An entry in Remington’s ledger suggests that he composed the painting while recalling a particular threat: those who attempted to pass undetected through Indian territory feared camp dogs above all else, for their barking gave away the intruder’s position and resulted in certain death. Nowhere in his painting, however, does Remington offer a clue regarding the nature of the sound that has caused the alarm. Again, his beautifully crafted painting poses questions but offers no answers.

Frederic Remington, Apache Scouts Listening, 1908, Private Collection

The Nocturnes

Similar questions are raised (but not answered) in another work exhibited in the 1908 exhibition at Knoedler’s. In The Call for Help wolves stalk three terrified horses cowering against the rails of a fence. Light in a distant window suggests the nearby cabin is occupied. Will someone intervene? Will the violence about to erupt in the corral be averted? Remington’s composition offers no resolution, only a frozen moment of panic.

Frederic Remington, The Call for Help, c. 1908, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, The Hogg Brothers Collection, Gift of Miss Ima Hogg

The Nocturnes

In December 1909, shortly before his premature death from complications following an appendectomy, Remington affixed a newspaper clipping to a page of his diary. Reviewing the last of his exhibitions at Knoedler’s, an unidentified critic had written “in all of Remington’s pictures the shadow of death seems not far away. If the actors in his vivid scenes are not threatened by death in terrible combat, they are menaced by it in the form of famine, thirst or cold.” Among the works that prompted such commentary was one of Remington’s last nocturnes, The Luckless Hunter. At the center of the composition a lone figure, huddled against the cold, rides a small Indian pony across an empty, snow-blown plain. Hunger and starvation are the true subjects of this painting; death the menace that lurks close by.

Frederic Remington, The Luckless Hunter, 1909, Sid Richardson Collection of Western Art, Fort Worth, Texas

The Nocturnes

In another late work, Remington created an image that destroyed the comforting distance viewers might have felt when considering the grim implications of such paintings as The Luckless Hunter. In Moonlight, Wolf Remington succeeded in turning the viewer into potential prey. Isolated at the center of the canvas, a lone wolf stares with narrowed eyes into the viewer’s space. Frozen in its tracks, the wolf appears to have heard an alarming sound. There is, however, no agent within the painting for the wolf to act upon. Instead, the fixated eyes of Remington’s wolf engage the viewer and cast that individual as either the source of the animal’s alarm or the object of its attack. The threat of danger, an element present in nearly all of Remington’s nocturnes, is now directed out, toward the viewer.

Frederic Remington, Moonlight, Wolf, c. 1909, Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts, Gift of the Members of the Phillips Academy Board of Trustees on the occasion of the 25th Anniversary of the Addison Gallery

The Nocturnes

During the last decade of his life, the first of the twentieth century, Remington completed more than seventy nocturnes. Astonishing in their coloristic effects, these paintings reflect an artistic consciousness tempered by war and loss.

Frederic Remington, Night Halt of Cavalry, 1908, Private Collection

The Nocturnes

Stripped of extraneous detail, the paintings are modern in their spare compositional structure and in their anxious uncertainty.

Frederic Remington, The Sentinel, 1907, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

The Nocturnes

As one critic noted, the figures in Remington’s nocturnes are stalked by death. Death’s “shadow” had been the subject of nocturnal images in the past, but Remington’s late nocturnes are focused less on the certainty of death, than on the anxiety, the fear that death may appear at any time.

Frederic Remington, The Hungry Moon, 1906, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

The Nocturnes

Crafted with exceptional care, these dark and seemingly dangerous nocturnes are at once an elegaic evocation of the Old West, and an expression of a deep and pervasive sense of disquiet. Their stark compositions and reductive tone add a surprisingly modern component to Remington's art.

Frederic Remington, In From the Night Herd, 1907, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Gift of Albert K. Mitchell

The Nocturnes

With stunning tonal and atmospheric effects, each offers a frozen moment haunted by danger and violence.

Frederic Remington, The Stampede by Lightning, 1908, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

The Nocturnes

The nocturnes drew immediate approval from critics, as evidenced by this contemporary review of Remington's 1909 Knoedler Gallery exhibition:

"...as a manipulator of the medium, he is fast becoming free, easy, facile. His improvement during the past few years is remarkable.... Beautifully drawn backs of horses, brilliant faces of men on the offside of a camp fire, green reflections of snow and a dark forest...are admirably rendered....[These paintings stand as] a record of the kind of life led by our men on duty in the West and as proof of Mr. Remington's gift as a painter."

These compelling and provocative paintings of night—some of which have not been exhibited in nearly a century—also helped establish Remington's reputation as one of the most gifted colorists of his generation.

Photograph of the artist, courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Credits

This Web feature was based on the catalogue essay and other exhibition materials written by Nancy K. Anderson; it was designed and produced by Donna Mann, and edited by Julie Warnement. Phyllis Hecht, Abbie Sprague, Mariah Shay, Amanda Mister Sparrow, Lesley Keiner, Rachel Kunkle, and Naomi Remes also contributed to this project. We thank the many institutional and private lenders to the exhibition, as well as the owners of the works used as comparative illustrations, who graciously have permitted their inclusion in our online feature.

Photo Credits

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts

Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Bellas Artes, Nevada, LLC

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California

Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

William I. Koch, Palm Beach, Florida

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Private Collection

Sid Richardson Collection of Western Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

West Point Museum Collection, United States Military Academy

Frederic Remington, Shotgun Hospitality, 1908, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, Gift of Judge Horace Russell, Class of 1865