Toulon, Gare (Toulon, Train Station)

1861 or later

Édouard-Denis Baldus

Artist, French, 1813 - 1889

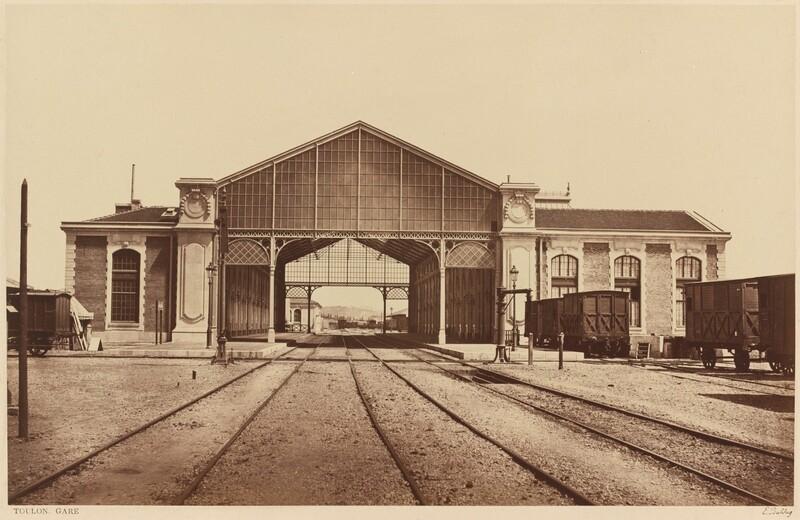

Édouard-Denis Baldus photographed the train station in Toulon while on commission for the administrative council of the southern region of the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM) railroad. With his characteristic eye for majesty, Baldus presents a grand yet simple view. Positioning himself central to his subject, with the slender train tracks receding from middle foreground into the frame's depths, Baldus entices viewers into a scene that sparkles with detailed clarity. From the crisscross geometry of iron and glass of the main station, to the crisp shadow cast by a tiny lamppost beyond, virtually every element shimmers in a sun-drenched setting devoid of people and extraneous detail. The image, secured in the glossy sepia tones of albumen, celebrates modern materials as it pays homage to "the Iron Horse" that was rapidly transforming the lives it connected along its newly opened southern rail line.

Toulon, Gare is the last work in a sequence of 69 photographs in the album Chemins de fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée, considered by some the finest photographic album from 19th-century France.1 Taken in its entirety, the album aligns the engineering feats of Second Empire France with the nation's past architectural grandeur. Using negatives made specifically for the project, as well as a selection culled from earlier commissions, Baldus juxtaposed images of Roman ruins and medieval monuments with those of newly built viaducts, railways, and tunnels. The composition of the album makes no mystery of Baldus' appreciation for the beauty of the industrial landscape, nor of his conviction that these neoteric structures were part of a historical continuum.

Like other peintres-photographes (painters-turned-photographers) of his generation, including Gustave Le Gray, Henri Le Secq, and Charles Nègre, Baldus used the camera in a somewhat retrograde manner, with one foot in the past and the other poised for the future. This vacillating stance, ranging in tenor from repulsion to adoration for all things modern, prevailed in a society that saw old buildings reduced to rubble as elaborate new architectural enterprises rose in their stead. Several government-sponsored projects employed the enthusiastic services of the peintres-photographes to document their campaigns. Baldus participated in many of these historic endeavors, including the Missions Héliographiques of 1851 (which also included Le Gray, Le Secq, Hippolyte Bayard, and O. Mestral) and the construction of the new Louvre in 1855–1857. He also produced several elaborate albums, presenting one each to Queen Victoria and Napoléon III. By the time he received the PLM commission, Baldus had a well-earned reputation as one of the finest architectural and industrial landscape photographers of his day.

That Baldus employed the wet plate collodion process, which relies on a glass negative, for Toulon, Gare is significant. Though Baldus was a master at orchestrating impressively detailed prints from paper negatives, the images he printed from glass negatives onto glossy albumen paper allowed for even finer definition. Such photographs fed a public hungry for "transparent" images whose precision suggested (erroneously) the primacy of seamless technical vision over artistic intervention.2

As the ease and clarity of the collodion process conjoined with innovations in print production, paper negative photography quickly faded. Baldus, a brilliant technician in both techniques, effectively made the transition.3 An enthusiastic innovator, he investigated elaborate methods of combination printing and multi-negative panoramic views. His commanding sense of composition and tone, evident in Toulon, Gare, appealed to the imperial eyes of a nation whose focus on industry and expansion as the secular religion of the future was sharp and undeterred.

(Text by April Watson, published in the National Gallery of Art exhibition catalogue, Art for the Nation, 2000)

Notes

1. André Jammes and Eugenia Parry Janis, The Art of French Calotype (Princeton, 1983), 140.

2. Baldus, who never fully departed from his training as a painter, did not shy from creative intercession. His photographs were frequently printed from combined negatives and retouched. For more on this subject, see Malcolm Daniel, The Photographs of Édouard Baldus (New York, 1994), 21–22.

3. Other peintres-photographes who preferred the diffuse renderings of paper negative photography were pushed to the fringes. Henri Le Secq, who worked exclusively with paper negatives his entire career, effectively gave up the art after 1856. Gustave Le Gray, who was considered aesthetically retrograde for championing paper negatives while others heralded collodion on glass, left his family destitute in Marseilles and took flight to Egypt sometime between 1860 and 1865.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

albumen print

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

sheet (trimmed to image): 27.4 x 43.1 cm (10 13/16 x 16 15/16 in.)

support: 45.4 x 60.6 cm (17 7/8 x 23 7/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1995.36.10

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

David and Mary Robinson, Sausalito, CA; NGA purchase, 1995.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1986

19th Century Photographs from the Collection of Mary and David Robinson, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, 1986.

1989

On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Art Institute of Chicago; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989-1990.

1995

The First Century of Photography: New Acquisitions, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1995.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000-2001.

2015

In Light of the Past: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Collecting Photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 3 – July 26, 2015

2019

The Eye of the Sun: Nineteenth-Century Photographs from the National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2019, unnumbered catalogue.

Bibliography

1989

Greenough, Sarah, Joel Snyder, David Travis, and Colin Westerbeck. On the Art of Fixing a Shadow: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Photography. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Art Institute of Chicago, 1989: pl. 65.

1994

Daniel, Malcolm. The Photographs of Edouard Baldus. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994, illus. pl.86.

Inscriptions

all on mount: lower left stamped in black ink: TOULON. GARE; lower right stamped in black ink: E. Baldus

Wikidata ID

Q64147067