Still Life with Ham

1650

Gerret Willemsz Heda

Painter, Dutch, active 1640s and 1650s

The array of objects in this tabletop still life by Gerret Willemsz Heda, including an elaborate salt cellar, a pewter pitcher, a tall fluted glass, and the prominent ham, evokes the prosperity the Dutch enjoyed around the middle of the seventeenth century. The white linen tablecloth is crumpled so that various objects nestle in its folds, which allows the artist to show off his skill in depicting drapery and the sheen of linen through varied effects of light and shade. The partially consumed food and drinks and the disarray of the cloth give the impression that people have just stepped away from the table.

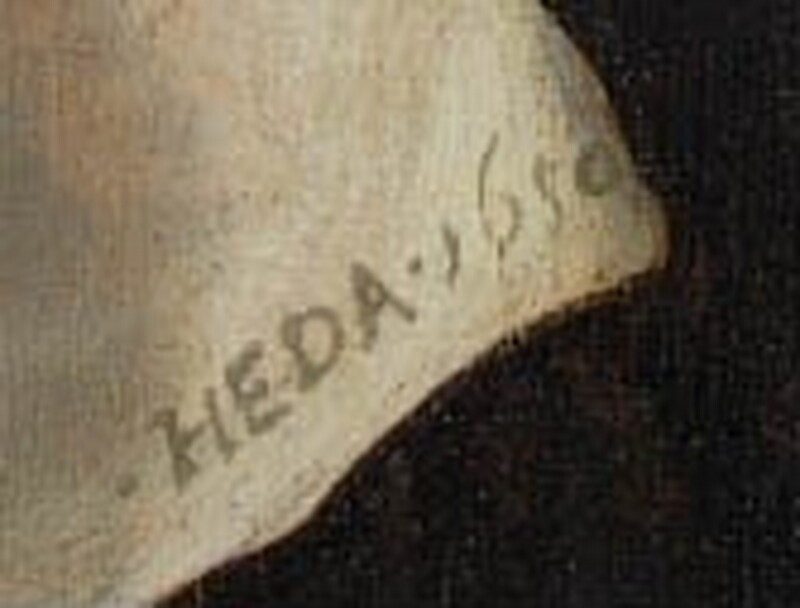

Gerret was the son and pupil of the great still-life master Willem Claesz Heda (1594-1680). In his choice of subject matter, style, and ability, Gerret compares sufficiently close to his father that it is not always easy to distinguish between the two. Still Life with Ham, signed and dated "HEDA 1650," initially entered the National Gallery’s collection as a work by Willem, but subtle differences in style and concept point to the talented hand of Gerret. Still Life with Ham ranks among Gerret’s finest works.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 98.5 x 82.5 cm (38 3/4 x 32 1/2 in.)

framed: 123.2 x 108 x 8.9 cm (48 1/2 x 42 1/2 x 3 1/2 in.) -

Accession Number

1985.16.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

John S. Thacher [1904-1982], Washington, D.C.; bequest 1985 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1997

Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch Paintings from the National Gallery of Art, The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, 1997, unnumbered brochure, repro.

2002

Matters of Taste: Food and Drink in 17th Century Dutch Art and Life, Albany Institute of History and Art, 2002, no. 23, repro.

2004

Pieter Claesz: Master of Haarlem Still Life, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem; Kunsthaus Zürich; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2004-2005, not in catalogue (shown only in Washington).

Bibliography

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Grand Rapids and Kampen, 1986: 309.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 96-98, color repro. 97.

1997

Hess, Catherine and Timothy Husband. European Glass in The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 1997: no. 50j, repro.

Chrysler Museum of Art. Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch paintings from the National Gallery of Art. Exh. brochure. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk. Washington, 1997: unnumbered repro.

2000

Meijer, Fred G. "Boekbespreking van...[three books related to still-life paintings, primarily from the Netherlands]." Oud Holland 114, no. 2/4 (2000): 233, fig. 7, 236 n. 37, as by Gerret Willemsz Heda and Willem Claesz Heda.

Meijer, Fred G. "Review of three books on still-life paintings " _Oud Holland _ 114, no. 2/4 (2000): 233, fig. 7, repro; and 236, note 37, as by both Gerret Willemsz Heda and Willem Claesz Heda.

2002

Barnes, Donna R., and Peter G. Rose. Matters of Taste: Food and drink in seventeenth-century Dutch art and life. Exh. cat. Albany Institute of History & Art. Syracuse, 2002: 74-75, no. 23, repro.

2003

Gregory, Quint (Henry D. Gregory V). "Tabletop still lifes in Haarlem, c. 1610-1660: a study of the relationships between form and meaning." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, 2003: 3-18, 172, 201.

Inscriptions

on the right edge of the tablecloth: .HEDA. 1650

Wikidata ID

Q20177352