Flowers in an Urn

c. 1720/1722

Jan van Huysum

Artist, Dutch, 1682 - 1749

Against a pale greenish-ocher background, the subtle colors and organic rhythms of Jan van Huysum’s exuberant flower arrangement in an urn create an elegant whole, without focusing unduly upon any individual blossom. The bouquet is in a terra-cotta vase decorated with playful cupids, and near it are three pale blue eggs in a bird’s nest, which teeters on the edge of the marble tabletop. Like Jan Davidsz de Heem, the famous still-life artist on whose work he must have drawn for inspiration, Van Huysum introduced improbable combinations of flowers in his paintings as well as a wide variety of insects to enliven his image. The lighter tonal background of this work, which enhances its delicate and decorative quality, is characteristic of the artist’s later style.

Van Huysum’s lasting fame rests on his technical virtuosity and his precise observations of flowers and fruit. It has never been determined how he achieved such high degrees of accuracy because he was an extremely secretive artist. Nevertheless, it seems that he painted most of his flowers directly from life or from models he had previously drawn from life. In a letter to a patron he complained that he could not finish a still life that was to include a yellow rose until that flower blossomed the following spring.

West Building Ground Floor, Gallery G13

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 79.9 x 60 cm (31 7/16 x 23 5/8 in.)

framed: 99.7 x 80.6 x 8.2 cm (39 1/4 x 31 3/4 x 3 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1977.7.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Jacques Goudstikker, Amsterdam), by 1919 until at least 1920. Vas Diag, before 1924; (Leggatt Brothers, London); acquired 21 July 1924 by Lord Claud Hamilton;[1] by inheritance to his widow, Lady Claud Hamilton; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 28 November 1975, no. 23); (Alexander Gallery, London); purchased 18 February 1977 by NGA.

[1] The provenance from Vas Diag to Lord Hamilton is given in a letter from Charles Leggatt to Arthur Wheelock, 31 December 1982, in NGA curatorial files. Records of the Leggatt Brothers that might have provided more information about Diag and the purchase from him were destroyed in World War II. “Lord Claud Hamilton” could be one of several people; one possibility is that he was Lord Claud Nigel Hamilton (1889–1975), whose widow (she died 1984) was born Violet Ruby Ashton, and was earlier Mrs. Keith W. Newall.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1919

Collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam, Pulchri Studio, The Hague, 1919, no. 13.

1920

Collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam, Kunstkring, Rotterdam, 1920, no. 24.

1976

Spring Exhibition, Alexander Gallery, London, 1976.

1997

Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch Paintings from the National Gallery of Art, The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, 1997, unnumbered brochure, repro.

1998

The Age of Opulence: Arts of the Baroque, Oklahoma City Art Museum, 1998-1999, brochure, repro.

Bibliography

1919

Goudstikker, Jacques. Catalogue de la collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam. Exh. cat. Pulchri Studio, The Hague. Haarlem, 1919: no. 13.

1920

Goudstikker, Jacques. Catalogue de la collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam. Exh. cat. Rotterdamsche Kunstkring. Rotterdam, 1920: no. 24.

1954

Grant, Maurice Harold. Jan van Huysum, 1682–1749. Leigh-on-Sea, 1954: no. 3.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 208, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 144-145, color repro. 143.

1997

Chrysler Museum of Art. Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch paintings from the National Gallery of Art. Exh. brochure. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk. Washington, 1997: unnumbered repro.

1998

Oklahoma City Art Museum. The Age of Opulence: Arts of the Baroque. Exh. brochure. Oklahoma City Art Museum, Oklahoma City, 1998: unnumbered repro.

2006

Segal, Sam, Mariël Ellens, and Joris Dik. De verleiding van Flora: Jan van Huysum, 1682-1749. Exh. cat. Museum het Prinsenhof, Delft; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Zwolle, 2006: 173, repro.

2007

Segal, Sam. The Temptations of Flora: Jan van Huysum, 1682-1749. Translated by Beverly Jackson. Exh. cat. Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Zwolle, 2007: 173, repro.

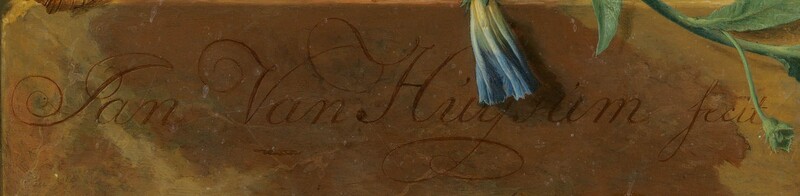

Inscriptions

lower left on front of marble tabletop: Jan Van Huysum fecit

Wikidata ID

Q20177790