Moses Striking the Rock

1624

Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael

Artist, Dutch, c. 1566 - 1638

This depiction of Moses Striking the Rock exemplifies Joachim Wtewael's lifelong commitment to mannerism. The mannerists' use of alternating patterns of light and dark, elongated figures, contorted poses, and pastel colors created elegant yet extremely artificial scenes. This multilayered scene from the Book of Exodus describes the miraculous moment in the arid wilderness when God enabled Moses, who was leading the Israelites out of Egypt, to make water gush from the rock at Horeb. Moses, striking the rock with the same rod he had used to part the Red Sea, stands next to his brother, the high priest Aaron, while around them voluptuous women, children, and a host of animals partake of the refreshing water.

The story of Moses and his struggles to lead the Israelites out of bondage had special meaning to the Dutch, who drew parallels between that biblical story and their own quest for independence from Spanish rule. The initial leader and hero of the Dutch Revolt, Prince William "the Silent" of Orange, became symbolically identified with Moses. Like his biblical counterpart, the Prince, who was assassinated in 1584, did not live to see the realization of his "promised land," a Dutch Republic independent from Spanish rule. Wtewael was a fervent supporter of the House of Orange in its quest to lead all seventeen Netherlandish provinces to independence. His decision to paint this scene in 1624 may reflect an effort on his part to revitalize the allegorical connections between Moses and the House of Orange after the conclusion of the Twelve Year Truce in 1621, at a time when William's son and successor, Prince Maurits, and the latter's half-brother, Prince Frederik Hendrik, were renewing their military efforts against Spanish aggression.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 44

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 44.6 x 66.7 cm (17 9/16 x 26 1/4 in.)

framed: 58.7 x 80.7 cm (23 1/8 x 31 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1972.11.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Sale, Foster, London, 29 November 1833, no. 29, as by J. de Wael); Thomas Chawner, Esq. [d. 1851], London and Addlestone, near Chertsey, Surrey; (his estate sale, Foster, London, 16 June 1852, no. 97); Chance.[1] H. Charles Erhardt, Esq., London, by 1892; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 19-22 June 1931, no. 273, as by J.B. de Wael); "Leffer" or "Lepper."[2] Francis Howard, Esq., Dorking, by 1955; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 25 November 1955, no. 52, as by J.B. de Wael); (Arcade Gallery, London); sold to Vincent Korda, London; repurchased 1967 by (Arcade Gallery, London);[3] sold 1967 to (Edward Speelman, London);[4] purchased 31 January 1972 by NGA.

[1] Burton Fredericksen (letter of 2 January 2003 and e-mail of 17 July 2003, in NGA curatorial files) has kindly provided the information about the Foster sales of 1833 and 1852, and the buyers at each sale, Thomas Chawner and "Chance." A label on the back of the painting, which reads "J. de Wael / 29 Moses striking the Rock," matches the information from the 1833 sale catalogue.

[2] Christie's in London no longer has its records from 1931 and thus was not able to help clarify the buyer's name. See correspondence from 25 September 1986 and 7 November 1986, in NGA curatorial files.

[3] The Arcade Gallery, in a letter of 3 March 1987 in NGA curatorial files, says that they sold the painting "almost immediately" to Korda after they purchased it at the 1955 sale, repurchased it in 1967, and then sold it during the exhibition in November and December of the same year, in which the painting appeared.

[4] A letter from Anthony Speelman of 23 January 1987, in NGA curatorial files, indicates that the Edward Speelman firm had bought Moses Striking the Rock from Vincent Korda prior to their selling it to the National Gallery of Art.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1892

A Loan Exhibition of Pictures, Art Gallery of the Corporation of London, Guildhall, 1892, no. 99, as by Jan Baptist de Wael.

1967

Recent Acquisitions: Mannerist and Baroque Paintings, Arcade Gallery, London, 1967, no. 23.

1980

Gods, Saints and Heroes: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Detroit Institute of Arts; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1980, fig. 1 (shown only in Washington).

1998

A Collector's Cabinet, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1998, no. 66.

2000

Landscape of the Bible: Sacred Scenes in European Master Paintings, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 2000-2001, no. 13, repro.

2015

Pleasure and Piety: The Art of Joachim Wtewael (1566-1638), Centraal Museum, Utrecht; National Gallery of Art, Washington; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2015-2016, no. 39, repro.

Bibliography

1892

Temple, Alfred G. Descriptive catalogue of the loan collection of pictures. Exh. cat. Art Gallery of the Corporation of London, 1892: no. 99, as by Jan Baptist de Wael.

1967

The Arcade Gallery. Recent Acquisitions: Mannerist and Baroque Paintings. Exh. cat. Arcade Gallery, London, 1967: no. 23.

1974

Lowenthal, Anne Walter. "Wtewael’s Moses and Dutch Mannerism." Studies in the History of Art 6 (1974): 124-141, fig. 1.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 358, repro.

Lowenthal, Anne Walter. "The paintings of Joachim Anthonisz. Wtewael: (1566-1638)." Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, 1975: 322-324, A-66.

1980

Blankert, Albert, et al. Gods, Saints, and Heroes: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Detroit Institute of Arts; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Washington, 1980: 46-47, fig. 1.

1982

Sutton, Peter C. "The Life and Art of Jan Steen." Special edition of Bulletin of the Philadelphia Museum of Art 78, no. 337-338 (Winter-Spring 1982/1983): 18.

1983

Tümpel, Christian. "Die Reformation und die Kunst der Niederlande." In Luther und die Folgen für die Kunst. Edited by Werner Hofmann. Exh. cat. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Munich, 1983: 314-315, fig. 15.

1984

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1984: 5, 8, 9, repro.

1985

Waterhouse, Ellis K. Around 1610: The Onset of the Baroque. Exh. cat. Matthiesen Fine Art, London, 1985: 90.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 440, repro.

Bosque, Andrée de. Mythologie et Maniérisme aux Pays-Bas, 1570–1630: Peinture, dessins. Antwerp, 1985: 94, 95, repro.

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 454.

Lowenthal, Anne Walter. Joachim Wtewael and Dutch Mannerism. Doornspijk, 1986: 41, 50-51, 55, cat. A-88, 151-152, color pl. 22.

Wansink, Christina J. A. "A ‘Mercury, Argus and Io’ from Utrecht." Hoogsteder-Naumann Mercury 4 (1986): 3, 4, fig. 2.

1992

National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1992: 122, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 394-398, color repro. 395.

1998

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. A Collector's Cabinet. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998: 68, no. 66.

2000

Pessach, Gill. Landscape of the Bible: sacred scenes in European master paintings. Exh. cat. Muzeon Yisrael, Jerusalem, 2000: 19, 72-73, no. 13, repro.

2012

Tummers, Anna. The Eye of the Connoisseur: Authenticating Paintings by Rembrandt and His Contemporaries. Amsterdam, 2012: 204, 205, color fig. 128.

2014

Wheelock, Arthur K, Jr. "The Evolution of the Dutch Painting Collection." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 50 (Spring 2014): 2-19, repro.

2020

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Clouds, ice, and Bounty: The Lee and Juliet Folger Collection of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2020: 26, fig. 12, 27.

Inscriptions

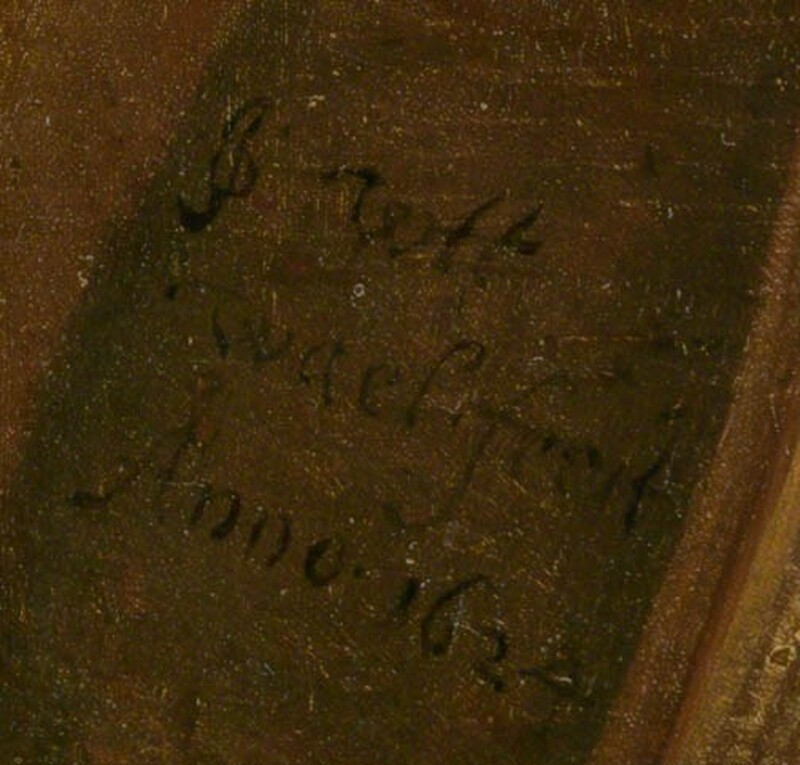

lower left, JO in ligature: JO Wtt / wael fecit / Anno.1624

Wikidata ID

Q20177037