The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

1398-1399

Paolo di Giovanni Fei

Painter, Sienese, c. 1335/1345 - 1411

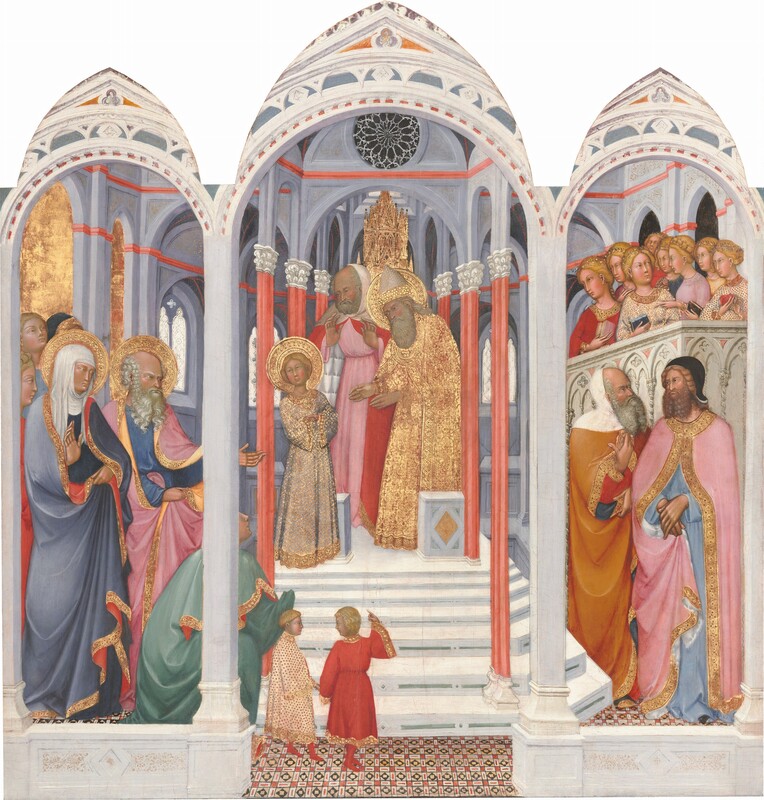

This engaging narrative scene was the center panel of an altarpiece commissioned in 1398 for the Chapel of Saint Peter, near the high altar of the cathedral in Siena. It would have been flanked, in all probability, by standing saints—one of them Peter—and surmounted by other saints shown half-length. Originally, the structure would have been gabled at the top, with elaborate gold moldings framing each section.

According to legend, the Virgin entered the temple in Jerusalem at age three and remained until she was 14. In this depiction, she stands at the top of the long stair with a last sidelong look at her parents, yet she remains fearless and strong. Like those of the high priest who receives her, Mary’s robes are splendid gold brocade. These were created with a technique called sgraffito, in which paint is scraped away in patterns to reveal gilding below that is then textured with tiny punches. Equally lavish is the interior of Solomon’s temple, which is treated as a Gothic church. The complex space is easily read, airy with lots of light and a brilliant palette—cool blues, salmony pinks, and glassy greens. A gallery at the right is filled with the girls who will be Mary’s companions. One, at the back, seems to be on tiptoe, trying hard to see this girl who would be fed each day by an angel. On the other side, near Mary’s parents, Anna and Joachim, another onlooker cranes for a glimpse and a woman kneels, her face half hidden by a pillar. Such rich details enliven and humanize a sacred event, making it more accessible to a contemporary viewer.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 3

Artwork overview

-

Medium

tempera on wood transferred to hardboard

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

painted surface: 146.1 × 140.3 cm (57 1/2 × 55 1/4 in.)

overall: 147.2 × 140.3 cm (57 15/16 × 55 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1961.9.4

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Commissioned in 1398[1] for the chapel of San Pietro in Siena Cathedral,[2] where it remained at least until 1482.[3] It is probable, however, that the altarpiece was removed only between 1580 (when a new, richly decorated marble altar was commissioned for the chapel) and 1582 (when the decoration of the new altar was completed). At this time it was then either consigned to the cathedral’s storerooms or sold.[4] H.M. Clark, London, by 1928.[5] Edward Hutton [1874-1969], London.[6] (Wildenstein & Co., New York), by 1950;[7] sold February 1954 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York;[8] gift 1961 to NGA.

[1] Gaetano Milanesi, Documenti per la storia dell'arte senese, 3 vols., Siena, 1854: 2:37; Scipione Borghesi and Luciano Banchi, Nuovi documenti per la storia dell'arte senese 1, Siena, 1898: 62; Monica Butzek, "Chronologie," In Die Kirchen von Siena, multi-vol., ed. Waltee Haas and Dethard von Winterfeld, vol. 3, part 1.1.2, Munich, 2006: 102. Payments to Paolo di Giovanni Fei “per la tavola di sancto Piero et sancto Pavolo, per sua fatiga e colori” were made, specifies Monica Butzek (2006), between 1398 and April 1399.

[2] Pietro Lorenzetti’s altarpiece of the Birth of the Virgin, also painted for the Cathedral of Siena in 1342 (see Carlo Volpe, Pietro Lorenzetti, ed. Marco Lucco, Milan, 1989: 152-154), is surmounted, like The Presentation of the Virgin discussed here, by three arches included in a heavy frame. The present appearance of these paintings is misleading, however. Fourteenth-century altarpieces were generally realized on rectangular panels, not silhouetted like these, and integrated above by triangular or trapezoidal gables partially overlapped by the integral frame. See Monika Cämmerer George, Die Rahmung der toskanischen Altarbilder in Trecento, Strasbourg,1966: 144-165; Christoph Merzenich, Vom Schreinerwerk zum Gemälde. Florentiner Altarwerke der ersten Hälfe des Quattrocento, Berlin, 2001: 43-56.

[3] Enzo Carli, Il Duomo di Siena, Genoa, 1979: 85-86.

[4] On 9 September 1579, the Congrega di San Pietro, patron since 1513 of the chapel dedicated to this saint (the second altar from the entrance in the north aisle), commissioned the stonecutters Girolamo del Turco and Pietro di Benedetto da Prato to realize a new marble structure around the altar. This sculptural decoration was completed in April 1582. It is presumed that between the two dates Paolo’s panel, considered antiquated, was removed. See Butzek 2006, 197.

[5] Daily Telegraph Exhibition 1928, 162. Concerning the unknown whereabouts of the painting between 1582 and 1928, a handwritten note on a photograph of the painting, formerly owned by Bernard Berenson (now in the Biblioteca Berenson at Villa I Tatti, Florence), suggests a provenance from the collection at Corsham Court, Wiltshire, which the British diplomat Sir Paul Methuen (1672–1757) had formed in the eighteenth century, and which, by the mid-nineteenth century, had been enriched with paintings from the collection of the Rev. John Sanford (1777-1855) through the 1844 marriage of Sanford’s daughter and sole heir, Anna Horatia Caroline Sanford (1824–1899), to Frederick H.P. Methuen, 2nd baron Methuen (1818-1891). See Benedict Nicolson, "The Sanford Collection," The Burlington Magazine 98 (1955): 207–214. However, this suggestion appears to be in error. James Methuen-Campbell, who inherited Corsham Court in 1994 and has extensively researched the family collections, kindly reviewed the manuscript material for both the Sanford and Methuen collections, and found no reference to the painting (see his e-mail to Anne Halpern, of 15 February 2012, in NGA curatorial files). The painting also does not appear among those disposed of by Sanford on the occasion of two London sales: a sale by private contract under the auspices of George Yates (24 April 1838, and days following), and a sale at Christie & Manson (9 March 1839).

[6] Information given in Paintings and Sculpture from the Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1956.

[7] According to the handwritten note on the photograph referenced above (see note 5), the painting was with Wildenstein by October 1950.

[8] The bill of sale (copy in NGA curatorial files) is dated 10 February 1954, and was for fourteen paintings, including Presentation of the Virgin by Bartolo di Fredi; payments by the foundation continued to March 1957. See also The Kress Collection Digital Archive, https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/objects/2275.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1928

Daily Telegraph Exhibition of Antiques and Works of Art, Olympia, London, 1928, no. X1, as by Bartolo di Fredi.

Bibliography

1928

The Daily Telegraph at Olympia, ed. The Daily Telegraph Exhibition of Antiques and Works of Art. Exh. cat., Olympia, London, 1928: 162.

1951

Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death. Princeton, 1951: 28, fig. 165.

1956

Paintings and Sculpture from the Kress Collection Acquired by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation 1951-56. Introduction by John Walker, text by William E. Suida and Fern Rusk Shapley. National Gallery of Art. Washington, 1956: 28, repro., as by Bartolo di Fredi.

1959

Paintings and Sculpture from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1959: 35, repro., as by Bartolo di Fredi.

1960

Campolongo, Elizabetta. "Fei, Paolo di Giovanni." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Edited by Alberto Maria Ghisalberti. 82+ vols. Rome, 1960+: 46(1996):15, 16.

1964

Mallory, Michael. "Towards a Chronology for Paolo di Giovanni Fei." The Art Bulletin 46 (1964): 529-535, figs. 1, 3, 4.

Lafontaine-Dosogne, Jacqueline. Iconographie de l’enfance de la Vierge dans l’Empire byzantin et en Occident. 2 vols. Bruxelles, 1964-1965: 2:30 n. 1.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 49.

Mallory, Michael. "Paolo di Giovanni Fei." Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, 1965. Ann Arbor, MI, 1973: 3, 116-141, 237, fig. 50.

1966

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII-XV Century. London, 1966: 62, fig. 159.

Schiller, Gertrud. Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst. 6 vols. Gütersloh, 1966-1990: 4, pt. 2:71.

Mallory, Michael. "An Early Quattrocento Trinity." The Art Bulletin 48 (1966): 86, fig. 2.

1967

Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, 1967: 250.

Denny, Don. "Simone Martini’s The Holy Family." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute 30 (1967): 139 n. 4.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 42, repro.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London, 1968: 1:130. 2:pl. 418.

1969

Mallory, Michael. "A Lost Madonna del Latte by Ambrogio Lorenzetti." The Art Bulletin 51 (1969): 42 n. 14.

Os, Hendrik W. van. Marias Demut und Verherrlichung in der sienesischen Malerei: 1300-1450. The Hague, 1969: 6, fig. 4.

1971

Carli, Enzo. I pittori senesi. Siena, 1971: 22, 133, fig. 115.

1972

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 69, 300, 647.

"Paolo di Giovanni Fei." In Dizionario Enciclopedico Bolaffi dei pittori e degli Incisori italiani: dall’XI al XX secolo. Edited by Alberto Bolaffi and Umberto Allemandi. 11 vols. Turin, 1972-1976: 8(1975):315.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 126, repro.

1977

Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. I Dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa, 1977: 179, 180, 202.

Maginnis, Hayden B. J. "The Literature of Sienese Trecento Painting 1945-1975." Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 40 (1977): 300.

Bennett, Bonnie Apgar. Lippo Memmi, Simone Martini’s “fratello in arte”: The Image Revealed by His Documented Works. PhD diss. University of Pittsburgh, 1977. Ann Arbor, MI, 1979: 136, 143, 250 n. 24, fig. 76.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. Washington, 1979: 1:175-177; 2:pl. 122.

Carli, Enzo. Il Duomo di Siena. Genoa, 1979: 85-86.

1981

Carli, Enzo. La pittura senese del Trecento. 1st ed. Milan, 1981: 241, fig. 282.

1982

Il gotico a Siena: miniature, pitture, oreficerie, oggetti d’arte. Exh. cat. Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. Florence, 1982: 295, 296, 298, 317.

1983

L’Art gothique siennois: enluminure, peinture, orfèvrerie, sculpture. Exh. cat. Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon. Florence, 1983: 277, 278, 284.

Carli, Enzo. Sienese Painting. New York, 1983: 48.

Early Italian Paintings and Works of Art 1300-1480 in Aid of the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum. Exh. cat. Matthiesen Fine Art, London, 1983: 34.

Frederick, Kavin. "A Program of Altarpieces for the Siena Cathedral." The Rutgers Art Review 4 (1983): 26-29, fig. 4.

1984

Torriti, Piero. "Un’aggiunta a Paolo di Giovanni Fei." in Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di Roberto Salvini. Florence, 1984: 211-212.

Os, Hendrik W. van. Sienese Altarpieces 1215-1460. Form, Content, Function. 2 vols. Groningen, 1984-1990: 2(1990):135-137, repro.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 299, repro.

Riedl, Peter Anselm, and Max Seidel, eds. Die Kirchen von Siena. 3 vols. Munich, 1985-2006: 1(1985), pt. 1:123, 124.

Os, Hendrik W. van. "Tradition and Innovation in Some Altarpieces by Bartolo di Fredi." The Art Bulletin 67 (1985): 52-54, fig. 3.

Freuler, Gaudenz. "Bartolo di Fredis Altar für die Annunziata-Kapelle in S. Francesco in Montalcino." Pantheon 43 (1985): 26.

Cole, Bruce. Sienese Painting in the Age of the Renaissance. Bloomington, 1985: 13, 14, fig. 8.

Boskovits, Miklós. The Martello Collection: Paintings, Drawings and Miniatures from the XIVth to the XVIIIth Centuries. Florence, 1985: 128.

1986

Leoncini, Giovanni. "Fei, Paolo di Giovanni." In La Pittura in Italia. Il Duecento e il Trecento. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo. 2 vols. Milan,1986: 2:570, repro.

1987

Christiansen, Keith. "The S. Vittorio Altarpiece in Siena Cathedral." The Art Bulletin 69 (1987): 467.

Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence B. Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York, 1987: 38.

1988

Maginnis, Hayden B. J. "The Lost Facade Frescoes from Siena’s Ospedale di S. Maria della Scala." Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 51 (1988): 190.

1991

Manacorda, Simona. "Fei, Paolo di Giovanni." In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Edited by Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana. 12 vols. Rome, 1991-2002: 6(1995):133.

1992

Landi, Alfonso, and Enzo Carli (commentary). “Racconto” del Duomo di Siena (1655). Florence, 1992: 120-121, n. 30.

1993

Harpring, Patricia. The Sienese Trecento Painter Bartolo di Fredi. London and Toronto, 1993: repro. 112.

Cséfalvay, Pál, ed. Keresztény Múzeum (Christian Museum Esztergom). Budapest, 1993: 222.

Gagliardi, Jacques. La conquête de la peinture: L’Europe des ateliers du XIIIe au XVe siècle. Paris, 1993: 106.

1994

Freuler, Gaudenz. Bartolo di Fredi Cini: ein Beitrag zur sienesischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Disentis, 1994: 341, 382.

1996

Freuler, Gaudenz. "Bartolo di Fredi Cini." In The Dictionary of Art. Edited by Jane Turner. 34 vols. New York and London, 1996: 7:329.

Gold Backs: 1250-1480. Exh. cat. Matthiesen Fine Art, London. Turin, 1996: 116, fig. 3.

1997

Chelazzi Dini, Giulietta, Alessandro Angelini, and Bernardina Sani. Sienese Painting From Duccio to the Birth of the Baroque. New York, 1997:198, 200-201.

Chelazzi Dini, Giulietta. "La cosidetta crisi della metà del Trecento (1348-1390)." In Pittura senese. Edited by Giulietta Chelazzi Dini, Alessandro Angelini and Bernardina Sani. 1st ed. Milan, 1997: 200.

1998

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Prague, 1998: 70, 98, 358, 379, 428.

1999

Norman, Diana. Siena and the Virgin: Art and Politics in a Late Medieval City State. New Haven and London, 1999: 225, nos. 28, 43.

2000

Kirsh, Andrea, and Rustin S. Levenson. Seeing Through Paintings: Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies. Materials and Meaning in the Fine Arts 1. New Haven, 2000: 88, 90-91, figs. 89-90, color fig. 91.

2002

Tomei, Alessandro, ed. Le Biccherne di Siena: arte e finanza all’alba dell’economia moderna. Exh. cat. Palazzo del Quirinale, Rome. Azzano San Paolo [u.a.], 2002: 174.

2003

Norman, Diana. Painting in Late Medieval and Renaissance Siena (1260-1555). New Haven and London, 2003: 143 (repro.), 145.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 12, no. 7, color repro.

Hiller von Gaertringen, Rudolf. Italienische Gemälde im Städel 1300-1550: Toskana und Umbrien. Kataloge der Gemälde im Städelschen Kunstinstitut Frankfurt am Main. Mainz, 2004: 140, 149, 151.

2005

Bagnoli, Alessandro, Silvia Colucci, and Veronica Radon, eds. Il Crocifisso con i dolenti in umiltà di Paolo di Giovanni Fei: un capolavoro riscoperto. Exh. cat. Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, 2005: 11, 12, 32, 34 nos. 18 and 21, 49, 51, 53, 60, 62.

2006

Butzek, Monica. “Chronologie.” In Die Kirchen von Siena, 3: Der Dom S. Maria Assunta, 1: Architektur, pt. 1. Edited by Walter Haas and Dethard von Winterfeld. Munich, 2006: 102, 103 n. 1347.

2008

Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, 2008: 81, 84, 90.

Fattorini, Gabriele. "Paolo di Giovanni Fei: una proposta per la pala Mannelli (con una nota sull’iconografia di San Maurizio a Siena)." Prospettiva 130/131 (2008): 176, 182 n. 40.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 104-111, color repro.

Wikidata ID

Q20173319