Portrait of a Lady with a Ruff

1638

Michiel van Miereveld

Artist, Dutch, 1567 - 1641

Michiel van Miereveld (also spelled Mierevelt) was trained as a history painter but quickly became one of Holland’s leading portraitists. His work was so popular at the Prince of Orange’s court in The Hague and among the elite of Dutch society that Van Miereveld became one of Delft’s richest burghers. Students and followers made numerous repetitions and variations of his compositions. Throughout his long artistic career, Van Miereveld continued to paint his human subjects in a formal and formulaic style. In his portraits, whether full or half length, he excelled in careful descriptions of external features and costume details.

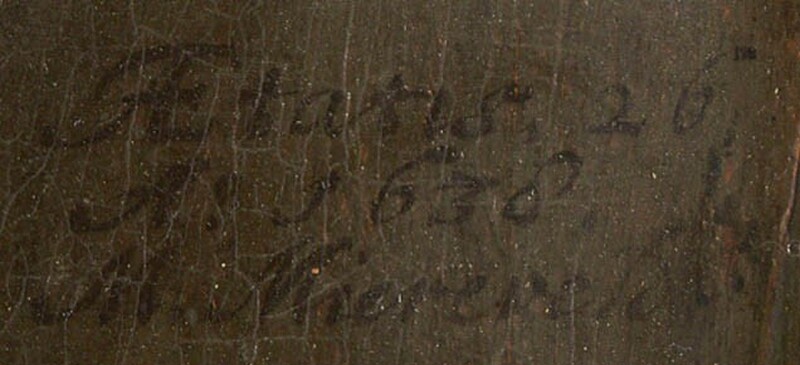

By the time he painted Portrait of a Lady with a Ruff in 1638, Van Miereveld was too set in his ways to adjust his style to the livelier approach being developed by his younger colleagues, among them Frans Hals and Rembrandt van Rijn. His continuing popularity, however, proved that he had no reason to do so. This portrait has a quiet charm, and the woman’s gentle gaze conveys a pleasant personality and an inward strength that reflects the stoic beliefs of the time. Her costume and elaborate lace-edged ruff are the epitome of craftsmanship and refinement. The embroidery on her stomacher, with its intricate pattern of flowers and birds, may contain an allegorical message that we can no longer decipher. An inscription on the painting indicates that the woman was twenty-six years old when Van Miereveld painted her. Given her age and the sumptuous dress and jewelry she wears, this could be a wedding portrait, although it is not known whether this portrait had a male pendant.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 70.5 × 57.9 cm (27 3/4 × 22 13/16 in.)

framed: 97.8 x 83.8 x 12.7 cm (38 1/2 x 33 x 5 in.) -

Accession Number

1961.5.4

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Possibly Van der Bogaerde collection, 's-Hertogenbosch.[1] possibly L. Baron, Paris; possibly (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 23 November 1901, no. 142); Pollard.[2] Mr. J.C. Bennett; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 20 December 1902, no. 80); (P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., Ltd.).[3] (Eugene Fischof, Paris); purchased 1903 by Clement Acton Griscom [1841-1912], Philadelphia;[4] (his sale, Plaza Art Galleries, New York, 26-27 February 1914, no. 11);[5] William Robertson Coe [1869-1955], Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York; Coe Foundation, New York; gift 1961 to NGA.

[1] This early provenance information was cited in the 1914 auction catalogue for the Griscom Collection.

[2] Lynda McLeod, Librarian, Christie's Archives, London, kindly provided the names of the consignor and buyer at the 1901 sale; see her e-mail of 1 August 2012, in NGA curatorial files. There is no size information in the sale catalogue, and the description is very brief, so it is not certain this is the same painting.

[3] A note in NGA curatorial files indicates that Colnaghi purchased the painting that was no. 80 in the 1902 sale. This was kindly confirmed by Lynda McLeod, Librarian, Christie's Archives, London, who also provided the name of the consignor; see her e-mail of 28 March 2013, in NGA curatorial files.

[4] The 1903 purchase date is in the 1914 sale catalogue.

[5] An annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the NGA library records the buyer as an anonymous bidder. W.R. Coe’s letter of 12 May 1942 to David Finley (copy in NGA curatorial files) confirms Coe’s purchase at the 1914 sale.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1961

Extended loan for use by Ambassador David K.E. Bruce, U.S. Embassy residence, London, England, 1961-1969.

1978

Extended loan for use by the Ambassador, U.S. Embassy residence, London, England, 1978-2011.

Bibliography

1914

Levy, Florence N., ed. American Art Annual 11. New York, 1914: 497.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 90.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 79, repro.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 232-233, repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 268, repro.

1989

Slive, Seymour. Frans Hals. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Royal Academy of Arts, London; Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem. London, 1989: 45-60.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 169-170, repro. 171.

Inscriptions

center right: AEtatis, 26 / Ao 1638 / M. Miereveldt

Wikidata ID

Q20177160