River Landscape with Ferry

1649

Salomon van Ruysdael

Painter, Dutch, c. 1602 - 1670

Salomon van Ruysdael’s masterful River Landscape with Ferry has a visual force that reflects the sense of pride the Dutch felt at the time of the signing of the Treaty of Münster in 1648, which gave full autonomy to the Dutch Republic. After war of independence from Spanish rule that lasted eighty years, the Dutch set out to explore the myriad visual delights of the prosperous country that they could finally claim as their own. Many went east, along the Rhine River, to see historic cities such as Nijmegen and Rhenen that had played significant roles in the formation of the Republic. Ruysdael may have traveled along these same routes, but no drawings from his hand survive to document any such journey. The large crenulated castle in this painting is a fanciful construct, but it is reminiscent of fortresslike structures situated along the Rhine in the eastern region of the Netherlands.

Ruysdael painted River Landscape with Ferry in 1649 when the full scope of his artistic personality had come to maturity. The work is imposing in scale and visually compelling, both for its harmonious composition and for the rich variety of its pictorial elements. It has wonderful atmospheric qualities, subtle reflections in the water, and delightful figures crowded into the ferryboat. The large clump of trees centers the composition and provides a sturdy framework for the animals and humans activating the scene. Ruysdael also effectively used these trees to open the sense of space, for not only does the ferryboat pass before them, but wagons loaded with passengers also travel the track behind them.

With the outbreak of World War II in the Netherlands, art dealer Jacques Goudstikker fled Amsterdam with his wife and son in May 1940, but he died in an accident on board the ship carrying him and his family to safety. He left behind most of his gallery's stock of paintings, and the Goudstikker collection, including this work by Ruysdael, was confiscated by the Nazis and delivered to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring later that year. The Allied forces recovered the painting at the end of the war, and it was returned to the State of the Netherlands in 1948. The painting was on view in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, from 1960 until 2006, at which time the heirs of Jacques Goudstikker reclaimed the collection from the Dutch government and received the restituted paintings. The National Gallery of Art acquired River Landscape with Ferry when a number of Goudstikker paintings subsequently reentered the art market.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 49

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 101.5 x 134.8 cm (39 15/16 x 53 1/16 in.)

-

Accession Number

2007.116.1

More About this Artwork

Video: Two-Minute Tour: Clouds, Ice, and Bounty

Join exhibition curator Betsy Wieseman on a two-minute tour of the 2021-2022 exhibition Clouds, Ice, and Bounty.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Possibly Major Hugh Edward Wilbraham, M.B.E. [1857-1930], Delamere House, near Northwich, Cheshire; by inheritance to his son, George Hugh de Vernon Wilbraham [1890-1962], Delamere House; (his sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 18 July 1930, no. 33); (Jacques Goudstikker, Amsterdam);[1] restituted 6 February 2006 to his daughter-in-law, Marei von Saher, Greenwich, Connecticut; purchased 5 November 2007 through (Christie's, New York) by NGA.

[1] The dealer Jacques Goudstikker fled Amsterdam with his wife and son in May 1940, and died in an accident on board the ship on which he left. He left behind most of his gallery's stock of paintings, including the Ruysdael, and with the rest of the Goudstikker paintings, it was confiscated by the Nazis later the same year and delivered to Hermann Göring; see Rapport inzake de Kunsthandel v.h J Goudstikker NV in oprichtung per 13 September 1940, Bijlage III, "Staat van Schilderijen, gekocht door den

Rijksveldmaarschalk H. Göring van de "oude" Goudstikker,” Access no. 1341, inv. 103, Gemeentearchief, Amsterdam. The painting was recovered by the Allies at the end of World War II and held at the Munich Central Collecting Point (where it was no. 5324), before being returned to the Netherlands in 1948. In the Netherlands, ownership was transferred among several museums, during which time the painting maintained the identifying inventory number NK 2347: Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit, The Hague, in 1948; Dienst voor's Rijks Verspreide Kunstvoorwerpen, The Hague, 1948-1975; Dienst Verspreide Rijkscollecties, The Hague, 1975-1985; Rijksdienst Beeldende Kunst, The Hague, 1985-1997; and Instituut Collectie Nederland, Amsterdam, in 1997. Physical custody of the painting was transferred in 1960 to the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, where it had the inventory number SK A 3983 and where it remained until 2006. In 2005, the Dutch Advisory Committee on the Assessment of Restitution Applications for Items of Cultural Value and the Second World War recommended in favor of the Goudstikker family's claim for the return of this and other paintings that had been confiscated in 1940. The surviving heirs were Marei von Saher, the widow of Goudstikker's son, Edward, and her daughters, Charlène and Chantel, who received the restituted paintings in early 2006.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1930

Nouvelles Acquisitions de la Collection Goudstikker, Kunsthandel J. Goudstikker, Amsterdam; Kunstkring, Rotterdam, 1930-1931, no. 65, repro.

1935

Cinq siècles d'art, Exposition Universelle et Internationale, Brussels, 1935, no. 767, under Paintings, as Le bac.

1936

Tentoonstelling van Schilderijen en Antiquiteiten, Kunsthandel J. Goudstikker N.V., Rotterdamschen Kunstkring, December 1936-January 1937, no. 57, repro., as De Veerpont.

Tentoonstelling van Werken door Salomon van Ruysdael, Kunsthandel J. Goudstikker N.V., Amsterdam, January-February 1936, no. 34, as De Veerpont.

Tentoonstelling van Oude Kunst uit het bezit van den Internationalen Handel, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1936, no. 142, repro., as De Veerpont.

Tentoonstelling van Oude Kunst, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, April 1936, no. 34, under Paintings, as De Veerpont.

1937

Dutch Paintings, Etchings, Drawings, Delftware of the Seventeenth Century, John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1937, no. 65, repro., as The Ferry Boat.

1946

Paintings Looted from Holland Returned through the Efforts of The United States Armed Forces, multi-venue tour in the United States and Canada, 1946-1948, nos. 36 and 39 (two editions of catalogue), as A Ferry.

Herwonnen Kunstbezit, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague, 1946, no. 55.

1953

Holländer des 17. Jahrhunderts, Kunsthaus Zürich, 1953, no. 134, as Landschaft mit Fähre.

1954

Dutch Painting: The Golden Age. An Exhibition of Dutch Pictures of the Seventeenth Century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art; Art Gallery of Toronto, 1954-1955, no. 73, repro., as The Ferry Boat.

Mostra di Pittura Olandese del Seicento, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome; Palazzo Reale, Milan, January-April 1954, no. 133 (Rome catalogue), no. 136 (Milan catalogue).

2008

Reclaimed: Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker, Bruce Museum of Arts and Science, Greenwich, Connecticut; The Jewish Museum, New York; The Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, and other United States venues, 2008-2010, no. 22, repro. (shown only in Greenwich, New York, and San Antonio).

2018

Water, Wind, and Waves: Marine Paintings from the Dutch Golden Age, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2018, unnumbered brochure.

2021

Clouds, Ice, and Bounty: The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund Collection of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2021, no. 6, repro.

Bibliography

1936

Hennus, M. F. "Tentoonstellingen: Amsterdam: ...Salomon van Ruysdael bij Goudstikker." _Maandblad voor Beeldende Kunsten _ 58 (1936): 58.

Heppner, A. "Salomon van Ruysdael: Spezialausstellung bei Goudstikker in Amsterdam." Internationale Kunstwelt (February 1936): 32, ill. 2.

Heppner, Arnold. Internationale Kunstwelt 1936): 32, ill. 2.

1938

Stechow, Wolfgang. Salomon van Ruysdael, eine Einführung in seine Kunst. Berlin, 1938: 124, no. 358, pl. 24, no. 33

1952

Gerson, Horst. De Nederlandse Schilderkunst, vol. 2: Het tijdperk van Rembrandt en Vermeer. De Schoonheid van Ons Land, 11. Amsterdam, 1952: 44, fig. 122.

1959

Podestà, Atillio. Pittura oladese del Seicento. Bergamo, 1959: 84, repro.

1962

Meijer, Emile R. "Salomon Jacobszoon van Ruysdael (kort na 1600-1670) 'Rivierlandschap met veerpont'." Kunstschrift Openbaar Kunstbezit 6 (1962): 35a-35b, repro.

1975

Stechow, Wolfgang. Salomon van Ruysdael: eine Einführung in seine Kunst: mit kritischem Katalog der Gemälde. Revised 2nd ed. Berlin, 1975: 123, no. 358, pl. 24, fig. 33.

1976

Thiel, Pieter J. J. van, et al. All the Paintings of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam: a completely illustrated catalogue. Translated by Gary Schwartz and Marianne Buikstra-de Boer. Maarssen, 1976: 489, no. A3983, repro.

2008

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. "Salomon van Ruysdael, River Landscape with Ferry." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 39 (Fall 2008): 28-29, repro.

Sutton, Peter C. Reclaimed: paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker. Exh. cat. Bruce Museum of Arts and Science, Greenwich, Connecticut; The Jewish Museum, New York. Greenwich and New Haven, 2008: 176-179, no. 22.

2014

Wheelock, Arthur K, Jr. "The Evolution of the Dutch Painting Collection." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 50 (Spring 2014): 2-19, repro.

2015

"Art for the Nation: The Story of the Patrons' Permanent Fund." National Gallery of Art Bulletin, no. 53 (Fall 2015): 29, repro.

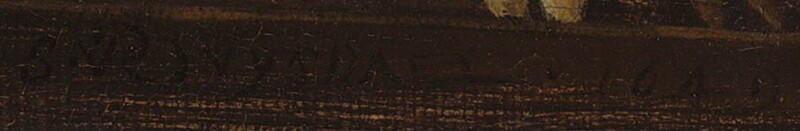

Inscriptions

on the ferry below the white horse: Salomon v. Ruysdael. 1649

Wikidata ID

Q20177276