Forest Scene

c. 1655

Jacob van Ruisdael

Artist, Dutch, c. 1628/1629 - 1682

Jacob van Ruisdael represents the pinnacle of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painting. This great artist, the son of a painter and the nephew of Salomon van Ruysdael (see NGA 2007.116.1), began his career in Haarlem but moved to Amsterdam in about 1656. His long and productive career yielded a wide variety of landscape scenes that reflect Ruisdael’s vision of the grandeur and powerful forces of nature.

His most characteristic paintings include massive trees that tower above a rocky countryside, in which human figures seem dwarfed by the elements of nature. The scale and solemn dignity of Forest Scene make it one of Ruisdael’s masterpieces. The man and woman walking along a path near some grazing sheep in the middle distance are insignificant in comparison to the broad waterfall, the massive rocks, and the huge fallen birch tree in the foreground. The somber mood is reinforced by ominous clouds and by the dark green of the grass and foliage. Trees with twisted roots survive precariously on rocky outcroppings. The broken trees in the foreground are important not only as compositional devices but also as symbolic reminders of the transience of life and the inevitability of death.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 105.5 x 123.4 cm (41 9/16 x 48 9/16 in.)

-

Accession Number

1942.9.80

More About this Artwork

Article: Portraits of Trees, a Favorite Subject of Artists

Many artists have painted, photographed, and drawn nature’s magnificent sculptures.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Probably owned by Francis Nathaniel, 2nd marquess Conyngham [1797-1876], Mount Charles, County Donegal, and Minster Abbey, Kent.[1] Sir Hugh Hume-Campbell, 7th bart. [1812-1894], Marchmont House, Borders, Scotland, by 1857;[2] (his estate sale, Christie, Manson, & Woods, London, 16 June 1894, no. 48); (P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London); sold 1894 to Peter A.B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; gift 1942 to NGA.

[1] The only source of information concerning the picture's whereabouts prior to 1857 is Hofstede de Groot, whose listing of the painting is extremely confusing (Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century, trans. Edward G. Hawke, 8 vols., London, 1907-1927: 4(1912):92, no. 285, possibly also 119, no. 367, 134, no. 418, 203, no. 643c). It seems that any or all of his four entries (nos. 285, 367, 418, and 643c) may contain information that relates to the Forest Scene, but these entries also contain additional and contradictory provenance listings, which must refer to at least one other painting. It nonetheless seems likely that before the Forest Scene was acquired by Sir Hugh Hume Campbell, it was indeed owned by a member of the Conyngham family of Ireland, most probably the 2nd marquess, but also possibly his father, Henry, 3rd baron and 1st marquess Conyngham (1766-1832).

[2] Gustav Friedrich Waagen, _Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures and Illuminated Mss., 3 vols., London, 1854-1857, supplement: 441-442.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1866

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom, London, 1866, no. 59 (possibly also 1855, no. 54, and 1857, no. 9).[1]

1877

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1877, no. 199.

Bibliography

1854

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated Mss.. 3 vols. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. London, 1854: supplement 441.

1855

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of pictures by Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, French and English masters with which the proprietors have favoured the Institution. Exh. cat. British Institution. London, 1855: possibly no. 54, as Landscape.

1857

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Galleries and Cabinets of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of more than Forty Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Mss., &c.&c., visited in 1854 and 1856, ..., forming a supplemental volume to the "Treasures of Art in Great Britain." London, 1857: 441.

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of pictures by Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, French and English masters with which the proprietors have favoured the Institution. Exh. cat. British Institution. London, 1857: possibly no. 9, as Landscape and Figures.

1866

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of pictures by Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, Franch, and English masters. Exh. cat. British Institution. London, 1866: no. 59, as Rocky Landscape with Waterfall.

1877

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1877: no. 199.

1885

Catalogue of Paintings Forming the Collection of P.A.B. Widener, Ashbourne, near Philadelphia. 2 vols. Paris, 1885-1900: 2(1900):274.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 4(1911):87, no. 285 (possibly also 111, no. 367, 125, no. 418, 192, no. 643c).

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 4(1912):92, no. 285 (possibly also 119, no. 367, 134, no. 418, 203, no. 643c).

1913

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis, and Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Pictures in the collection of P. A. B. Widener at Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Early German, Dutch & Flemish Schools. Philadelphia, 1913: unpaginated, repro.

1923

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro.

1928

Rosenberg, Jakob. Jacob van Ruisdael. Berlin, 1928: 87, no. 241.

1930

Simon, Kurt Erich. Jacob van Ruisdael: eine Darstellung seiner Entwicklung. Berlin, 1930: 62, pl. 8.

1931

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 94, repro.

1935

Tietze, Hans. Meisterwerke europäischer Malerei in Amerika. Vienna, 1935: 338, no. 192.

1939

Tietze, Hans. Masterpieces of European Painting in America. New York, 1939: no. 192.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Works of art from the Widener collection. Washington, 1942: 6.

1948

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948: 58, repro.

1952

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds., Great Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1952: 108, color repro.

1957

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Comparisons in Art: A Companion to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. London, 1957 (reprinted 1959): pl. 143.

1959

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Reprint. Washington, DC, 1959: 58, repro.

1960

Baird, Thomas P. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art 7. Washington, 1960: 18, color repro.

The National Gallery of Art and Its Collections. Foreword by Perry B. Cott and notes by Otto Stelzer. National Gallery of Art, Washington (undated, 1960s): 25.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 194-195, no. 676, repro.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 119.

1966

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1: 252, color repro.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 106, repro.

Gandolfo, Giampaolo et al. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Great Museums of the World. New York, 1968: 140, color repro.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 316, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 292-293, no. 391, color repro.

1979

Watson, Ross. The National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1979: 77, pl. 64.

1981

Schmidt, Winfried. Studien zur Landschaftskunst Jacob van Ruisdaels: Frühwerke und Wanderjahre. Hildesheim, 1981: 90.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 292, no. 384, color repro.

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1984: 36-37, color repro.

Britsch, Ralph A., and Todd A. Britsch. The arts in Western culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1984: 258, fig. 11-16.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 363, repro.

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 305.

1991

Walford, E. John. Jacob van Ruisdael and the Perception of Landscape. New Haven, 1991: 102-104, 117, 144, repro.

1992

National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1992: 136, color repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 339-343, color repro. 341.

Katz, Elizabeth L., E. Louis Lankford, and Janice D. Plank. Themes and foundations of art. Minneapolis, 1995: 452, fig. 8-101.

2001

Slive, Seymour. Jacob van Ruisdael: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Drawings and Etchings. New Haven, 2001: 243-244, no. 295.

2002

Hunt, John Dixon. The picturesque garden in Europe. New York, 2002: 17, fig. 13.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 204-205, no. 162, color repro.

Allen, Eva J. A Vision of Nature: The Landscapes of Philip Koch: Retrospective, 1971-2004. Exh. cat. University of Maryland University College, Adelphi, 2004: 14-15, fig. 6.

2005

Slive, Seymour. Jacob van Ruisdael: Master of Landscape. Exh. cat. Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Royal Academy of Arts, London. London, 2005: no. 32, 108, 109 repro.

2006

Schwartz, Sanford. "White Secrets." New York Review of Books (February 9, 2006): 8.

2012

Tummers, Anna. The Eye of the Connoisseur: Authenticating Paintings by Rembrandt and His Contemporaries. Amsterdam, 2012: 101, color fig. 46.

2020

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Clouds, ice, and Bounty: The Lee and Juliet Folger Collection of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2020: 21, 132, fig. 1, 133.

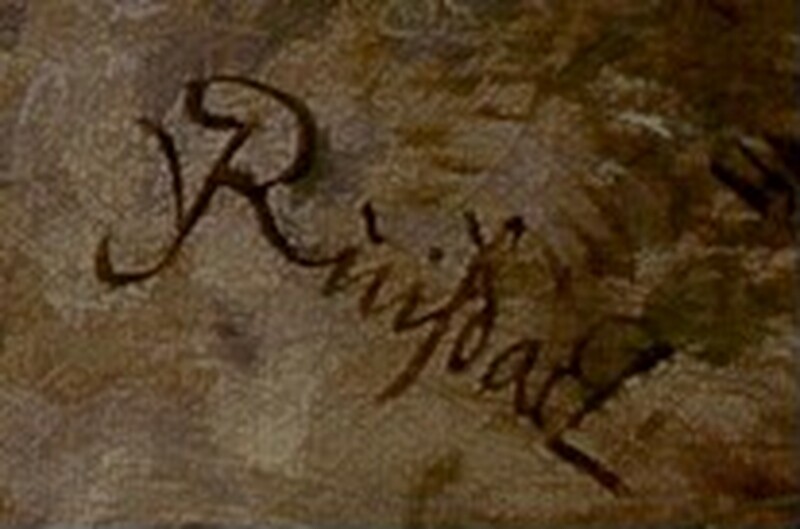

Inscriptions

lower right: J v Ruisdael (JvR in ligature)

Wikidata ID

Q20177382