Battle Scene

c. 1645/1646

Philips Wouwerman

Painter, Dutch, 1619 - 1668

Philips Wouwerman, an important Haarlem painter from the mid-seventeenth century, is best known for his elegant hunting scenes. In his early career, however, he specialized in boldly expressive depictions of military encounters. Wouwerman’s dynamic vision of men and horses in the midst of battle seems to have been inspired by non-Dutch pictorial sources, which he would have known primarily through prints. Chief among these was Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630), whose etchings of battle scenes featuring rearing horses and close combat were widely circulated and enormously influential during the early seventeenth century. The dramatic poses of men and horses recall the oeuvre of Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), but one can also recognize the influence of the Italianate painter Pieter van Laer (1599–1642), whose sketchbook Wouwerman owned.

Images of warfare had a long tradition in Netherlandish painting, from sixteenth-century representations of peasant revolts to the various combat scenes that were popular during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). For Wouwerman, this long-drawn-out and devastating war may have become a particularly topical subject following his short period of study in northern Germany in 1638–1639, where he may have witnessed or heard firsthand accounts of the armed conflicts in that country.

In this powerful work from about 1645/1646, the viewer is presented with a violent skirmish between Dutch and Spanish soldiers. As the fierce confrontation rages on, dead bodies lie strewn on the ground and a maimed drummer tries to flee from the mayhem. Instead of extolling the heroism of military exploits, Wouwerman bears witness to a brutal display of human violence and the suffering that results. For all of the cold realism of the subject matter, Wouwerman painted this scene with a remarkably subtle palette and close attention to detail. Every element is carefully integrated into a dynamic composition that displays his considerable artistic skill at perspective and lifelike representation of bodies in motion.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 47

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

Gift of Joseph F. McCrindle in memory of Frederick A. den Broeder

-

Dimensions

overall: 48 x 82.5 cm (18 7/8 x 32 1/2 in.)

framed: 62.9 x 97.3 x 6 cm (24 3/4 x 38 5/16 x 2 3/8 in.) -

Accession Number

2000.159.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Carlo Sestieri, Rome);[1] purchased 1960s by Joseph F. McCrindle [1923-2008], New York; gift 2000 to NGA.

[1] Although the earlier provenance of the painting is not known, hints of its history exist in earlier sale records and from labels on the verso of the panel. This work may be the painting identified as “Cavalry fight on a Hill” that was sold by J. H. van Heemskerk in The Hague in 1770 (sale of 29 March 1770, no. 142, sold for 461 florins to Deodati). The dimensions recorded for that work, 20 1/2 by 34 1/2 inches, are only slightly larger than those of this painting. See: Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century, translated by Edward G. Hawke, 8 vols., London, 1907-1927: 2(1909):498, no. 770e. One of the old handwritten labels on the verso reads: “N:XXVII / Une bataille par Phillippe Wouwerman.” The other label, which indicates that the painting was at one point in Sweden, reads: “Österby-samlinger / Söderfors.”

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1983

Haarlem: The Seventeenth Century, The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1983, no. 137, repro.

1997

In Celebration: Works of Art from the Collections of Princeton Alumni and Friends of the Art Museum, Princeton University, The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1997, no. 166, repro.

Bibliography

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: possibly 2(1909):498, no. 770e.

1983

Hofrichter, Frima Fox. Haarlem: The Seventeenth Century. New Brunswick, 1983: 144.

1993

Duparc, Frederik J. "Philips Wouwerman, 1619 - 1668." Oud Holland 107, no. 3 (1993): 265, 285 n. 92.

1997

Guthrie, Jill. In celebration: works of art from the collections of Princeton alumni and friends of the Art Museum, Princeton University. Exh. cat. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, 1997: 131, no. 166.

2007

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr., and Michael Swicklik. "Behind the Veil: Restoration of a Dutch Marine Painting Offers a New Look at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and History." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 37 (Fall 2007): 4-5, fig. 7.

2012

Grasselli, Margaret M., and Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., eds. The McCrindle Gift: A Distinguished Collection of Drawings and Watercolors. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2012: 19, fig. 8, repro. 185.

Inscriptions

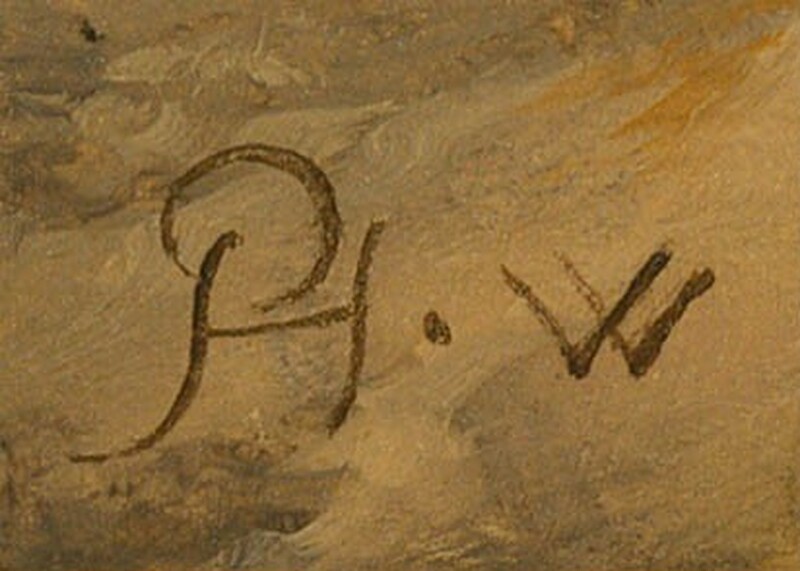

lower right, PH in monogram: PH.W.

Wikidata ID

Q20177199