The Travelers

166[2?]

Meindert Hobbema

Artist, Dutch, 1638 - 1709

Meindert Hobbema studied under the noted landscape artist Jacob van Ruisdael, and quite a few of his compositions evolved from the work of his erstwhile master. The Travelers, one of Hobbema’s largest works, is a close variant of a smaller painting of a watermill by Ruisdael now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Hobbema approached nature in a straightforward manner, depicting picturesque, rural scenery enlivened by the presence of peasants or hunters. He often reused favorite motifs such as old watermills, thatch-roofed cottages, and embanked dikes, rearranging them into new compositions. Hobbema’s rolling clouds allow patches of sunshine to illuminate the rutted roads or small streams that lead back into rustic woods. All six of the National Gallery’s canvases by Hobbema share these characteristics.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 101 x 145 cm (39 3/4 x 57 1/16 in.)

-

Accession Number

1942.9.31

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Gosen Geurt Alberda van Dyksterhuys [d. 1830], Château Dyksterhuys, Province of Groningen, by 1829; R. Gockinga and P. van Arnhem, Groningen, after 1829; (sale, Amsterdam, 5 July 1833, no. 11);[1] R. Gockinga, Groningen. Colonel Biré, Brussels;[2] (sale, Bonnefons de Lavialle, Paris, 25-26 March 1841, no. 2); William Williams Hope [1802-1855], Rushton Hall, Northamptonshire, and Paris;[3] (sale, Christie & Manson, London, 14-16 June 1849, no. 124); purchased by Fuller or perhaps bought in;[4] (William Williams Hope sale, Pouchet, Paris, 11 May 1858, no. 2). William Ward, 1st earl of Dudley [1817-1885, created earl 1860], Witley Court, Worcestershire, by 1871; by inheritance to his son, William Humble Ward, 2nd earl of Dudley [1867-1932], Witley Court; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 25 June 1892, no. 9); (P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London);[5] sold 1894 to Peter A.B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; gift 1942 to NGA.[6]

[1] Both Van Arnhem and Gockinga had individually offered to buy the two pictures by Hobbema, including NGA 1942.9.31, that Gosen Geurt Alberda van Dyksterhuys owned. Before either had closed the deal, however, the owner died. It was later arranged that the two would purchase the paintings together; see Charles J. Nieuwenhuys, A Review of the Lives and Works of Some of the Most Eminent Painters, London, 1834:147-149.

[2] The catalogue of this sale bears the title Catalogue d'une riche collection de tableaux des écoles flamande et hollandaise, recueillie par M. Héris de Bruxelles..., but although the collection was "recueillie" (collected/gathered) by Héris and was offered for sale under his name, he may not himself have been the owner of the paintings. In the copy of the sale catalogue at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the words "Recueillie par M. Héris de Bruxelles" in the title are followed by the handwritten addition, "pour M. le Colonel Biré," and alongside the title in the Victoria and Albert Museum's copy is written "mais c'est la collection de M. le Colonel Biré," which suggests that Héris may have been acting as Biré's agent in acquiring and selling the pictures.

[3] The buyer's name is noted in the Philadelphia copy of the sale catalogue as "hoppe," which is probably a misspelling of Hope. (The 1858 Hope sale catalogue states that Hope bought the picture at the Héris sale.)

[4] Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century..., 8 vols., trans. by Edward G. Hawke, London, 1907-1927: 4:406, lists the 1849 sale in the provenance of his no. 100, a painting that may or may not be identical with his no. 94, 4:403-404 (which is definitely The Travelers). The compositional descriptions given in both these Hofstede de Groot entries are similar, but the dimensions listed for no. 100, 51 x 54 inches, are impossible for the National Gallery picture. The identity and whereabouts of Hofstede de Groot no. 100 remain unclear; it is possible that Hofstede de Groot was mistaken in the dimensions that he gave for this picture, and that it was indeed the same painting as his no. 94. Hofstede de Groot further confuses the issue by listing part of the provenance of The Travelers under no. 94, and part (the 1841 Héris sale) under no. 100. The 1849 Hope sale catalogue does not give dimensions, so it is impossible to establish whether the painting offered there was The Travelers or the unknown, and perhaps apocryphal, "Hofstede de Groot 100." The picture in question fetched £367.10, and Hofstede de Groot, citing as his source a handwritten note in Smith's own copy of his Catalogue Raisonné, says that it was bought in. (In this copy, which is at the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, The Hague, Smith gives the buyer as "Fuller," but this is not necessarily contradictory, as Fuller may have been a Christie's employee.) Smith's statement is probably correct, for the National Gallery of Art's painting remained in the possession of W.W. Hope until 1858, when it was sold in Paris.

[5] Colnaghi lent the painting to the Royal Academy of Art’s 1894 Winter Exhibition, which ran from January to March. The sale to Widener must have occurred later in the year.

[6] A label from the Art Institute of Chicago shipping room, dated 27 January 1943, was removed from the painting’s stretcher in 1981, but neither the Art Institute nor the NGA registrar’s office records this movement.

Associated Names

- Alberda van Dyksterhuys, Gosen Geurt

- Arnhem, P. van

- Gockinga, R.

- Sale, Amsterdam

- Biré, Colonel

- Bonnefons de Lavialle

- Hope, William Williams

- Christie, Manson & Woods, Ltd.

- Fuller

- Pouchet

- Ward, 1st earl of Dudley, William

- Ward, William Humble, 2nd earl of Dudley

- P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., Ltd.

- Widener, Peter Arrell Brown

- Widener, Joseph E.

Exhibition History

1871

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1871, no. 369, as A Landscape: travellers passing through a wood.

1894

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1894, no. 60, as A Watermill.[1]

1997

Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch Paintings from the National Gallery of Art, The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, 1997, unnumbered brochure.

Bibliography

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 9(1842):727, no. 25.

1834

Nieuwenhuys, Charles J. A Review of the Lives and Works of Some of the Most Eminent Painters. London, 1834: 147-149.

1839

Koppius, P. A. "Meindert Hobbema." Drentsche Volksalmanak (1839): 114–128, repro., as dated 1662.

Héris, Henri. "Sur la Vie et les Ouvrages de Meindert Hobbema." La Renaissance: Chronique des Arts et de la Littérature 54 (1839): 5-7, repro.

1854

Jervis-White-Jervis, Lady Marian. Painting and Celebrated Painters, Ancient and Modern. 2 vols. London, 1854: 2:225.

1859

Thoré, Théophile E. J. (William Bürger). "Hobbema." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 4 (October 1859): 34, 36, 38.

1861

Blanc, Charles. "Minderhout Hobbema." In École hollandaise. 2 vols. Histoire des peintres de toutes les écoles 1-2. Paris, 1861: 2:10 (each artist's essay paginated separately).

1864

Scheltema, Pieter. "Meindert Hobbema: Quelques Renseignements sur ses Oeuvres et sa Vie." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 16 (March 1864): 219 n. 3.

1885

Catalogue of Paintings Forming the Collection of P.A.B. Widener, Ashbourne, near Philadelphia. 2 vols. Paris, 1885-1900: 2(1900):no. 212, repro.

1891

Cundall, Frank. The Landscape and Pastoral Painters of Holland: Ruisdael, Hobbema, Cuijp, Potter. Illustrated biographies of the great artists. London, 1891: 157.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 4(1912):385-386, no. 94, 387-388, no. 100.

1913

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis, and Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Pictures in the collection of P. A. B. Widener at Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Early German, Dutch & Flemish Schools. Philadelphia, 1913: unpaginated, repro.

1923

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro.

1927

Rosenberg, Jakob. "Hobbema." Jahrbuch der Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 48, no. 3 (1927): 139-151.

1931

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 78, repro.

1937

Roos, Frank J., Jr. An Illustrated Handbook of Art History. New York, 1937: 183, repro.

1938

Broulhiet, Georges. Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709). Paris, 1938: 71, 381, no. 32, repro., as after Ruisdael, dated 1664.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Works of art from the Widener collection. Washington, 1942: 5.

1948

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948 (reprinted 1959): 59, repro.

1959

Stechow, Wolfgang. "The Early Years of Hobbema." Art Quarterly 22 (Spring 1959): 3-18.

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Reprint. Washington, DC, 1959: 59, repro.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 68.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 60, repro.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 176, repro.

1981

Schmidt, Winfried. Studien zur Landschaftskunst Jacob van Ruisdaels: Frühwerke und Wanderjahre. Hildesheim, 1981: 156, 198 n.192.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 203, repro.

1987

Sutton, Peter C. Masters of 17th-century Dutch landscape painting. Exh. cat. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Philadelphia Museum of Art. Boston, 1987: 350.

Formsma, Wiebe Jannes, R. A. Luitjens-Dijkveld Stol, and A. Pathuis. De Ommelander Borgen en Steenhuizen. Groninger Historische Reeks 2. 2nd revised ed. Assen, 1987: 35-37, 330-337.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 113-117, color repro. 115.

1997

Chrysler Museum of Art. Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch paintings from the National Gallery of Art. Exh. brochure. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk. Washington, 1997: unnumbered repro.

2011

Slive, Seymour. Jacob van Ruisdael: Windmills and Water Mills. Los Angeles, 2011: 87, 89 fig. 63, 101 n. 71.

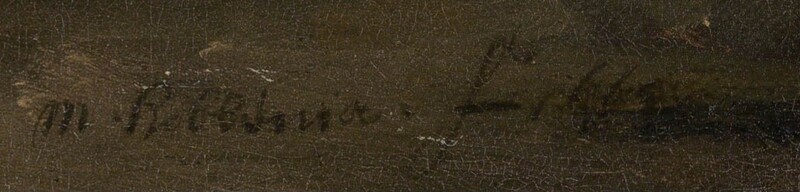

Inscriptions

lower right: m .hobbema . f 166[2?]

Wikidata ID

Q20177580