Portrait of a Man

1648/1650

Frans Hals

Artist, Dutch, c. 1582/1583 - 1666

Frans Hals was the preeminent portrait painter in Haarlem, the most important artistic center of Holland in the early part of the seventeenth century. He was famous for his uncanny ability to portray his subjects with relatively few bold brushstrokes, and often used informal poses to enliven his portraits.

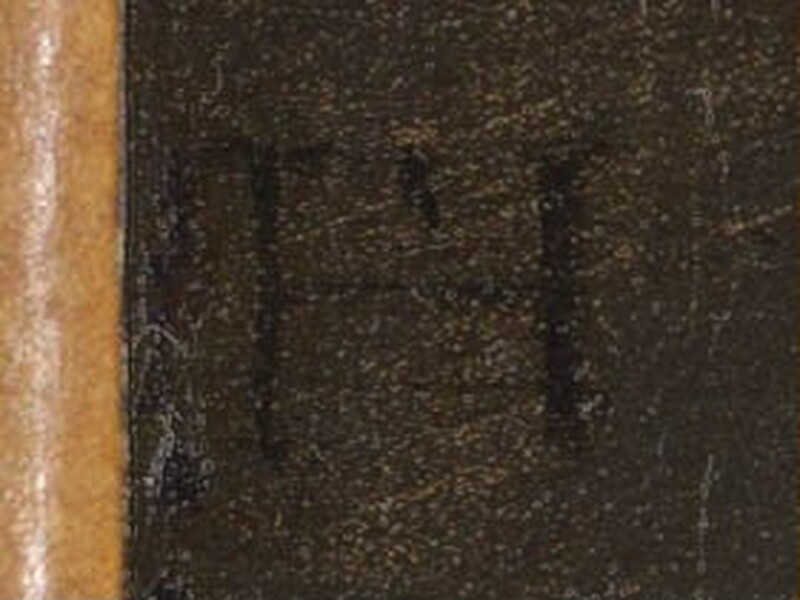

This portrait of an unknown sitter bears Frans Hals’ monogram FH in the lower left. The sitter may have been a fellow artist: with his right hand covering the area of the heart, the man not only conveys his sincerity and passion but also proclaims his artistic sensibility.

The fluid brushstrokes defining individual strands of hair are consistent with Hals’ work from the end of the 1640s, a period in which hats with cylindrical crowns and upturned brims, such as the one shown here, were fashionable. Interestingly, this man’s hair was extended and the hat painted out sometime before 1673. In 1990–1991 National Gallery of Art conservators removed the overpaint of prior treatments that had lengthened the hair and hidden the hat, thereby restoring the portrait’s original appearance.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 46

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 63.5 x 53.5 cm (25 x 21 1/16 in.)

framed: 92.4 x 81.3 x 9.2 cm (36 3/8 x 32 x 3 5/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1942.9.28

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Remi van Haanen [1812-1894], Vienna, by 1873.[1] (Mssrs. Lawrie & Co., London, by March 1898);[2] (Bourgeois Frères, Paris), in 1898; (Leo Nardus [1868-1955], Suresnes, France, and New York); sold 1898 to Peter A.B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania;[3] inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park; gift 1942 to NGA.

[1] Remi van Haanen was a Dutch painter who was active in Vienna after he moved to Austria in 1837. He lent the painting to an exhibition in Vienna in 1873. The painting is also cited as being owned by Van Haanen by Wilhelm von Bode, Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei, Braunschweig, 1883: 89.

[2] Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century..., 8 vols., trans. and ed. by Edward G. Hawke, London, 1907-1927, 3(1910): 89, no. 311.

[3] The 1898 date for Bourgeois and Nardus is according to notes by Edith Standen, Widener’s secretary for art, in NGA curatorial files. Stephen Bourgeois of Bourgeois Frères was Nardus’ father-in-law. The Widener files and Catalogue of Paintings Forming the Collection of P. A.B. Widener, Ashbourne, near Philadelphia, 2 vols., Paris, 1885–1900: 2:207, list the previous owner as Roo van Westmaas, Woortman, Holland, but no supporting evidence has been found for this name, and there is no town of Woortman in the Netherlands. In fact, Hofstede de Groot (or one of his German assistants) annotated a copy of his own work on Hals with a note indicating that Nardus had provided a purely ficticious provenance for the painting: “…die in Katalog angegebene Provenienz aus Sammulungen, die nie exisistiert haben, berucht auf intümlicher von Nardus” (handwritten note, Handexemplaren Hofstede de Groot, Frans Hals #311, Rijksbureau voor kunsthistorische documentatie, The Hague; found and kindly shared with NGA by Jonathan Lopez, per his letter of 24 April 2006 and e-mail of 1 May 2006, in NGA curatorial files.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1873

Gemälde alter Meister aus dem Wiener Privatbesitze, Österreichisches Museum für Künst und Industrie, Vienna, 1873, no. 38.

1909

The Hudson-Fulton Celebration, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909, no. 32, repro.

Bibliography

1873

Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie. Gemälde alter Meister aus dem Wiener Privatbesitze. Exh. cat. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie, Vienna, 1873: 10, no. 38.

1883

Bode, Wilhelm von. Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei. Braunschweig, 1883: 89, no. 122.

1885

Catalogue of Paintings Forming the Collection of P.A.B. Widener, Ashbourne, near Philadelphia. 2 vols. Paris, 1885-1900: 2(1900):no. 207, repro.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 3(1910):89, no. 311.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 3(1910):88, no. 311.

1908

Martin, Wilhelm. "Notes on Some Pictures in American Private Collections." The Burlington Magazine 14 (October 1908): 59-60, pl. 2.

1909

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Catalogue of a collection of paintings by Dutch masters of the seventeenth century. The Hudson-Fulton Celebration 1. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1909: 33, no. 32, repro., 154, 161.

1910

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Old Dutch Masters Held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Connection with the Hudson-Fulton Celebration. New York, 1910: 128, no. 32, repro. 129.

Cox, Kenyon. "Art in America, Dutch Paintings in the Hudson-Fulton Exhibition II." The Burlington Magazine 16, no. 82 (January 1910): 245.

1913

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis, and Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Pictures in the collection of P. A. B. Widener at Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Early German, Dutch & Flemish Schools. Philadelphia, 1913: unpaginated, no. 13, repro.

1914

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Moritz Julius Binder. Frans Hals: Sein Leben und seine Werke. 2 vols. Berlin, 1914: 2:59, 191, pl. 120b.

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Moritz Julius Binder. Frans Hals: His Life and Work. 2 vols. Translated by Maurice W. Brockwell. Berlin, 1914: 2:no. 191, pl. 120b.

1921

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Frans Hals: des meisters Gemälde in 318 Abbildungen. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 28. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1921: 320, 238, repro.

1923

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro.

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Frans Hals: des Meisters Gemälde in 322 Abbildungen. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 28. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Berlin, and Leipzig, 1923: 321, 251, repro.

1930

Dülberg, Franz. Frans Hals: Ein Leben und ein Werk. Stuttgart, 1930: 198, 223.

1931

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 80, repro.

1936

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Frans Hals Paintings in America. Westport, Connecticut, 1936: no. 96, repro.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Works of art from the Widener collection. Washington, 1942: 5, no. 624.

1948

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948 (reprinted 1959): 51, repro.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 337, 311, repro.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 66.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 58, repro.

1970

Slive, Seymour. Frans Hals. 3 vols. National Gallery of Art Kress Foundation Studies in the History of European Art. London, 1970–1974: 2(1970):no. 310, repro.; 3(1974):102-103, no. 198.

1972

Grimm, Claus. Frans Hals: Entwicklung, Werkanalyse, Gesamtkatolog. Berlin, 1972: 24, 28, 107, 205, no. 137, fig. 161.

1974

Montagni, E.C. L’opera completa di Frans Hals. Classici dell’Arte. Milan, 1974: 106, no. 187, repro.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 170, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 268-269, no. 353, repro.

1976

Montagni, E.C. Tout l'oeuvre peint de Frans Hals. Translated by Simone Darses. Les classiques de l'art. Paris, 1976: no. 187, repro.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 268, no. 347, color repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 197, repro.

1989

Slive, Seymour. Frans Hals. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Royal Academy of Arts, London; Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem. London, 1989: no. 73, repro.

Grimm, Claus. Frans Hals: das Gesamtwerk. Stuttgart, 1989: 194-195, 288, no.132, repro.

1990

Grimm, Claus. Frans Hals: The Complete Work. Translated by Jürgen Riehle. New York, 1990: 194-195, 288, no. 132, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 85-88, color repro. 87.

Grassi, Marco. "Art and Alchemy." Art & Auction 17 (June 1995): 88–91; 122, repro.

2021

Quodbach, Esmée. "A forgotten episode from America's history of collecting: the rise and fall of art dealer Leo Nardus, 1894-1908." Simiolus 43, no. 4 (2021): 353-375, esp. 373 n. 79.

Inscriptions

lower left in monogram: FH

Wikidata ID

Q18032401