Doylestown House--The Stove

1917

Charles Sheeler

Artist, American, 1883 - 1965

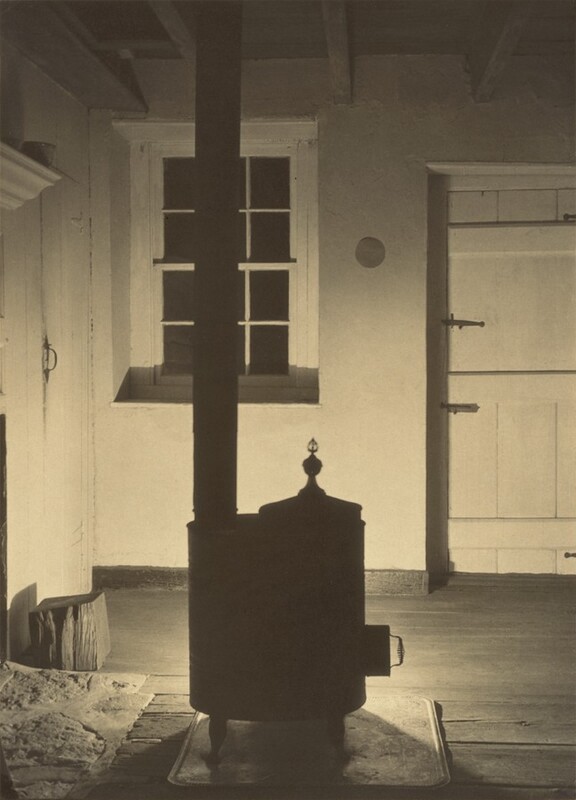

It's Sunday—but nothing can mar the beauty of this crisp Spring morning. The scene takes place in a little country house—which is filled with the merriment of a weekend party—of one—rather two—for the moment I had forgotten the stove which gives out a welcome warmth from its red opening....One of the characters (the one which is not smoking) light[s] a Benson & Hedges—The stove demands more fuel.1 Charles Sheeler to Walter Arensberg

In 1917, when he had been photographing for only a few years, Charles Sheeler embarked on one of his most important—arguably his best—series of photographs, a group of studies of a simple 18th-century house he shared with the painter Morton Schamberg in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Although Sheeler, like his roommate Schamberg, was trained as a painter at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, he learned how to photograph in 1910 in order to support himself. The copy photographs that he made for galleries and private collectors such as Walter Arensberg brought him into contact with some of the most advanced art of the period. In addition, his frequent visits to Alfred Stieglitz's gallery 291 further deepened his understanding of modern European art, while his conversations with the older photographer encouraged his growing interest in the expressive potential of photography.

Sheeler and Schamberg spent long weekends at the quiet, charming, but decrepit house in Doylestown. Although in the 1920s Sheeler would come to be associated with the depiction of American urban and industrial landscape, he clearly cherished the solitude he found in Doylestown: "The little house would be so happy to receive you," he told Stieglitz in 1917, "and I can add from experience the advantage it has proven to call a halt in the midst of the rush—go out there, put one's windows up and let the fresh air clear out the atmosphere."2 Sheeler used his time in Doylestown to great advantage, consolidating many of the lessons he had recently learned about modern European art, especially from his study of Cézanne and Picasso. Working at night and using a harsh artificial light that cast strong shadows and revealed few details, he created a series of photographs with daringly modernist compositions that emphasized the flat, formal, and geometric design of the house. Just as important, though, in these photographs (including Doylestown House—The Stove and Doylestown House—The Stairwell) Sheeler demonstrated how American artists could merge this new European vision with the distinctly American subject matter of the vernacular architecture of rural Pennsylvania.

Sheeler was particularly attached to the stove, which he called his "companion": he made two photographs of it and fifteen years later used this one (Doylestown House—The Stove) as the source for a crayon drawing, Interior with Stove. Situated in the center of our photograph, radiating "a welcome warmth," the gracefully defined 19th-century stove has obliterated the more traditional source of heat (the fireplace barely visible to the left) for this 18th-century room. Like Sheeler himself, the stove was a transplant from another era; it was a new object that had found a space and a function in an older environment. In this way, Sheeler found what his contemporary Van Wyck Brooks called "the useable past," and demonstrated how 20th-century American art and life could draw strength and sustenance from the nation's cultural history.

(Text by Sarah Greenough, published in the National Gallery of Art exhibition catalogue, Art for the Nation, 2000)

Notes

1. Letter to Walter Arensberg, [c. 1918]; quoted in Karen Lucic, Charles Sheeler in Doylestown: American Modernism and the Pennsylvania Tradition [exh. cat., Allentown Art Museum] (Allentown, 1997), 24.

2. Letter to Stieglitz, June, 13, 1917; quoted in Lucic, 19.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

gelatin silver print

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

image: 23.7 × 17 cm (9 5/16 × 6 11/16 in.)

-

Accession Number

1998.19.3

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Mrs. Saundra Lane, Lunenburg, MA; purchased with funds donated from the Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund by NGA, 1998.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1999

Photographs from the Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1999.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000-2001.

2006

Charles Sheeler: Across Media, National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, de Young, Legion of honor, San Francisco, 2006 - 2007, no. 2.

2015

In Light of the Past: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Collecting Photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 3 – July 26, 2015

Bibliography

1987

Stebbins, Theodore E., Jr., and Norman Keyes, Jr. Charles Sheeler: The Photographs. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts. Boston, 1987: pl. 11.

1997

Lucic, Karen. Charles Sheeler in Doylestown: American Modernism and the Pennsylvania Tradition. Exh. cat. Allentown Art Museum. Allentown (Pennsylvania), 1997: pl. 15.

Inscriptions

by later hand, on mount, lower left verso in graphite: L95.3.64

Wikidata ID

Q64145814